Reuters

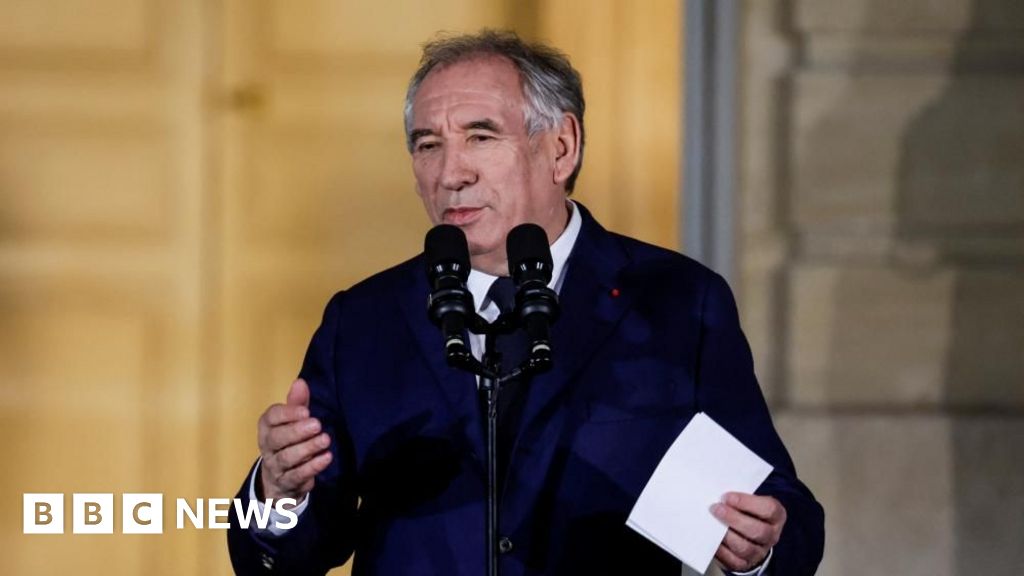

ReutersCentrist leader François Bayrou has become France’s newest prime minister, chosen by President Emmanuel Macron to end months of political turmoil.

The 73-year-old mayor of Bayrou, who is from the south-west and leads the MoDem party, said he was fully aware of the “Himalayan” challenges facing France, adding: “We won’t hide anything, we won’t ignore anything, we won’t do anything. I vowed not to leave any behind.

He is seen by Macron’s inner circle as a potential deal candidate, and his task will be to avoid the fate of his predecessor.

Former Brexit negotiator Michel Barnier, who was expelled by MPs nine days ago, welcomed Bayrou to Downing Street on Friday.

Mr. Barnier was defeated over a budget proposal aimed at reducing France’s budget deficit, which is expected to reach 6.1% of economic output (GDP) this year. Mr Bailloo said deficits and public debt were as much a moral issue as they were an economic one, and that “it would be a terrible thing to pass on to our children.”

Mr Macron is halfway through his second term as president, and Mr Bayrou will be prime minister for the fourth time this year.

French politics has remained deadlocked since President Macron called a snap election in the summer, with a BFMTV poll on Thursday suggesting 61% of French voters are concerned about the political situation. .

A flurry of allies praised Bayrou’s appointment, but Socialist Party regional leader Carol Delga said the entire process had turned into a “bad movie”. Manuel Bompard, leader of the far-left France Inboud (LFI), called it a “pathetic scene.”

The centre-left Socialist Party said it was ready to hold talks with Mr Bayrou but would not take part in his government. Party leader Olivier Faure said the Socialist Party would continue to oppose Macron because he had chosen someone “from his own camp.”

Bertrand Guay/Pool/AFP

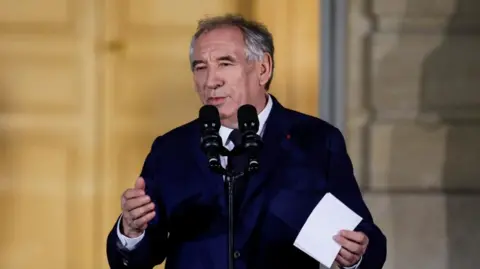

Bertrand Guay/Pool/AFPDespite Barnier’s ouster last week, President Macron has vowed to remain president until the end of his second term in 2027.

The prime minister cut short a visit to Poland on Thursday and was expected to name a new prime minister on Thursday night, but postponed the announcement until Friday.

He then met with Bayrou at the Elysée Palace, and the final decision was made a few hours later. But in a sign of the rocky nature of the talks, Le Monde newspaper reported that Mr Macron had given preference to another ally, Laurent Lescure, after Mr Bayrou threatened to withdraw his party’s support. He indicated that he had changed his mind.

Bairou arrived at the prime minister’s residence at the Hôtel Matignon late Friday afternoon. Even before his name was confirmed, the red carpet was being rolled out over the transfer of power.

His challenge will be to form a government that will not be overthrown in the way his predecessor, the National Assembly, was. The far-left France Inboud (LFI) is already threatening to call for a vote of no confidence as soon as possible.

Ahead of his inauguration, Macron held a roundtable discussion with leaders of all major political parties except far-leftist Jean-Luc Mélenchon and far-right National Rally’s Marine Le Pen.

The question is who can be persuaded to join Bayrou’s government, or at least agree to a deal that does not oust Bayrou.

Anne Renaud/AFP

Anne Renaud/AFPAt a time when the only means for a minority government to survive is to build bridges left and right, Bayrou has the advantage of having safe relations with both sides, reports BBC Paris correspondent Hugh Schofield.

Michel Barnier, who only took office in September, said on Friday that he knew from the beginning that his government would not last long.

Le Pen lost the election after her National Rally joined left-wing MPs in rejecting her plan to raise taxes and cut spending by 60 billion euros (£50 billion).

The outgoing administration has introduced legislation that would allow provisions in the 2024 budget to continue into next year. However, a replacement budget for 2025 will need to be approved after the next government takes office.

Bayrou said it was a “moral obligation” to reduce France’s deficit and debt.

Barnier wished his successor the best of luck, adding: “Our country is in an unprecedented and serious situation.”

In the political system of France’s Fifth Republic, the president serves a five-year term, appoints the prime minister, and selects the cabinet, which is appointed by the president.

Unusually, President Macron called a snap election for parliament in the summer following the poor results of June’s EU elections. As a result, France has reached a political deadlock, with three major political blocs: the left, the center, and the far right.

In the end, he chose Mr. Barnier to form a minority government that would depend on Marine Le Pen’s National Rally for survival. Macron now wants to restore stability without relying on the party.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThree centre-left parties – the Socialists, the Greens and the Communists – broke their alliance with the more radical left-wing LFI by taking part in talks with Mr Macron.

But they have made it clear that they want a left-wing prime minister, not a centrist one.

“I said I want either the left or the Greens, but I don’t think Mr. Bayrou is one or the other,” Green Party leader Marine Tondelier told French television on Thursday.

Patrick Kanner of the Socialist Party said that just because his party won’t join Bayrou’s government, “that doesn’t mean we’re going to bash it.”

Sebastien Chênes, a member of the National Assembly, said the “political line” Macron chose was more important for the party than who he chose. If Bayrou wants to tackle the immigration and cost-of-living crises, “he will find an ally in us.”

Relations between the centre-left and the radical LFI, led by Jean-Luc Mélenchon, appear to have broken down over the three parties’ decision to proceed with talks with President Macron.

“The more Mélenchon screams, the less his voice will be heard,” Socialist Party leader Olivier Faure told French television after the LFI leader called on his former ally to avoid a coalition deal.

Meanwhile, Marine Le Pen called for the next government to take into account the party’s policies on cost of living and create a budget that “does not cross the red lines of each party.”