GLOBAL

![]()

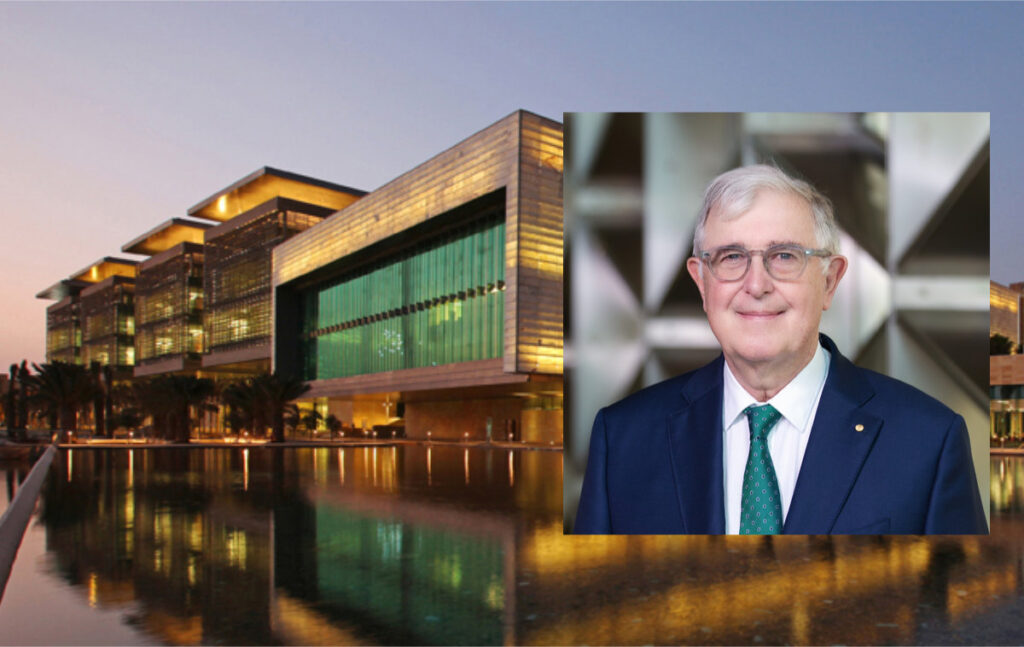

Sir Edward Byrne (72) has led three top universities on three continents. He took over as president of King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST) in Saudi Arabia in September, having previously been principal of King’s College London (2014 to 2021) and vice-chancellor of Monash University in Australia (2009 to 2014).

In a wide-ranging interview, Sir Edward – a British-born neuroscientist knighted for his services to education – discussed the role of Saudi universities in delivering both the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 for social and economic progress and world leaders’ internationally agreed agenda for sustainable development, Agenda 2030, comprising the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

He also discussed how university leaders negotiate complex challenges, from how to align with national priorities, which is fast becoming an existential question for universities, to driving gender and socio-economic equity and exploiting the potential benefits for universities of the development of artificial intelligence.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

UWN: You have been on a journey from Monash to King’s College London and now KAUST, holding leadership positions on three different continents in quite different contexts. Tell me what you have learned and what you are bringing from your experience at those institutions, and why you have chosen to take over at KAUST in Saudi Arabia?

EB: I have always had that new country focus. I am a child of two nations, born in North of England, in Tyneside, I went to Australia as a teenager, did medicine there, then came back to London to finish training as a neurologist, a brain specialist, did a research degree there, and then went back to a senior academic position in Melbourne.

But what I think is a little bit more unusual is having had senior roles in two countries of which I am a dual citizen.

So I got to know the academic scene in the UK fairly well and I know it in Australia very well. And I’ve learned a lot about running universities and perhaps making them as effective as I can help them to be – and they are very much a collective effort – in the complex world we are in.

This was the theme of the book I co-authored – The University Challenge: Changing universities in a changing world (Pearson, 2020) – with Charles Clarke, who was the education secretary in Tony Blair’s Labour government in the UK.

The world is so complex, probably more so than it has ever been, at least in my lifetime. And so many of the challenges – local, national and global – need clever, smart people working on them collectively, together, and a lot of the talent is in the university sector.

So universities have an absolute moral responsibility to step up to the plate, and perhaps be often significantly more focused on outcomes that are measurable, and that society needs, other than purely academic outcomes.

Now (the latter) are important too, because, of course, creating the knowledge and teaching young people well is the core of the business. But I think the applied impact side is becoming more and more central around the world.

That’s what took me to Saudi Arabia. I spent almost 20 years in leading roles of great universities, and quite honestly, I had settled into quite an enjoyable board career. But when I was approached about the possibility of KAUST, I was immediately quite interested, because I had followed KAUST’s progress as an attempt to successfully establish a very significant research university in a part of the world that hadn’t had universities at that level before.

I had followed, just through the news media, the progress the Saudi government was making towards modernising the country – and I came to realise KAUST had a central role in that process. So, (this is) an opportunity to have impact in a meaningful way, possibly even greater than I have had with previous roles.

UWN: When you talk about the Saudi process and progress, is that about transition from perhaps heavy reliance on oil and gas to a knowledge economy?

EB: Yes, but that’s only part of the story. Vision 2030 (Saudi Arabia’s plan for a ‘vibrant society’ and ‘thriving economy’) is not just words on paper; it’s a cultural and sociological reform process, as well as a broadening of the economic base, and it is being implemented and it’s progressing so rapidly that you can see the benefits emerging in real time.

KAUST was established in the main as an expat community where the late King Abdullah tested some initiatives in the Kingdom, like having men and women in the same class, an academic workforce involving both genders and more freedom for women within the campus confines. And now the Kingdom has moved decisively in that direction, moving from hardly any women in the workforce to almost 40% in just a few years; and half the drivers in Saudia Arabia are women, and it’s not stopping there; it’s constant.

UWN: KAUST was the first university in Saudi Arabi to have a mixed gender campus. Are you saying that this has been a driver of the other changes in the Kingdom in some way?

EB: It’s clear to me that it was a test bed for initiatives of that type which have now been implemented right across the Kingdom.

UWN: And is that driving of changes in achievement by gender reflected in the leadership of universities; what percentage would be women leaders? Or staff?

EB: Increasingly. The main criteria of recruiting faculty have been academic and research excellence, and there hasn’t really been any other criteria applied. So the faculty have quite a high degree of autonomy with very generous research support and there are quite a number of senior women professors in my senior team, which I’ve inherited, obviously, because I’ve only been there a few weeks.

One of my ‘direct reports’ is a woman. And if you go one level further down, what in the Kingdom they call ‘minus two’, there are lots of senior women on the team, so the vice-president who’s travelling with me is a woman.

UWN: Another aspect of the government’s Vision 2030 is about addressing inequality more broadly. Within universities that means improving equity in access and success more broadly. Is KAUST taking a lead on that?

EB: Yes, and it is worth noting that Saudi Arabia is quite unusual in that, of its 40 million population, two-thirds are under 35 years of age. It’s a young country, and its population is growing very rapidly. The late King Abdullah, his vision of education driving the country forward, is very much embraced by the current leadership, especially his Royal Highness, the Crown Prince.

So the percentage enrolment in tertiary education in Saudi Arabia is already very high, with strong financial support from the state.

And in KAUST’s case all education is free, and for a university of KAUST’s level this must be almost unique. It doesn’t charge fees, the students’ living needs are supported, and it takes students not only from Saudi Arabia but from around the world.

UWN: So it really is free, not just the tuition?

EB: Yes, at the moment. I’m not sure if that can be continued in the same way, but the support for students who couldn’t afford a high-level education will always be very, very high.

UWN: Is the research and learning conducted in English?

EB: Yes. Universities teach in English. The faculty are all almost exclusively international, with lots from the United States, lots from Europe, lots from the UK, and a spattering of Australians. It’s a research-active university at the highest level, so almost 10% of the faculty are high citation researchers, which is an MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) type level.

UWN: So tell me about your strategic objectives. What do you want to achieve at KAUST?

EB: I’ve come into a situation where an incredibly ambitious strategic plan has already been developed for the university, and my role is not to devise a new strategic plan, but to try to make sure we implement it. The plan, in essence, is to make a very significant contribution to the 2030 Vision for the Kingdom.

Its speed may differ, but in terms of objectives, it’s not so different from the rules we had in my last three universities. Certainly, in the United Kingdom, in Australia also, there has been an expectation from government that more and more of the output of the university has impact.

We’ve seen this in the funding changes in the UK, in the greater alignment of university intellectual effort with national priorities. I don’t see this as an existential question, because great research is what universities are all about in part, the other part being great education. Alignment of the research wherever possible and practical with benefits in the medium term to the societies that are paying for all of this seems to me to be a very reasonable proposition.

So it’s not replacing the need for Science and Nature papers. It is simply complementing them by making sure that the knowledge that is generated through that work has applied applications within a reasonable time frame.

UWN: Worldwide, there’s a lot of thought and leadership on this issue of how universities go beyond the very important roles of building knowledge and enabling individuals to fulfil their potential, to having an impact on society and actually helping society transform.

EB: This was very much the subject of the World Higher Education Conference 2022 in Barcelona.

And as you say, Saudi Arabia has Vision 2030. And then, for the world there is Agenda 2030, agreed by world leaders, which includes the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

And increasingly, university leaders are understanding the need to help fulfil those goals, and the need to actively go out and engage with communities to understand their problems and work with them to find solutions. So they are applying research in a very engaged way with communities.

UWN: Is that something you do in Saudi Arabia?

That’s my expertise, probably, as a university leader. You know, it’s probably a little easier for somebody with a medical health research background, because when one engages in medical research like I did for one (part) of my career, you’re doing it to cure human illness. You know, it’s never in dispute that that’s what it’s all about.

In the leadership roles I’ve had in other universities, it’s always been very clear that impact and outcomes that could be measured in a short and medium term are very important.

Obviously, universities are complex, and it goes without saying that much of the most important research is not realisable in that sort of timeframe, and that research needs to be nurtured and continued.

I very much like the sort of almost cartoon analogy which is sometimes used of the three quadrants – there should be four quadrants, but I think there are three. So there is the (Niels) Bohr quadrant of the pure research that is crucial to understanding the world around us, and that’s in every discipline. There is the (Thomas) Edison quadrant of rapid, immediate application, applied engineering in real time, (such as) the light bulb.

And then between the two, of course, there is the (Louis) Pasteur quadrant, which is research at the highest and most brilliant level. Pasteur founds immunology, he founds stereochemistry. But he is applied. And I think a lot of researchers are in that Pasteur quadrant. So you need a solid intellectual foundation of brilliant intellectual activity and science to do the things we need to do.

Of course, the idea that suddenly everybody pivots from brilliant, basic work to purely applied, well that’s not what a university is about. It’s about a community where people working in a collegiate atmosphere bridge these issues.

And obviously, at a research university like KAUST – which is one of the more applied universities because it is for science and engineering – there’ll be lots of faculty who are working on the more basic side of applied issues, a lot of faculty whose research is at the commercialisation edge, and a significant number who have launched companies and spin-offs already.

And the other thing, of course, which I learned from previous jobs, is that in terms of the development of new businesses and entrepreneurial activity, most of it comes from younger people, students who have that energy and want to pursue life in that direction, rather than going to academia.

UWN: You have mentioned the extraordinary context in Saudi Arabia where two-thirds of the population are under 35. Often what happens in countries where you have a large youth population and you have higher education expanding, and maybe research expanding, you get this problem that when they leave, there often aren’t enough jobs. This has happened in Arab countries and was a driver of the Arab Spring protests, for instance. How is KAUST addressing this issue?

EB: I think the issue in Saudi Arabia is that a lot of academic faculty jobs are emerging as the university sector continues to strengthen. It is obviously compared to the UK, and certainly the US, but also even Australia, a less mature environment in terms of the total ecosystem needed for successful commercialisation, spin offs and what have you.

When I worked in London at both University College London and King’s, I was incredibly impressed by the number of new ventures being developed, all over the country but especially in London, by young people in the hundreds of thousands.

Saudi Arabia hasn’t evolved to that stage yet, but it’s rapidly on that journey. That’s something that partnerships can help with. I am not only hopeful, I’m committed, as somebody who spent much of my career in this country, to strengthening partnerships between Saudi Arabia and the UK, especially around these areas of applied research and entrepreneurial activity.

UWN: KAUST is in a very different context than King’s College London or Monash. So how does the context affect your perspective as a leader? What is it that you need to do differently because of the context you’re in? For instance, Saudi Arabia is on the one hand a fast-growing emerging economy, but it is also in an area that’s riven with conflict at the moment. What do you see as the challenges of the context?

EB: I think there are several layers to that, and I’ve been thinking about that part a lot, obviously, before taking the job and after starting, because it’s the core of much of what I have to try to achieve.

But firstly, Saudi Arabia itself is a very quiet, peaceful, stable country. Although the situation is very fraught to the north, you don’t notice that in Saudi itself. It’s becoming more and more the centre of the Middle East at a time when the Middle East has become even more central in world affairs. So it’s full of opportunity.

On that background, visionary government is driving through this incredible change process which we can see day by day in 100 different ways, and their expectation is that things happen. They’re not talking about theoretical change. They’re talking about real change that is measurable against KPIs (key performance indicators) in both the economic and sociological domains.

UWN: So what does that mean for KAUST?

EB: The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia has invested a lot of money in KAUST. And it has used KAUST, among other things, as a vehicle to draw outstanding intellectual people into the Kingdom, who, as well as the academic outputs that we all know in educational research, often have responsibility for advising ministers in the key domains that the Kingdom needs the greatest advice in.

Now, this isn’t exclusively KAUST. But KAUST people are central to a number of key areas – water, dry land, agriculture, the Red Sea, the energy transition – and they are interacting with the most senior people in the Kingdom in supporting this change journey.

How many universities in the world have the prime minister as the chair of the (university) council? And the senior ministers in the government, supplemented by hugely influential international figures, comprising the bulk of the university council? Well, KAUST does, but I don’t know of any other.

UWN: That is interesting because in a piece you wrote for University World News back in 2015 you talked about how in order to be flexible and responsive to local and global challenges, it’s very important to have respect for university autonomy. How does that sit with having government on your board?

EB: It’s very interesting, because it gets back to the point you made earlier. Saudi Arabia is in evolution. KAUST exists now in large part to help the Kingdom fulfil its ambitions. And it’s a question, really, of everybody getting behind that and making sure the very best advice is available and given.

But there’s a parallel process, because another part of the evolution of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is a recognition that a degree of university autonomy is essential in the maturation of these great institutions.

So when KAUST was established, it was unique in that regard. And although there are direct lines to ministers, KAUST is established by statute as a completely independent institution with very significant endowment – through the late king – which is protected and supports the university.

But KAUST is only one university with a small number of students in a country where the universities sector is maturing quite rapidly. And the government is increasingly interested in looking at what a more autonomous model of universities would look like (just as in) the United Kingdom.

So there are discussions with a number of the leading Saudi universities, notably one in Riyadh, about how that might evolve as well. And how KAUST has evolved could be something of a model.

UWN: Another issue I wanted to talk about is the commitment to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals, or SDGs.

EB: The SDGs and alignment with them were a major part of previous jobs I’ve had. It’s something I’ve always been very interested in.

The university sector in the Kingdom is doing its best by the SDGs and it is a task for the whole sector, working as collaboratively as possible.

KAUST as, you know, puts its data in for the Times Higher Education Impact Rankings and gets a very high ranking in five or six of the SDGs. We have activities in a lot of these areas, and collaborations with other Saudi institutions but also international ones.

UWN: One question I’m interested in is: do university leaders reframe their institution’s mission to ensure that the whole university is aligned to achieving the SDGs? Does it matter whether they do that? And what does it take, as opposed to simply mapping out what you’re already doing and fitting it with the SDGs?

EB: That is theoretically, and practically, a little easier for institutions like KAUST, because it’s been established around key thematic challenges. And although many of those challenges are very prominent in Saudi Arabia, they are almost all global challenges reflected in the SDGs.

For example, improved free health care and well-being applies everywhere, not just to the Kingdom, the environmental issues apply everywhere, and the need for energy transition applies everywhere; the need to look after the oceans applies everywhere. The thematic themes around eliminating and massively improving sociological unfairness also applies everywhere.

You asked me earlier about gender issues. I have always been passionate about that. When I was at King’s I founded the Global Institute for Women’s Leadership and recruited former Australian PM Julia Gillard to lead that.

And another thing you asked about earlier, we are critically aware of universities doing their job. It is not just about educating the children of upper middle-class families: It is about giving everybody a fair crack of the whip.

KAUST has done its best to do that by having no financial issues around enrolment and being purely merit based. That is something I am definitely committed to continuing, and making sure of students of ability having access to the university regardless of their financial situation. But that is a complex issue I am just getting my mind around at the moment.

UWN: Lastly, I wanted to ask you about how the role of universities is changing. You alluded to it earlier because of the pressure to have an impact, an impact on the economy especially, because of the relationship with government funding. But there is also pressure from the impact of AI, and from increasing diversity in the different types of provider. How do you see universities evolving?

EB: That was the topic of the book I wrote with Charles Clarke, The University Challenge, which came out just before the pandemic. It did very well in sales and I think has been pretty influential on the British government. The whole focus of the book was about change.

Charles and I spent hours trying to encapsulate complex ideas. But we came up in the end with the key concept that the key role for universities going ahead is change.

That is understanding change in all of the areas you have just mentioned and others; gearing change to the benefit of society at large, educating young people to understand, implement and deliver change. And ensuring that as change developed and accelerated, it aligned with the overall needs of society in a moral and balanced way.

These, of course, are incredibly complex issues. And the thing that makes it challenging, difficult and potentially incredibly rewarding, as we just alluded to, is the speed at which change is developing at the moment. At times it is hard to keep up with.

The book does need updating. The world has changed a lot in the last four years. Generative AI hadn’t come out, for example, in the way it has. But you could see it was coming. And I think the basic principles in the book are truer than ever, although there may be better or more up to date examples.

UWN: So how are you addressing the issue of AI? Do you see AI as a threat or an opportunity?

EB: Oh no, it is definitely, in the main, an opportunity and it is not an issue that can be avoided or ignored.

You know, there is a higher-level aspect to thinking about this which is (that it represents) a massive transformation of society in many, many ways – much greater than even came with the printing press all those centuries ago.

But there are a whole lot more immediate and addressable and refinable questions that can be thought about in detail now, because the end story of this massive enhancement of the ability to manage, analyse and use ‘giga gigabytes’ of data or ‘mega gigabytes’ of data is not fully understood. It is happening in real time.

But the more immediate issues you can understand. So generative AI can write a very good essay, even if it doesn’t quite come out with something you can read out at a conference.

And some educators, especially at university level and even more at secondary school, have said this is really dangerous, because it is reducing the creative impetus in young people, making life too easy for them as the calculator did (when it replaced) the slide rule, which I used to use. I don’t think anybody misses that now.

And the educator who says we are just going to ignore this, we are going to force young people to do it the old-fashioned way because that will increase their self-reliance and internal creativity, has only addressed half the equation.

Because the other part of the equation is these young people are coming out into a world where these things are integrated and being used and applied everywhere, and a key task for them will be to understand that and integrate their activity into it and develop their creativity around it, not ignore it.

What we need is smart people to face the difficult questions and address them, not push them under the carpet.