Among the various technologies that have emerged in recent years, blockchain, NFTs, smart contracts, and generative AI are systematically changing the way art is authenticated, traded, rewarded, and created. They have not only helped to build a fully independent, natively digitized art world, but also changed the central premise of art from an object to be exhibited to a token to be traded.

The world of traditional art is still coming to terms with its digital duality, the NFT space also known as “Web3”. Contemporary art seems to be merging with the luxury industry at a time when big brands are looking for a stamp or “aura” of high culture. But today’s brands are conscious of a new generation of consumers who are accustomed to buying digital products in the virtual worlds of gaming platforms Roblox and Fortnite, and are as excited about big-name artists like Yayoi Kusama as they are about digital disruptors like Sasha Styles.

It doesn’t matter how the work is displayed, what matters is whether you connect more easily with it on your wall or on your phone.

Gunbrod, artist

Few articulate the new identity of digital artists as clearly as Gunbroode. Gambroud is a former Sony reportage photographer and art director who has become a successful artist working with machine learning. A prolific NFT collector, Gambroud sees the art experience in the same fluid terms as the marketplace. “The truth is, it doesn’t matter how the work is displayed. It’s about whether you’re more connected to something on your wall or something on your phone.”

Three years after the explosion of NFTs in 2021 and the sale of Beeple’s “Everydays: the First 5000 Days” (2021) for $69.3 million, only Pace Verso among major galleries has made a concerted effort to attract “crypto-native” collectors through its partnership with NFT platforms and generative art marketplace Art Blocks. Other major galleries around the world seem to be in denial about digital. But net artist, indie game designer and digital sculptor Auriea Harvey points out that “most sculptors today use some kind of digital process, just like a painter prepares their work in Photoshop. There’s nothing shameful about this.”

The same applies to collecting, according to Brian L. Frye, Spears Gilbert Professor of Law at the University of Kentucky College of Law. “The traditional art market works the same way (as does the NFT market),” he says. “Of course, if you buy a painting or a sculpture, you get the painting or the sculpture, but that’s irrelevant. The art market doesn’t value the object you own, it values what that object represents. What you’re really buying is an entry into the artist’s catalogue raisonné.”

Blockchain, a distributed ledger technology (DLT), updates traditional methods of authentication for the age of digital art. It also challenges the hierarchical structure of different media, as whatever a work looks like, it must be authenticated with a token or imprinted in cryptocurrency. For artist Mitchell F. Chang,NFTs separate the “artistic form” of an artwork (the medium) from its “commodity form” (the token), turning art into a transparent form of art money.

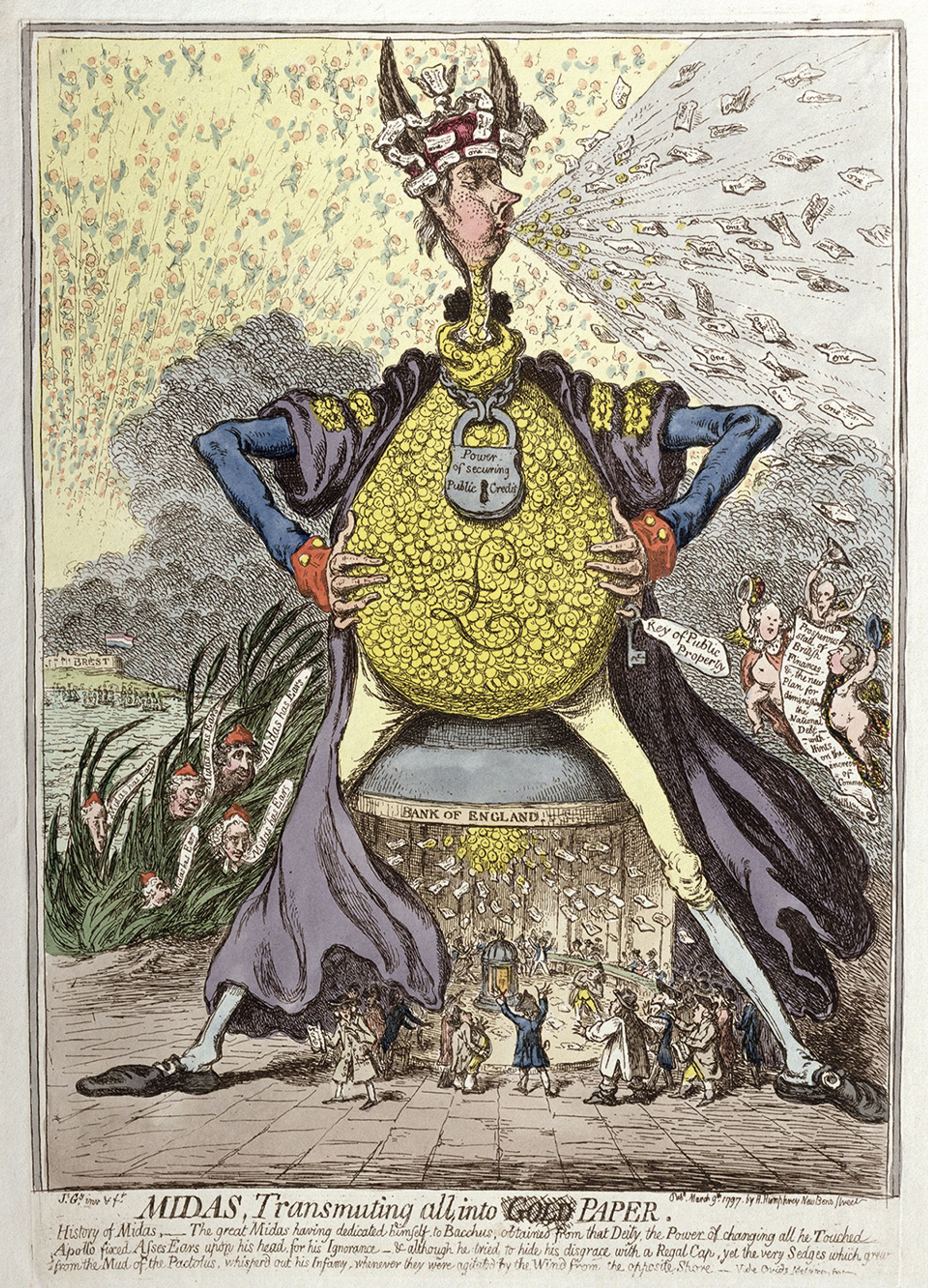

James Gillray’s “Midas: Turning Everything into Paper (Gold)” (1797) is also part of the Ashmolean Museum’s exhibition. Public domain, courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum

This situation is not without historical precedent. In the medieval Byzantine Empire, a token economy flourished that stamped every piece of art with the healing power of the Holy Spirit. In that context, it didn’t matter whether the piece was made of paint, mosaic, or metal; what mattered was that it received the divine stamp of approval, and “the incision was considered an act of consecration.” During the 2021 NFT boom, it was hard not to feel that the Holy Spirit as a driving force in the market had been replaced by hype. One of the shortcomings often cited by artists at the time was the lack of a critical framework for evaluating art after it was put on the OpenSea marketplace for NFTs. This was exacerbated by PFP (profile picture) projects such as CryptoPunks (2017). Its hybrid nature (both collector’s item and code-based generative art) destabilized existing categories of art.

Money talks

Today’s digital art world is different. Despite the desperate need for fluidity, the Web 3 is bolstered by new publications and platforms that listen to artists and seek to redefine the terms of the market. Museums, too, are expanding their canons, making space for crypto, generative and AI art within new histories of analogue and digital media. Tate Modern’s upcoming show “Electric Dreams” (November 28 to June 1, 2025) will examine early innovators in “optical, kinetic, programming and digital art” and their impact on the pre-internet imagination. Money Talks: Art, Society and Power An ongoing exhibition at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford (until 5 January 2025) looks at money as a medium of cultural expression, which in some ways will always have an imaginary value.

From parodies of commodity fetishism like Andy Warhol’s dollar signs (1981) Meshach Ghaba’s installation “Banks or Economy: Inflation” (2016) exposed Western currency as a framework of imperial coercion, while the Ashmolean exhibition culminates in a section dedicated to “The Age of Digital Ownership”. By juxtaposing the crypto-art projects of Sarah Mayohas, Lava Lab and Lea Pepe Wallet with Joseph Beuys’s defaced banknotes (which he subsequently put back into circulation), it connects two art worlds that have historically been separated. It also confirms the observation made by sociologist Max Heijven in his prescient study Art after Money, Money after Art (2018) that “art has become more financialised and money more ‘cultural’”. For the Ashmolean exhibition, I developed a site-specific edition of the project’s deliverables together with the literary artist Ana Maria Caballero. (2023-ongoing) In response to the Oxford Crown minted by Charles I during the English Civil War.

But it’s not just financial boundaries where art is expanding. Alexandra Daisy Ginsburg’s “Pollinator Pathmaker” was originally commissioned by the Eden Project. (as of 2021) is an algorithmic tool that generates planting designs for “living works of art” that support the greatest number of pollinator species. Ginsberg offers audiences a means (and planting instructions) to empathize with natural ecosystems. But by aligning art with computer science and ecology, she also reflects a broader movement toward practices that mutually inspire multiple disciplines with a more-than-human perspective.

Last year, writer and critic Charlotte Kent suggested that some of the most interesting art today resembles speculative design. Ginsberg is not the only former student of field-establishing Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby to have developed an art practice that could be described as transmedia. Margaret Humeau, Xin Liu, and Sputniko! (Hiromi Ozaki) have all acknowledged the influence of Dunne and Raby on their work, whose strength lies in their confident orchestration of emerging technologies. Holly Herndon and Matt Dryhurst prefer to call their practice “protocol art,” which uses AI as a “coordination technique.” For their next project, “The Call,” which opens at London’s Serpentine Gallery on 4 October, they collaborated with 15 ensembles from around the UK to develop a choral dataset that explores the kind of collaboration required to build AI systems defined by consent.

New technology developed by artists

Artists are also sharing the techniques they have developed: in October, the Paris Opera will present “Coddess Variations,” a collaboration between sculptor Hermine Bourdin, dancer Eugénie Dorion, film director Hervé Martin-Delpierre and choreographer Ania Catherine of the artistic duo Operator.The performance employs the operator’s generative choreography methodology, which generates sequences and allows audience members to collect the choreography in the form of an NFT. For Catherine, “it’s important to build a cultural bridge between an ephemeral art form like dance and contemporary art. The idea that dance can be collected might make people rethink whether dance deserves to be considered contemporary art and valued beyond entertainment and tradition.”

If co-creation reflects the increasingly networked nature of art, it is also essential for curators in what writer and curator Jesse Damiani terms “postreality.” For Damiani, “the curator’s first objective in postreality is to critically engage with realms of knowledge beyond art and to build networks of trust that enable knowledge sharing in all directions.” As its boundaries are being redrawn in new digital geographies, art’s role as a space for border thinking may be its greatest asset.