Getty Images

Getty ImagesWarning: This story contains descriptions of sexual abuse

The Pelicot rape trial, which ended in France on Thursday, held a terrible fascination for almost every woman I know. As it unfolded in an Avignon court, I found myself following every awful detail, then discussing it with my female friends, my daughters, colleagues, even women in my local book club, as we tried to process what happened.

For nearly a decade, Gisèle Pelicot’s husband had been secretly drugging her and inviting men he’d met on the internet to have sex with his “Sleeping Beauty” wife in the marital bedroom while he videoed them.

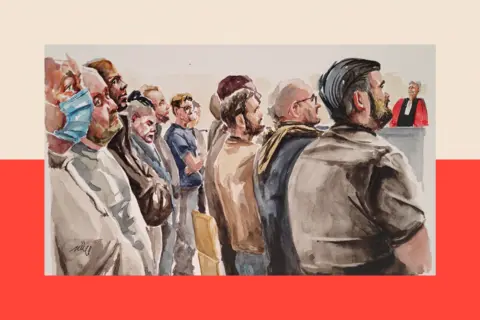

These strangers, ranging from 22 to 70 years in age, with jobs that included fireman, nurse, journalist, prison warden and soldier, complied with Dominique Pelicot’s instructions. Such was their desire for a submissive female body to penetrate, they blithely had sex with a retired grandmother whose heavily sedated body resembled a rag doll.

There were 50 men in court, all living within a 50km (30 mile) radius of Mazan, a small town in southern France where the Pelicots lived. They were, apparently, just like “any other man”.

One woman in her 30s told me “When I first read about it, I didn’t want to be around men for at least a week, even my fiancé. It just horrified me.”

Another in her late 60s, so close to Gisèle Pelicot’s age, couldn’t stop thinking about what men’s minds could be harbouring, even her husband and sons. “Is this just the tip of the iceberg?”

Reuters

ReutersAs Dr Stella Duffy, 61, an author and therapist, wrote on Instagram on the day the verdict was delivered: “I hope and try to believe #notallmen, but I imagine the wives and girlfriends and best mates and daughters and mothers of Gisèle Pelicot’s village thought that too. And now they know different. Every woman I talk to says this case has changed how she views men. I hope it’s changed how men view men too.”

Now that justice has been done, we can look beyond this monstrous case and ask: where did these men’s callous and violent behaviour come from? Could they not see that sex without consent is rape?

But there is a broader question too. What does the fact that so many men in a relatively small area shared this fantasy of extreme domination over a woman say about the nature of male desire?

How the internet changed the norm

It is hard to imagine the scale of the orchestrated rapes and sexual assaults of Ms Pelicot without the internet.

The platform on which Dominique Pelicot advertised for men to rape his wife was an unmoderated French website, which made it easier to bring together people who shared sexual interests, with no holds barred, than it would have been in the days before the internet. (It has now been closed down.)

One of Ms Pelicot’s lawyers likened the site to a “murder weapon”, telling the court that without it the case “would never have reached such proportions”.

But the internet has played a role in gradually changing attitudes to sex in consensual and non-abusive settings too, normalising what many might have once seen as extreme.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn the shift from old school skin mags and blue movies bought in a murky Soho sex shop to modern-day websites like PornHub, which had 11.4 billion mobile visits globally in the month of January 2024 alone, the boundaries of porn have expanded hugely. Adding in more and more extreme or niche activity ramps up the expectation, so “vanilla” sex may become mundane.

According to a survey of UK online users in January 2024, almost one in 10 respondents aged between 25 and 49 years reported watching porn most days, the great majority of them male.

Twenty-four-year-old university graduate Daisy told me that most people she knows watch porn, including her. She prefers to use a feminist site whose search filters include “passionate” and “sensual”, as well as “rough”. But some of her male friends say they no longer watch porn “as they couldn’t have a nice time having sex because of watching too much porn when they were just kids”.

A 2023 study for the children’s commissioner for England, Dame Rachel de Souza, found that a quarter of 16 to 21-year-olds first saw pornography on the internet while still at primary school.

At the time Ms de Souza said: “The adult content which parents may have accessed in their youth could be considered ‘quaint’ in comparison to today’s world of online pornography.”

Does porn really shape attitudes?

Children who regularly viewed porn on mobiles before puberty inevitably grow up with different sexual expectations than those aroused by Playboy in the 20th century.

While no direct causal link has been established, there is substantial evidence of an association between the use of pornography and harmful sexual attitudes and behaviours towards women.

According to government research before the Covid-19 pandemic: “There is evidence that use of pornography is associated with greater likelihood of desiring or engaging in sexual acts witnessed in porn, and a greater likelihood of believing women want to engage in these specific acts.”

Some of those acts may involve aggressive, dominating behaviour such as face slapping, choking, gagging and spitting. Daisy told me: “Choking has become normalised, routine, expected, like neck-kissing. With the last person I was seeing, I told him from the start that I wasn’t into choking and he was fine with that.”

But she believes that not all women will speak out. “And in my experience most men don’t want a woman to be dominant in the bedroom. That’s where they want to have the power.”

Forty years older than Daisy, Suzanne Noble has written about her own sexual adventures and now has a website and podcast called Sex Advice for Seniors. She believes that the availability of porn that depicts rape fantasies normalises an act that is rooted in violence and depicts rape as an activity women crave.

“There’s simply not enough education about the difference between re-enacting a fantasy that involves a pseudo-rape, with a completely non-consensual version of the same,” she argues.

From small ads to real life

Just as the internet brought porn out of backstreets and into bedrooms, it has also facilitated easier access to events in real life. Previously people into, say, S&M (sadomasochism), might have connected through small ads in the back of “contact” magazines, using Post Office boxes rather than mail to their own homes. It was a very slow and arduous way of setting up a sexual encounter. Now it’s far easier to connect with those groups online then plan to meet in person.

In the UK, it has become mainstream to find love and relationships through dating apps, and so too is it easier to connect with people who wish to try out particular sexual kinks, with a plethora of social apps such as Feeld, which is designed for people to explore “desire outside of existing blueprints”. Its online glossary includes a list of 31 desires, including polyamory, bondage and submission.

Albertina Fisher is an online psychosexual therapist who, in the course of her job, talks to her clients about their sexual fantasies. “There is nothing wrong with having a sexual fantasy — the difference is if fantasy becomes behaviour without consent,” she says.

Reuters

ReutersMale and female fantasies are different she tells me, “but they very often include submission and domination. The key thing about sexual preferences such as BDSM (bondage, discipline or domination, sadism, and masochism) is that it is safe, sane and consensual. What two people want to do together is absolutely fine.” This, she stresses, is the case when both consent.

All of this is, of course, entirely separate to the Pelicot case. “That is sexual violence,” she says. “And it’s extremely distressing that this can happen within what appeared to be a loving relationship. Acting out a fantasy without consent is an extreme form of narcissism.

“With the partner incapacitated, all their needs are denied. So you have a fantasy of a woman who you don’t have to worry about pleasing.”

Questions around desire

A key and problematic aspect of the whole question of fantasy is desire. In the post-Freudian age it has become a truism that desires should not be repressed. And much of the liberation theory of the 1960s emphasised self-actualisation through the realisation of sexual desire.

But male desire has become an increasingly contested concept, not least because of the questions of power and domination often entangled within it.

The men who stood trial in the Pelicot case struggled to see themselves as perpetrators. Some argued that they assumed Ms Pelicot had consented, or that they were taking part in a libertine sex game. As many of them saw it, they were simply pursuing their desires.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThere is a dark borderline where a very basic form of heterosexual male desire – (or the primal urge to have sex with a woman, or women, in the most uncomplicated manner) – can grow into a shared endeavour, creating an esprit de corps of boundary-pushing that may pay little heed or care to the female experience.

This perhaps explains why an OnlyFans performer, Lily Phillips, recently drew a huge queue of participants in her quest to have sex with 100 men in one day.

The tendency to objectify women may in some cases also develop into a desire to annihilate the whole question of female desire, let alone agency.

Obviously male desire takes many forms, most of an entirely healthy nature, but it has traditionally been constrained by cultural limits. Now those limits have shifted radically in the UK and elsewhere in the West, and the underlying conviction that the realisation of desire is an act of self-liberation amounts to a potent and sometimes troubling combination.

The appeal of Andrew Tate

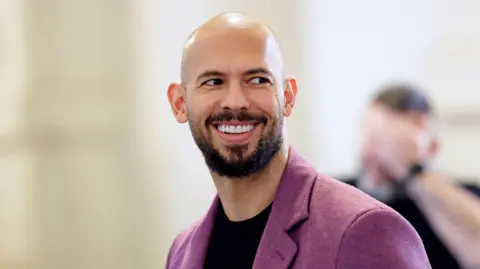

Andre de Trichateau, a therapist based in South Kensington, London, brought up the appeal of masculinist influencers such as Andrew Tate, a self-proclaimed “misogynist”, who has 10.4 million followers on X.

Mr de Trichateau says that he has encountered men feeling demeaned and displaced by the rise of feminism. “Some men don’t know who to be,” he says. “Men are socialised to be dominant but also expected to be in touch with their emotions, able to show vulnerability.

“This confusion can lead to anger, directed to the feminist movement, and (in turn this can lead them to) people such as Tate.”

With a 60% male client base, Mr de Trichateau observes that “men can be socialised to view power and dominance as part of their identity”.

“This is not to justify anything like the Pelicot case,” he continues, “but objectively I can see that such behaviour is an escape from powerlessness and inadequacy. It’s tantalising and forbidden.

“The case is disturbing because it shows the extremities that people will go to.”

He also pointed out that online groups such as the one Mr Pelicot used can be very powerful. “In a group you are accepted. Ideas are validated. One person says its OK then everyone will go along with it.”

EPA

EPAMany of the conversations during and since the Pelicot trial have focused on how to make the distinction between consensual and non-consensual sex and whether it should be better defined in law – but the problem is that what consent amounts to is a complex question.

As 24-year-old Daisy sees it, some women of her age tend to go along with men’s sexual preferences regardless of their own feelings. “They think something is hot if the man they are with thinks it’s hot.”

So, if heterosexual men, in particular, really are increasingly taking their sexual cues from pornography, then that prompts further questions about the changing shape of male desire. And if young women can feel that the price of intimacy is to go along with those desires, however extreme, then arguably consent is not a black and white matter.

Ultimately, there may be widespread relief that the Pelicot case is over and that justice was served, but it leaves behind even more questions – questions that, in the spirit of an amazingly strong French woman, are perhaps best discussed out in the open.

Lead image credit: Getty

BBC InDepth is the new home on the website and app for the best analysis and expertise from our top journalists. Under a distinctive new brand, we’ll bring you fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions, and deep reporting on the biggest issues to help you make sense of a complex world. And we’ll be showcasing thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. We’re starting small but thinking big, and we want to know what you think – you can send us your feedback by clicking on the button below.