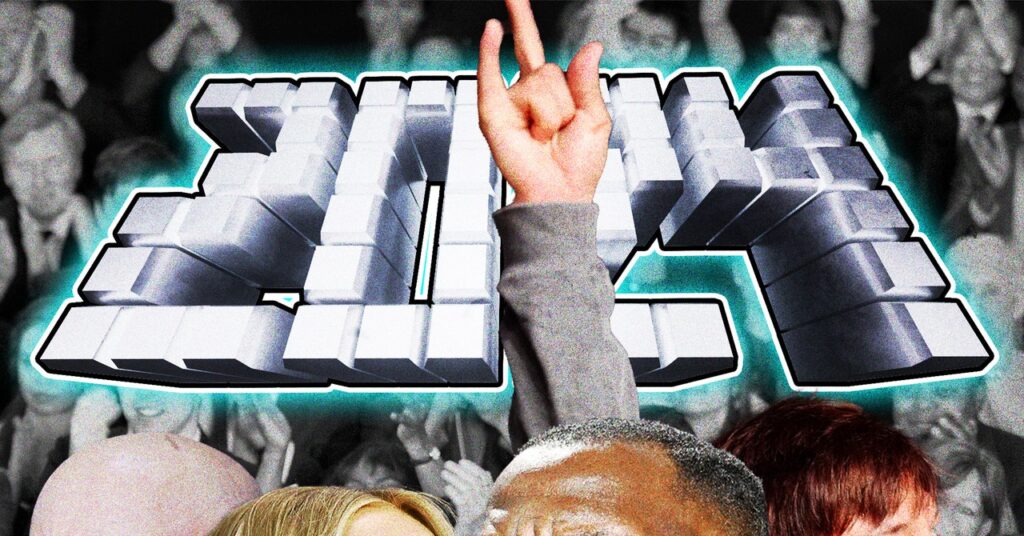

After years on the sidelines, content creators have become part of mainstream political media this year, bringing election news, analysis and political commentary to online fans, all of which bypass traditional news outlets.

Joe Biden, 81, was serenaded on camera by hilariously creepy TikTok singer Harry Daniels. Bernie Sanders tripped over Kamala Harris on a Twitch stream co-hosted by the anime catboy VTuber. Donald Trump collaborated with Jake Paul and Logan Paul, the quintessential creative brothers. Instead of taking time out for traditional sit-down interviews with mainstream news outlets, Ms. Harris and Mr. Trump turned to creators to galvanize voting and spread their campaign messages.

“As for our colleagues in the mainstream news media, there’s no value in speaking to the New York Times or the Washington Post in the general election because they’re already with us.” Rob Flaherty campaign deputy. Harris’ manager told Semaphore in December.

Influencing has grown into a $250 billion industry. More than 70% of Americans between the ages of 18 and 29 say they follow influencers on social media, according to a Pew Research survey last year. A more recent study released in November found that one in five U.S. adults gets their news from news influencers. Changes in media consumption have led to record spending on creator partnerships. Priorities USA spends at least $1 million on influencer marketing. The Harris campaign paid at least $2.5 million to a management company that books creators for political ad campaigns.

This election, creators were everywhere: at the Republican and Democratic conventions, fundraisers, rallies, and even parties at Mar-a-Lago. But the foundations for this creator’s takeover of political messages were in place nearly a decade ago. In 2016, Trump showed how social media platforms like Twitter can influence voters. During the 2020 campaign, former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg spent more than $300 million on his presidential campaign recruiting influencers and meme pages as paid digital proxies, and the Biden administration regularly recruits creators to the White House. We invited them to hold an information session.

By embracing creators, politicians are beginning to blur the lines between talking heads and journalists. Unlike reporters, news producers are often not bound by editorial standards or substantive fact-checking. One high-profile defamation case could change this, but for now it marks a difference. Many creators do a similar job to journalists: absorbing news, translating it, and communicating it to audiences online. But in the online political ecosystem, many of them are more like fans than objective observers. Some are clearly party activists. Still, they often provide access similar to traditional news outlets.