By this time, Linnea Richardson had hoped to start splitting some of the profits with the people she had invested with in the Walbrook Junction Shopping Center in West Baltimore. But something happened.

Rite Aid’s bankruptcy happened.

This is no small thing: The Walbrook Rite Aid’s closure leaves a huge vacant space in the shopping center and, for now, blows a hole in Richardson’s ambitions to increase wealth for Black families through what he calls “inclusive ownership.”

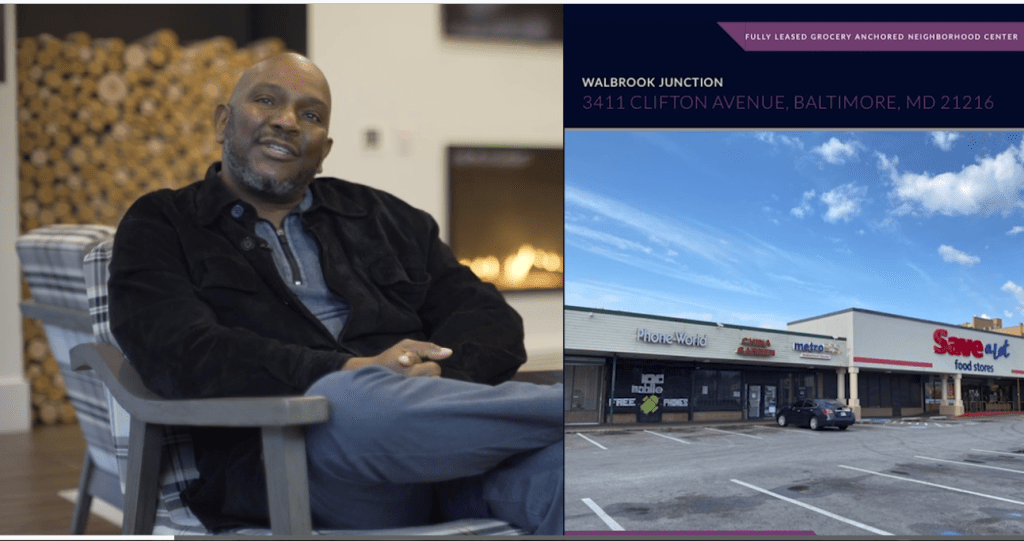

I first reported on Richardson’s big idea three years ago, when his Chicago-based social enterprise, TREND, began looking for investors in Walbrook Junction. For just $1,000, anyone over the age of 18 could become part-owner in the shopping center, which features tenants like Rite Aid and Save-A-Lot but was in need of an upgrade.

“When was the last time low- and moderate-income residents of Baltimore, particularly Black residents, had the opportunity to own a shopping center?” Richardson said in 2021. [neighbors] “If you are an owner and you improve the shopping center over time, you’re going to be proud of the shopping center, you’re going to protect it, and you’re going to use the shopping center in ways that you probably wouldn’t if you weren’t the owner.”

Richardson’s goals echo those of Democratic presidential candidate Vice President Kamala Harris in advocating for tax incentives for homebuilders and government subsidies for first-time homebuyers. “For people across the country, housing means economic security, the opportunity to build wealth and assets, and the foundation for a better future…” Harris said.

Why not try putting a stake in a shopping centre?

TREND, founded with grants from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundations and the Chicago Community Trust, has been carrying out Richardson’s grand vision for some time, buying two Chicago-area shopping centers, both in neighborhoods that are at least half black.

The events of 2020 prompted Richardson to double down on TREND’s efforts to increase wealth for people of color, which he called “a year of pandemic, protests and political turmoil” amid a backdrop of civil unrest and retail destruction sparked by the death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police.

Veteran urban planner Paul Brophy, former president of the Enterprise Foundation, got Mr. Richardson thinking about Baltimore. He looked at 10 shopping centers before making an offer on Walbrook, raising capital and arranging financing.

He then set up a crowdfunding page to solicit shares for the 47,070-square-foot shopping center, which closed with $332,000 from 130 investors, about half of whom were Marylanders, most of them from Baltimore or the greater Baltimore area, Richardson said.

Additional funding from the government has enabled TREND to refurbish the shopping centre, install a new roof and give it a local theme: “We Own This”.

But then the parent company of one of its major tenants, Rite Aid, filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy and closed 154 stores in 15 states, including several in the Baltimore area, including a large store in Walbrook Junction.

“We just reached full occupancy,” Richardson said, “we renovated a shopping center, we found a new Black entrepreneur to open a first-class laundry facility…”

And Richardson was hoping to hear that Rite Aid would be remodeling its stores.

Instead, he heard news of bankruptcy.

“This year was supposed to be a year to celebrate the fact that we’re able to give a dividend to our investors,” Richardson said, “but with Rite Aid’s space sitting vacant, we don’t have the cash flow to pay a dividend.”

Rite Aid left the store stuffed with fixtures and shelves, “and we had to pay to remove it,” Richardson said.

They’re currently looking for a new tenant — someone to take up the full 10,000 square feet of space left by the pharmacy — or maybe another pharmacy. Richardson said there’s still demand in the area.

“Our main objective is to get what we call a community-serving tenant,” he said. “We’re not looking to get another dollar store or another check cashing station. Are there health care providers or nonprofits that do senior services or workforce development?”

Richardson acknowledges that the space formerly occupied by Rite Aid may have to be divided to accommodate smaller businesses such as hair and nail salons, small pharmacies and bank branches, and TREND has been able to secure assistance from the state for grants to renovate the space for new tenants.

He said he hopes Rite Aid’s space will be filled so investors can see profits next year.

“The centre looks great now,” he says, “it has a new roof, new car park and a new façade. There is still work to be done – there is active drug dealing in and around the shopping centre, so despite investing in security cameras and security patrols, there are still operational challenges. But our aim is to make the centre an asset to the community and not a burden on the community.”

Using the same investment strategy and with the help of about 200 other investors, TREND is also redeveloping the long-abandoned Edmondson Village shopping center, also on the city’s west side. Richardson expects to hear some news about that site soon. “Stay tuned,” he said.

A mural at the Walbrook Junction Shopping Center in West Baltimore reads, “This Is Ours,” referring to the 130 individuals, many of them Marylanders, who invested in the shopping center’s renovation. (Rachelle Bynum/LaDonia Photography)