Health insurance premiums in Vermont are high and rising.

Vermont’s average premiums for individual market plans are among the highest in the country, more than double the national average even after factoring in federal subsidies, according to data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

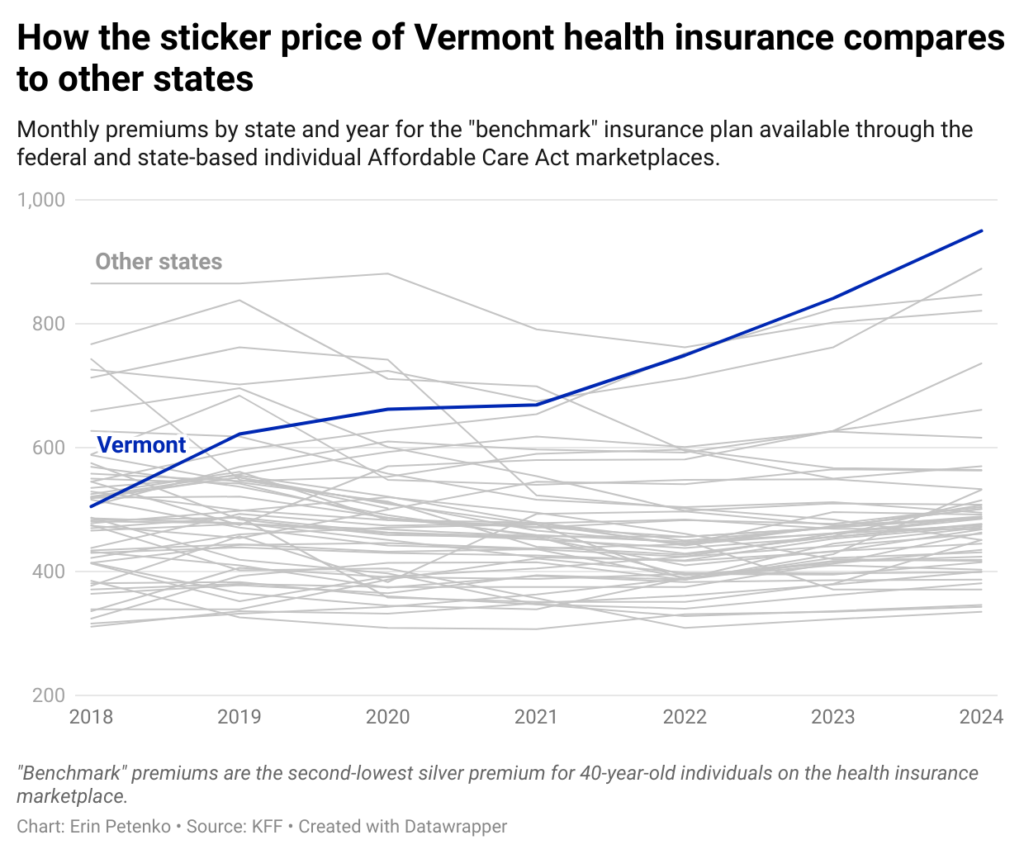

Premiums in Vermont are rising by double-digit percentages, a much higher increase than most other states, according to data from KFF, a health policy nonprofit.

“There’s no debate: Vermont is expensive,” said Mike Fisher, Vermont’s chief health care advocate. “You see it when you look at insurance rates. You see it when you look at private hospital rates.”

While the federal data only shows premiums for individual plans, Blue Cross Blue Shield spokeswoman Sarah Teachout said small and large group plans for employers are seeing similar cost increases.

“Hospital prices, drug prices, all that stuff is the same in the market,” she said.

Most Vermont residents don’t pay full price…

According to the Vermont Department of Health Access, roughly 30,500 Vermonters get insurance through individual marketplace plans, which are plans purchased by individual consumers, rather than employers, on the state’s marketplace, Vermont Health Connect (even plans that cover a family are called individual plans).

The average monthly premium (list price) for these plans is $874 as of January 2024, the highest in the country, according to federal data.

But most Vermonters who buy these plans don’t have to pay that list price because federal and state funds offset those premiums.

More than 89% of Vermonters enrolled in these plans received some form of federal subsidy to help pay for their plans, according to data from the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services for 2024. After these subsidies, the average premium fell to $243 per month, while Vermonters who received federal subsidies paid an average of $178 per month in premiums.

Vermont also helps low-income residents pay for insurance with a benefit called the Vermont Premium Subsidy, which caps the premiums Vermonters can pay for insurance plans they buy on the marketplace, based on their income.

About 14,800 Vermonters who are enrolled in individual market plans receive state subsidies for their premiums, according to the Vermont Department of Health Access, which manages the state’s marketplace.

The department’s data is more recent than that from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, but differs slightly from the federal figures. The average state subsidy provided to Vermonters was about $35 a month, according to the Vermont Department of Health Access.

The department said this would bring the average premium for Vermonters on individual market plans down to about $210 a month, though it would still be higher than premiums in about 40 other states, according to federal data.

Selecting a particular policy will also affect the list price of your premium, although it will not necessarily increase the actual cost of your policy.

In most parts of the country, health premiums for Marketplace plans are tied to the purchaser’s age. Older purchasers, who are more likely to be in poor health, pay more for their plans, while younger purchasers, who are more likely to be in good health, pay less. In Vermont, there is no such distinction, and younger purchasers pay relatively higher amounts for their plans, while older purchasers pay less.

read more

Vermont has also adopted a strategy called “silver loading,” which involves raising the list price of major silver insurance plans. (Marketplace plans are categorized into different metals, including platinum, gold, silver and copper, depending on premiums and deductibles.)

Because the federal premium tax credit is based on silver plan premiums, silver loading actually helps Vermonters save money: When premiums rise, Vermont can pull more funds in the tax credit, making premiums cheaper.

…But Premiums Are Still High

Caveats, circumstances and complexities aside, insurance in Vermont is still not cheap.

Even after factoring in federal tax credits, the average premium for an individual market plan in Vermont is $243, the sixth-highest state average in the country when Washington, D.C., is taken into account, according to federal data.

Health care advocate Fisher said small businesses, unlike individuals, don’t have access to public subsidies to help pay for employee health insurance.

“It’s tough in a way,” Fisher said. “Small groups are isolated. Small employers are isolated.”

Plans purchased through the small group market cover just under 28,000 people in the state, according to the insurer’s most recent state filings.

Earlier this month, the Green Mountain Care Commission, the main health care regulator, gave the go-ahead for MVP and Blue Cross Blue Shield, two private insurers selling in the Vermont marketplace, to further raise individual and small group premiums.

MVP premiums will increase by an average of 14.2% for individual plans and 11.1% for small group plans.

Blue Cross Blue Shield premiums will rise even further, by 19.8% for individual plans and 22.8% for small group plans.

Both insurers are raising premiums by significantly more than the national average of 7 percent, according to data from KFF, a nonprofit health care think tank.

KFF compared 324 private insurers across the country that reported tentative price increases. Vermont Blue Cross Blue Shield’s price increase was the eighth-largest in the nation, while MVP’s was 20th.

Blue Cross Blue Shield said those rate hikes were necessary to make up for what the state’s financial regulator described as a dangerous shortfall in the nonprofit insurer’s cash reserves.

“We know this is extremely difficult for our members, but it is a financially necessary step,” Don George, president and CEO of Vermont Blue Cross Blue Shield, said in a letter to community members last month. “Since May, medical claims have increased dramatically and members’ reserve levels have declined sharply.”

In a press release announcing the fee increases earlier this month, Green Mountain Care Board Chairman Owen Foster said the increases demonstrate “fundamental flaws in our health care system.”

“These fees are clearly unacceptable, but what’s even worse is a situation where insurance companies go bankrupt and can’t pay for patient care,” Foster said.

What are the cost drivers?

At a basic level, health care costs are determined by the product of the price of care and the amount of services used, said Carrie Cora, a health economist at Dartmouth College’s Geisel School of Medicine.

“As economists, we think of it as p times q, or price times quantity,” she said.

Vermont has seen both price and volume factors rise over the past few years. Over the past few months, Blue Cross Blue Shield, Vermont’s largest private insurer, which covers about a third of the state, has experienced what some administrators call a “claims surge” — a sharp increase in the number of claims filed by Vermonters who have received treatment.

Teachout, the Blue Cross Blue Shield spokesman, said the surge has been especially noticeable in the past three to four months, but claims have been rising for the past few years.

Jordan Esty, MVP vice president of government relations, said Vermont’s high premiums are due in large part to high health care costs and state policy decisions.

“Health insurance is expensive because medical services are expensive,” Esty said in an emailed statement. “Prices are much higher in Vermont than in neighboring states for the exact same services, like MRIs and lab tests. We need to have further discussion about why this is the case and whether these higher prices are fair and appropriate.”

Esty warned that Act 111, a recent law that limits when insurers can deny claims from medical providers, could also increase costs in the future, potentially by a further 6% by 2026.

“This estimated 6 percent increase comes on top of the ever-increasing costs of prescription drugs, hospital bills and other health care services provided in Vermont, resulting in consistent premium increases of 10 percent or more,” Esty wrote. “This is not sustainable.”

Over the past few years, Vermont hospitals have repeatedly asked for increases to surgical fees.

Health care providers say there are many reasons why. Costs have risen dramatically due to the use of expensive specialty drugs, such as the diabetes and weight-loss drug Ozempic, they say. Years of labor shortages have forced many hospitals and medical facilities to rely on traveling medical workers, who cost more than on-site staff. Vermont has a severe shortage of long-term care and assisted living facilities, and hospitals are providing care, often at no cost, to patients who have nowhere else to go.

Additionally, as Vermont’s population ages, residents have more complex and severe health care needs that require more frequent and more expensive care.

“We need more young Vermonters who don’t need as much health care, who aren’t taking as many medications, who don’t have as many chronic conditions,” Steven Loeffler, president and chief operating officer of the University of Vermont Medical Center, said during a meeting with health care administrators and Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders this spring. “We see it and we feel it every day.”

More bad news may be on the way: During the COVID-19 pandemic, the federal government expanded eligibility for premium subsidies, allowing higher-income earners to tap federal funds to pay for Marketplace plans, but without congressional action, those expanded subsidies are set to expire at the end of 2025.

“Many of us who have been looking at the ‘non-system’ of health care financing — how health care is funded — have been saying for years that it’s unsustainable and can’t continue,” Fisher said, “but it feels like we’re in an even more acute phase of it.”