NAIROBI, Kenya (AP) – Jimmy Carter was the first U.S. president to make an official visit to sub-Saharan Africa. He once called helping Zimbabwe transition from white rule to independence “our single greatest success.” And when he died at age 100, the foundation’s work in rural Africa had come close to achieving his quest to eradicate a disease that afflicts millions of people for the first time since the eradication of smallpox. .

Africa, a fast-growing region with a population comparable to China and expected to double by 2050, is where Carter’s legacy is most evident. Until he became president, U.S. leaders showed little interest in Africa, even as independence movements swept the region in the 1960s and 1970s.

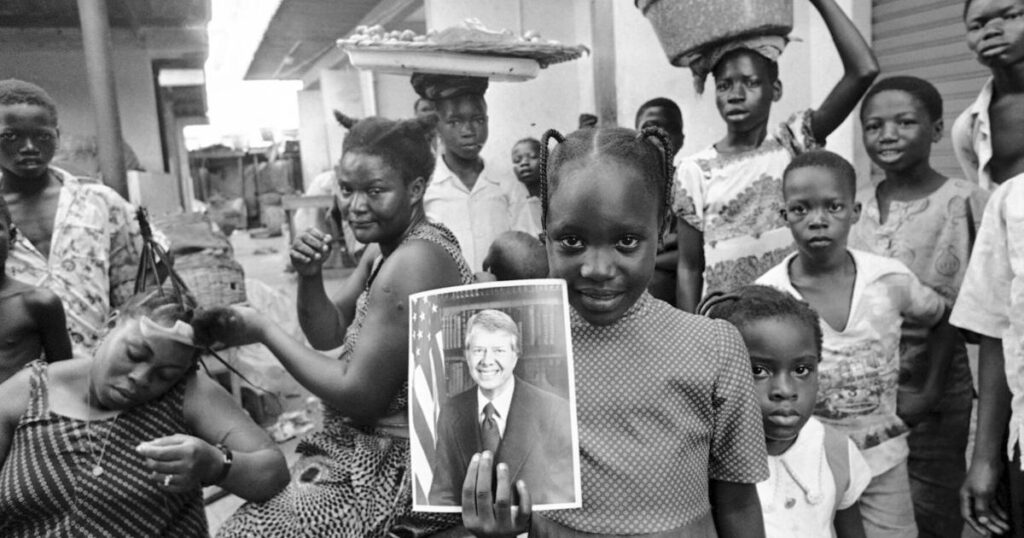

“I think the days of the so-called ugly American are over,” Carter said in 1978 during a warm welcome in Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country. He said the official state visit had erased “past aloofness by the United States” and joked that he might work on groundnut cultivation with Nigerian President Olesegun Obasanjo.

Cold War tensions turned Carter’s attention to the continent as the United States and Soviet Union competed for influence. But Carter also drew on the missionary tradition of his Baptist faith and the racial injustice he witnessed in his native southern United States.

“For too long, our country has ignored Africa,” Carter told the Democratic National Committee during his first year in office.

African leaders quickly received invitations to the White House, intrigued by the sudden interest from the world’s most powerful nation and what it meant for them.

President Kenneth Kaunda, who visited Zambia, said, “It’s a refreshing breath of fresh air.”

After his first visit to Africa, Mr. Carter said: “There is a common theme in the advice given to me by leaders of African countries: “We want to manage our own affairs. We also want to be friends with European countries. We don’t want to pick an advantageous position.”

This theme continues today as China competes with Russia and the United States for influence and access to African raw materials. But neither superpower had an envoy like Mr. Carter. Mr. Carter put human rights at the center of U.S. foreign policy and traveled to Africa 43 more times after taking office, promoting Carter Center projects aimed at empowering Africans to determine their own futures. .

As president, Carter focused on civil and political rights. He then expanded his efforts to include social and economic rights as keys to public health.

“These are human rights due to humanity, and Mr. Carter is the single person in the world who has done more to advance this idea,” said Abdullahi Ahmed An-Naim, a Sudanese jurist. .

Even as a candidate, Mr. Carter reflected on what he would accomplish, he told Playboy magazine. Later on, we may realize that we had the opportunity to do great things in our lives, but we didn’t take advantage of it. ”

Just four years later, Prime Minister Carter welcomed new Prime Minister Robert Mugabe into the White House and echoed the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s words: “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” He welcomed Zimbabwe’s independence.

“Mr. Carter told me that he spent more time in Rhodesia than in the entire Middle East. And when you go into the archives and look at the administration, there’s certainly more in Southern Africa than there is in the Middle East.” said historian and author Nancy Mitchell.

Relations with Mugabe’s regime quickly deteriorated amid a deadly crackdown, and by 1986 Carter was leading a strike of diplomats in the capital. In 2008, Carter was banned from traveling to Zimbabwe for the first time. He called the country “a basket case and an embarrassment for the region.”

“Whatever the Zimbabwean leadership thinks about him now, Zimbabweans, at least those who were around in the 1970s and 1980s, will always see him as an icon and a tenacious promoter of democracy,” said the Harare-based said political activist Eldred Masunungure. Analyst.

After Carter’s death, Cyril Ramaphosa said that Carter also criticized the South African government for its treatment of its black citizens under apartheid, at a time when South Africa was “trying to join influential economies around the world.” The current president spoke on the X program.

The think tank, founded in 1982 by Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter, has played a key role in monitoring elections in Africa and brokering ceasefires between warring factions, but fighting disease is the third focus of the Carter Center’s work. It was the pillar of

“When I first came here to Cape Town, I almost got into a fight with South African President Thabo Mbeki because he refused me treatment for AIDS,” Carter told a local newspaper. “This is the closest I’ve come to getting into a fistfight with a head of state.”

Carter often said he was determined to outlive the last Guinea worm to infect humans. This parasitic disease, which once affected millions of people, was nearly eradicated in 2023 with only 14 cases recorded in a small number of African countries.

Carter’s quest included negotiating a four-month “Guinea Worm ceasefire” in Sudan in 1995, allowing the Carter Center to reach nearly 2,000 endemic villages.

“He taught us a lot about having faith,” says the director of the Guinea worm eradication program at South Sudan’s Ministry of Health, who grew up among people who believed the disease was just fate. Makoy Samuel Ibi said. “Even the poor call these people poor. It is a touching virtue that the leaders of the free world pay attention to them and seek to uplift them.”

Such dedication has impressed African health authorities over the years.

“President Carter worked for all humanity, regardless of race, religion or status,” Ethiopia’s former health minister, Lia Tadesse, said in a statement shared with The Associated Press. Ethiopia, the continent’s second most populous country with more than 110 million people, had no Guinea worm cases in 2023.

Associated Press reporters Farai Mutsusaka in Harare, Zimbabwe, and Michael Warren in Atlanta contributed.