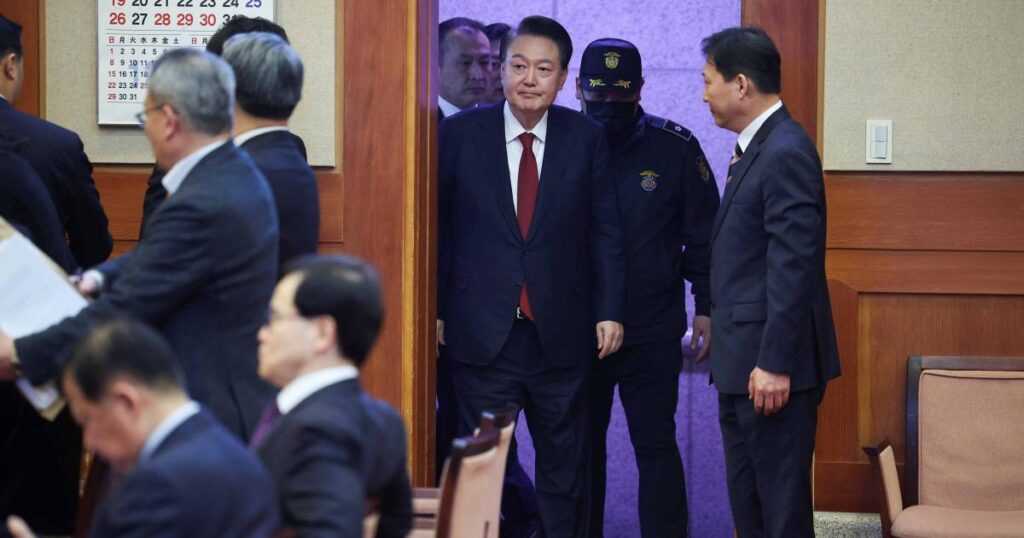

With democracies around the world under duress, South Korea seems to stand out as an example of resilience. President Yoon Suk-yeol’s attempt in December to seize undue power was knocked back by lawmakers’ swift action and a surge of popular outrage. Although the country’s institutions have held up relatively well, the upheaval also underscores the growing strain on South Korean democracy—and the prospect of crises to come.

On the night of December 3, Yoon declared martial law, only for the National Assembly to order the decree lifted within a few hours. Then, on December 14, Yoon was impeached and suspended from his duties. Less than two weeks later, with South Korea’s highest court still reviewing Yoon’s case, acting President Han Duck-soo was impeached as well. Citizens immediately took to the streets to protest Yoon’s power grab, and most members of Yoon’s party, however grudgingly, condemned his overreach. Pro- and anti-Yoon demonstrations have continued through the back-to-back impeachments, but they have stayed impressively peaceful. No one has died or been seriously injured; the police have been cautious, backing down when confrontations threatened to spin out of control.

Yet the depth of the turmoil is disturbing. Yoon’s martial law declaration was a huge shock, and his supporters’ rallying in his defense suggested some degree of endorsement in right-wing circles—Yoon is a conservative—for the cessation of constitutional governance. Most South Koreans had thought such antidemocratic attitudes had long been banished from the country’s political culture. And the impeachment of the acting president was almost as troubling. Two previous South Korean presidents have been impeached—Roh Moo-hyun in 2004 and Park Geun-hye in 2016—since the country’s democratization in 1987, but in neither case was the acting president also removed. South Korea has entered new constitutional territory: it is unclear what powers the “acting acting” president, Choi Sang-mok, the minister of economy and finance, even has.

Concerning, too, is the fear that this is not the last of South Korea’s recurring political crises. At their root is a structural problem: power is highly concentrated in the presidency, and deepening polarization is driving ever-fiercer fights over that office. Yoon’s stepping down might offer a reprieve, but not a lasting solution. South Korea’s political system needs bold reform to diffuse power and remove the incentives for presidents to attempt to rule by decree. Although discussion of such reforms started to build in December and has continued to today, momentum toward real change could easily fizzle out. It may be only a matter of time, then, until South Korea’s democracy is once again pushed to the brink.

STUCK IN GRIDLOCK

The South Korean presidency is imbued with a lot of power: it has wide latitude to make judicial and prosecutorial appointments, create budgets, and conduct foreign policy, without enough checks and balances. The executive overshadows other governing bodies, including the National Assembly, the courts, and local governments. This concentration of authority is a legacy of decades of dictatorial rule before South Korea’s transition to democracy in 1987. Unsurprisingly, the promise of holding the presidential office inspires intense, zero-sum competition between South Korea’s two main political parties. The ruling party is tempted to simply ignore the opposition, while the opposition, fearing that the incumbent could abuse the office and lock rivals out of power, resists the full exercise of presidential rule. The result is regular constitutional scuffles over the extent of the president’s authority, attempts by presidents from both parties to more or less rule by fiat, and threats by the opposition to impeach sitting presidents.

A worsening cultural cleavage between the political left and right has sharpened this fight over the presidency in the past few decades. South Korean voters tend to align with one party simply because it is not the other party, not because they prefer their chosen party’s policies—a practice referred to in political science research as negative partisanship. This tendency is not unique to South Korea; it became increasingly visible in the United States, too, when Donald Trump entered American politics, fueling the country’s so-called culture war. Wherever it appears, negative partisanship worsens political strife. Parties become vehicles to advance one side in cultural or identitarian disputes, precluding the pragmatism and compromise that are necessary for democracy to run smoothly. Neither bloc wants to budge, the norms and constitutional guardrails that limit power are continually threatened, and politics grows bitter and personalized.

Not all polarization is bad. Ideological polarization, or divergence based on policy differences, can be beneficial to a democracy by encouraging parties to develop distinct identities related to coherent policy platforms. But in South Korea, polarization has become more emotional than ideological. A study conducted by the political scientist Kim Sung-youn of Konkuk University found that the share of South Korean voters with negative feelings toward the opposing party jumped from 57.2 percent in the 2011 presidential election to an astonishing 86.5 percent in the 2022 election.

The depth of the turmoil in South Korea is disturbing.

This level of resentment, grievance, and even loathing for the other side makes it difficult to find any middle ground. South Korean conservatives and progressives increasingly identify each other as cultural enemies rather than just political opponents. As the list of issues on which they disagree grows longer, consensual governance becomes harder. Until the 2010s, the most divisive issue between the left and the right was foreign policy. South Korean conservatives were staunchly anticommunist and pro-American; progressives wanted outreach to North Korea and distance from American dominance. Conservatives accused the left of North Korean sympathies—a charge echoed in Yoon’s martial law declaration—whereas progressives saw the right as acquiescing to American imperialism. This disagreement led to large swings in South Korean foreign policy based on the president’s party affiliation. But on domestic policy, there was a broad consensus supporting an active economic development program and a moderately generous welfare state. Heated battles over government spending and cultural issues were rare.

In the last decade or two, however, the domestic consensus has been fracturing. Issues related to gender, family, sexuality, religion, and generational difference have become deeply divisive. Fundamentalist Protestantism has emerged as a strident, controversial voice in South Korean conservative politics. Feminism and women’s empowerment have sparked a backlash among younger South Korean men and others who blame the movement for the country’s extremely low birthrate and contracting population. For years, strong economic growth supported government spending on social programs, but policymakers increasingly face resource constraints as the country’s ratio of working people to retired people falls rapidly. Intergenerational conflicts loom as the tax base shrinks and the national debt rises.

Unhelpfully, South Korea’s many political cleavages tend to map onto the two main political parties rather than cut across them. The parties have thus become tied more to emotionally charged identities than to bundles of policy preferences. The result is partisan gridlock. Frustrated by the difficulty of governance, South Korean presidents are frequently tempted to wield their personal authority to force through their preferred policies. Yoon’s liberal predecessor Moon Jae-in, for example, sidestepped the legislature as he pushed a highly divisive policy of détente with North Korea, inviting increasingly hysterical right-wing opposition. President Lee Myung-bak, who served from 2008 to 2013, was so determined to advance a trade deal with the United States that his party shut out opposition legislators from a key part of the deliberations—and the lawmakers responded by attacking the closed doors of the hearing room with a sledgehammer and chainsaw, all captured on television. Yoon’s martial law declaration may be the most extreme example, but he is not the first to flirt with rule by decree.

CRISIS POINT

South Korea’s political fractures were on full display from the beginning of Yoon’s tenure in 2022. He had run a divisive campaign that emphasized right-wing social and foreign policy positions, including attacks on feminism, hints he would shut down the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family, and a pledge to shore up the U.S.–South Korean alliance after his predecessor had ostensibly undermined it with overtures to North Korea. He won the popular vote by less than one percentage point. For most of his presidency, Yoon’s approval rating hovered close to 30 percent, and it had fallen to around 25 percent before his martial law declaration.

Yoon’s unpopularity handed the opposition a large majority in the National Assembly after legislative elections in April 2024. The Democratic Party of Korea, the leading left-progressive party, used its new legislative dominance to persistently impede the Yoon administration’s attempts to govern. It proposed investigations into prosecutors pursuing corruption cases, which resulted in protracted institutional conflict as the administration took steps to block the investigations. Procedural battles ground policymaking to a halt. The DPK also accused Yoon’s wife of corruption, generating a salacious scandal that deeply wounded Yoon personally. South Korea was becoming ungovernable; the system seemed unable to overcome intense partisan divisions and deliver any kind of policy.

Yoon is not the first to flirt with rule by decree.

South Korean conservatives strongly suspected that gridlock was the DPK’s intent. The DPK assumed, correctly, that voters would blame the unpopular Yoon for the standstill, giving the party little reason to concede anything to a president whose right to rule it had never truly accepted. (Yoon, arguably, had only won the presidency in 2022 because a third-party candidate had split the vote on the left.) When Yoon issued the martial law declaration, he cited government paralysis as a reason to suspend regular order.

The opposition may have provoked Yoon, but his response was wildly disproportionate. Yoon did not seem to grasp that divided government—in which one party controls the executive and another the legislature—is a normal condition in modern democracies, not a national emergency that requires the suspension of the constitution. His actions, and his supporters’ defense of them, reflect how the South Korean right has embraced the dalliance with authoritarianism and conspiracy that is increasingly common among Western conservative parties, including the Trump-led Republican Party in the United States. Many of Yoon’s supporters have not admitted that he overreached and should therefore be removed from office. His party was split in the vote to impeach. On the streets, conservative protesters, frightened that the left could win the next election, have rallied to Yoon. They have waved “Stop the Steal” signs and stormed a court that was involved in the impeachment investigation, drawing disturbing parallels to the Trump supporters who, after Trump’s loss in the 2020 U.S. election, charged into the U.S. Capitol building. And similar to their counterparts on the Western hard right, Yoon’s most fervent followers cultivate an online culture that promotes conspiracies and accuses the left of succumbing to communist manipulation.

CHECKS AND BALANCES

The best outcome in the short term would be for Yoon to resign and admit he went too far in trying to declare martial law. Instead, he has dug in his heels, prolonging demonstrations on the streets and forcing a confrontation with police that ended with his arrest in mid-January. South Korea’s political system is paralyzed, and it is unclear how the pro- and anti-Yoon camps will respond when the Constitutional Court renders its judgment on Yoon’s impeachment.

But even if the current crisis is resolved relatively neatly, whether through Yoon’s resignation or a court verdict, South Korea will still have deeper problems to contend with. The cultural shifts polarizing South Korean society cannot be meaningfully addressed through political or constitutional action—these are changes that society itself must reckon with. Structural political reform, however, can help reduce the competitive incentives inherent in the country’s presidential system, lowering the stakes of elections so that intense divisions between right and left are less likely to produce crises of the kind South Korea is enduring now.

Part of the solution is to reduce the power of the presidency, which would ease the partisan combat over a single super-office. Such reform has been widely discussed in South Korea for years, and recent bad behavior on both the left and the right, culminating in Yoon’s tumultuous presidency, has underscored its urgency. These changes could take many forms. Instead of a single five-year term, for instance, the president could serve for four years and be eligible to run for a second term, which would increase the leader’s accountability to the public. The National Assembly could be granted greater authority to set budgetary priorities rather than respond to budgets submitted by the Ministry of Economy and Finance, as it does now. Legislative oversight of foreign policy and the judiciary could also be enhanced by making reviews of government activity a regular part of parliamentary practice instead of restricting the oversight role to appointing special prosecutors and investigations. Moves toward greater federalism, such as giving South Korea’s provinces and municipalities their own tax-and-spend authority, could further disperse political power.

Without institutional reform, crises are sure to recur.

Another type of reform would address the makeup of the National Assembly. Typically, the vast majority of seats in the legislature are held by South Korea’s two main parties, setting up the right and left for a clash. Election law reform could give smaller parties a greater chance at representation, relaxing this two-party standoff. Currently, around 15 percent of the members of the National Assembly are elected via proportional representation, in which seats are allocated to parties based on their share of the national vote rather than through direct contestation in a geographically defined district. In 2020, the National Assembly issued a rule to keep the two largest parties out of these seats to make space for smaller parties that might bring fresh ideas to the legislature. But the main parties got around this rule by setting up satellite parties to run on the proportional representation lists and vote with them when they got elected. Increasing the size of the National Assembly and expanding the share of seats filled by proportional voting could reduce the impact of satellite parties. Germany offers a potential model: half of its legislature is directly elected, and the other half is elected by party list, giving several small parties enough seats to play a meaningful role in governance.

Relatedly, changes to South Korea’s Political Parties Act could allow more parties to contest elections. The law sets excessively high requirements for establishing a political party: it must have a central organization in Seoul and at least five city or provincial party organizations, each with at least 1,000 members. Only national parties are recognized. If these requirements were loosened, regional parties could begin to contest elections. Without regional parties, it will be much more difficult to move away from the current two-party system or move toward federalism, both critical ways to dilute the excessive concentration of power in the presidency.

Unfortunately, big changes seem unlikely. For years, political scientists in South Korea have recognized the undue power of the executive branch, often referring to it as an “imperial presidency.” When presidential scandals occur, these critiques are part of the mainstream conversation, too, with calls for reform echoing on the news and in editorial pages. Yet no substantial reform occurred after two former presidents were impeached in 2004 and 2016, or when a third, Lee Myung-bak, was sent to jail under a cloud of scandal. Political parties have been unable to agree on limits to presidential power. And some reforms, such as changing the duration and number of presidential terms or granting the legislature more oversight authority, could require constitutional amendments. Moving toward federalism almost certainly would. Changing the constitution, unsurprisingly, is difficult: both a parliamentary vote and approval in a national referendum are needed, and no amendments have been adopted since 1987. Reforms to legislative elections may be easier: the National Assembly can, with the approval of the Constitutional Court, issue rules that affect its own composition, as it did in 2020. But such measures alone would not directly address the problem of excessive presidentialism.

The mere fact of three impeachments since 2004 suggests the South Korean presidency is too powerful, and deepening, emotionally charged polarization is only raising the stakes with each election. Without institutional reform, crises like the one Yoon has triggered are sure to recur. The centuries-old formula for making democratic governance work is to dilute power by distributing it. If it follows that script, South Korea could yet avoid repeating history.

Loading…