Debbie Waldman

KFF Health News

In the 18 months since Francine Milano was diagnosed with a recurrence of the ovarian cancer she thought she had beaten 20 years ago, she has traveled twice from her home in Pennsylvania to Vermont, not to ski, hike or see the leaves, but to prepare for death.

“I wanted to have control over how I left this world,” said the 61-year-old Lancaster resident. “I decided this was the option for me.”

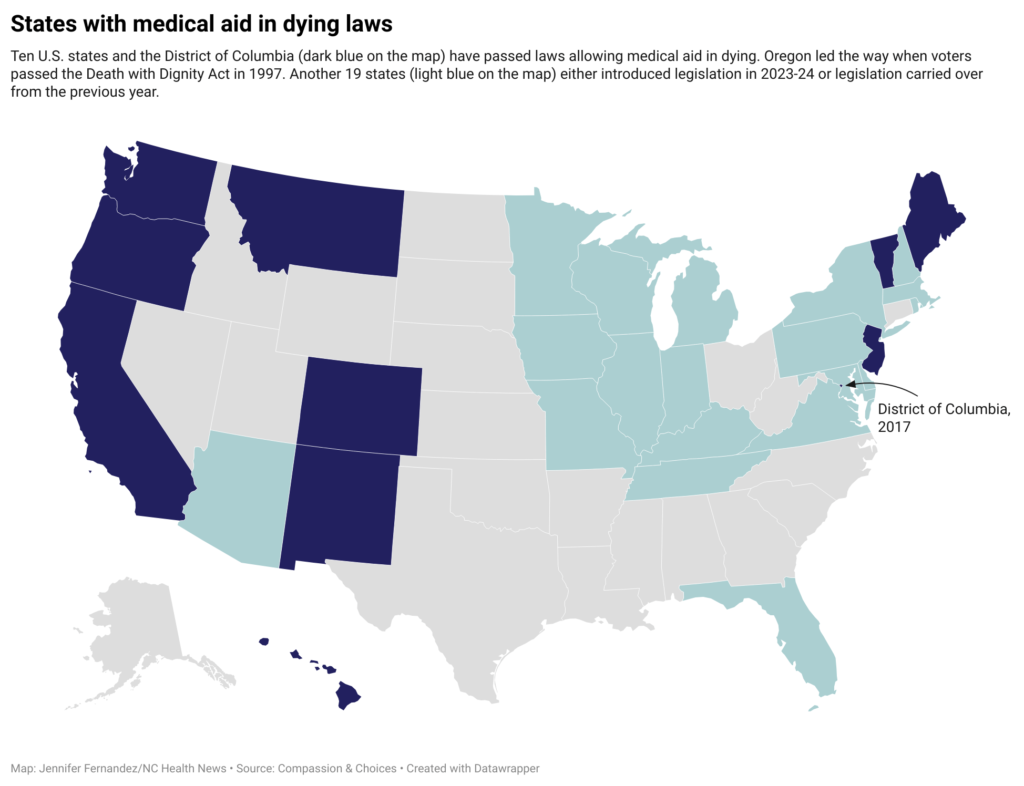

Medically assisted dying was not an option for Milano when she learned in early 2023 that her illness was incurable. At that point, her only options would have been to travel to Switzerland, live in the District of Columbia or one of the 10 states where medically assisted dying is legal.

But Vermont is dropping the residency requirement in May 2023, and Oregon followed suit two months later. (Montana effectively allows euthanasia under a 2009 ruling, but that ruling did not specify residency rules, and New York and California recently considered bills that would have allowed out-of-state residents to obtain euthanasia, but neither provision passed.)

Despite limited options and the challenges of finding a doctor in a new state, deciding where to die and navigating conditions that make it difficult to even walk to the next room, let alone get into a car, dozens of people have made the journey to two states that are open to terminally ill patients seeking assistance in dying.

At least 26 people have traveled to Vermont to die, accounting for about 25% of medically assisted deaths reported in the state from May 2023 to June of this year, according to the Vermont Department of Health. Twenty-three out-of-state residents have died in Oregon receiving medical assistance in 2023, just over 6% of the state’s total, according to the Oregon Health Authority.

Charles Blanke, an oncologist at the End-of-Life Care Clinic in Portland, thinks Oregon’s total is probably an underestimate, and he expects it to grow. Over the past year, Blanke has seen two to four out-of-state patients a week, about a quarter of his practice, and he says he gets calls from all over the country, including New York, the Carolinas, Florida and “a lot from Texas.” But just because patients are willing to travel doesn’t mean it’s easy or that they’ll get the results they want.

“The law is pretty strict about what you have to do,” Blanke said.

Death Expo lifts the veil of myth and mystery surrounding the final events of life.

Like other states that allow what’s known as physician-assisted euthanasia or suicide, Oregon and Vermont require patients to be examined by two physicians. They must have less than six months to live and be mentally and cognitively sound and physically capable of taking medication to end their life. Medical charts and records must be reviewed in the state; failing to do so would be practicing medicine out of state and violate medical license requirements. For the same reasons, patients must be in the state for the initial consultation, when requesting medication, and when taking the medication.

State legislators put in these restrictions as a safeguard to balance a patient’s right to seek euthanasia with a legislative mandate to not pass laws that harm anyone, said Peg Sandeen, CEO of Death with Dignity Advocates. But like many euthanasia advocates, Sandeen said the rules put an undue burden on people who are already suffering.

Diana Bernard, a palliative care physician in Vermont, says some patients can’t even show up for their appointments. “They end up having to reschedule because they’re not feeling well or they don’t feel like traveling,” she says. “We’re asking people to expend a lot of energy to get here when they really should have the option to be seen closer to home.”

Opponents of euthanasia include religious groups, who say taking a life is immoral, and doctors, who say their job is not to end life but to make people more comfortable at the end of their life.

Anita Hanig, an anthropologist who interviewed dozens of terminally ill patients while writing her book, “The Day I Die: The Untold Story of Euthanasia in America,” due to be published in 2022, said she doesn’t expect federal law to settle the issue anytime soon. The Supreme Court ruled in 1997 that euthanasia is a states’ rights issue, just as it did in 2022 when it ruled about abortion.

Nineteen states, including Milano’s home state of Pennsylvania, have considered euthanasia bills during the 2023-24 legislative session, according to the advocacy group Compassion and Choice. Only Delaware has passed a bill, but its governor has yet to act.

The situation in North Carolina

Compassion and Choice, a Colorado-based nonprofit advocacy group that tracks euthanasia bills across the U.S., cites three attempts to pass the bill in the North Carolina Legislature since 2017. A fourth bill, introduced during the 2023-24 session, focuses on studying the legalization of medical euthanasia in the state.

2017

House Bill 789, also known as the North Carolina End of Life Options Act, was introduced by five Democrats on April 11. No Republicans signed on to the bill. After passing first reading, the bill was referred to the House Rules, Timetable and Operations Committee.

2019

House Bill 879 was introduced on April 16. After passing first reading, the bill was referred to the House Rules Committee. This bipartisan bill had 12 sponsors.

2021

House Bill 780, introduced with bipartisan support on May 3, has been referred to the House Rules Committee. Twelve sponsors have signed on to the bill.

2023

House Bill 877, introduced on April 26, would have funded $150,000 for a North Carolina Medical Institute study to explore legalizing medical euthanasia in North Carolina. The bipartisan bill had 14 sponsors. Like the other bills, it never made it out of the Rules Committee.

Sandeen said many states initially enact restrictive laws (such as 21-day waiting periods or mandatory psychiatric evaluations) only to eventually repeal provisions that prove to be overly burdensome, so she’s optimistic that more states will eventually follow Vermont and Oregon’s lead.

Milano had hoped to go to neighboring New Jersey, where euthanasia has been legal since 2019, but residency requirements made that impossible. Oregon has more euthanasia providers than largely rural Vermont, but Milano opted to make the nine-hour drive to Burlington, which is less physically and financially taxing than a cross-country trip.

Milano knew she’d have to return, so logistics were key: She wasn’t near death when she visited Vermont with her husband and brother in May 2023. She figured her next trip to Vermont would be to claim her medication, which would require a 15-day wait to receive.

The waiting period is standard to ensure that people have what Bernard calls “time to think through their decision,” but she said most people have done it long ago. Some states have shortened the period or, like Oregon, created waiver options.

For patients, the wait can be tough, in addition to being away from their medical teams, homes and families. Blanke said he’s seen as many as 25 relatives attend Oregon residents’ deaths, but those from out of state usually only have one. And finding a place to die can be an issue for Oregonians in nursing homes and hospitals that ban assisted dying, but it’s especially difficult for out-of-state residents.

When Oregon dropped the residency requirement, Blanke put an ad on Craigslist and used the results to create a list of short-term lodging facilities (including Airbnb) that allow patients to die there. Nonprofits in states with euthanasia laws also create such lists, Sandeen said.

Milano hasn’t gotten to the point where he has to take his medication and find a place to end his own life — in fact, he’s exceeded the six-month approval period because he’s had a relatively healthy year since that first trip to Vermont.

But in June, she headed back to the hospital for another six-month grace period, this time with a friend who owns a camper. The two drove six hours to cross state lines, stopped at a playground and a gift shop, and then sat in a parking lot. Instead of driving another three hours to Burlington for an in-person appointment, Milano met with her doctor over Zoom.

“I don’t know if they use GPS tracking or IP addresses or anything like that, but I think it would have been scary for them to not be honest,” she said.

Her other fears aren’t limited to that. She worries that she’ll be too sick to return to Vermont when she’s ready to die, and that even if she did get there, she wonders if she’d have the courage to take the medication. About a third of people who are granted permission to euthanize don’t go through with it, Blanke says. For them, knowing they have the medication — the control — to end their life when they want is enough.

Milano said she’s grateful that she now has the ability to travel and enjoy life while she’s healthy enough. “I wish more people had the option,” she said.

Republish this story

You may republish our articles free of charge online or in print under a Creative Commons license.