Unlock the White House Watch newsletter for free

A guide to what the 2024 US election means for Washington and the world.

Which is worse? Having someone call your ethnicity in a way that you don’t like, or having someone knock on your door in the middle of the night, ask for proof of residency, and force you into a van? I asked because apparently the question is a lot harder than I thought.

There’s no question that well-meaning leftists are trying to put a lot of labels on me without my consent. I especially hate people who write to me and say I should call myself “mixed heritage.” Because this word makes me sound like a tomato.

So it’s understandable why the word “Latino” causes some of the people it describes to actively flock to Donald Trump. But then I realized that President Trump’s promise to deport 20 million people from the United States (a promise so central that it was featured on placards at the Republican National Convention) and, frankly, how this led Americans to say, “I don’t see it.” ” consider causing serious fear in a person. White Americans make the tomato story seem less problematic.

Anyone who is a member of a political party should never say that voters are fooling around because the customer is always right. But let me say this as someone who is not a member of a political party. If you’re letting the half-baked opinions of some social justice types dictate the direction of your vote, you’re doing something seriously wrong with your threat perception.

Nor is this issue limited to the American right. I’ve lost count of the number of people in British politics who have told me that Trump has a “four-year” term in office, but Brexit is permanent. That includes card-carrying Conservative members. Brexit is a huge blow to Britain’s economic prosperity, and if you think, as I do, that Britain’s presence in the EU has improved policy-making, it is a blow to the whole continent. But it is no match in substance or downside risk to a president pledging to water down or abandon the multilateral system that is a key part of America’s contribution to all of our security and prosperity.

What went wrong here? I think the common problem is that we live in noisy times. Strange and unhelpful ideas about race are not new, but now they’re on the BBC’s website. The rising margins of Brexit are always with us, but the self-righteousness of this metropolis is not being explained how Brexit happened, and instead socializing about the extra charges when ordering something from the continent. You can’t even complain in the media. There is ample evidence that being exposed to vehemently opposing opinions on social media, instead of broadening your horizons, can actually double down on what you were already thinking.

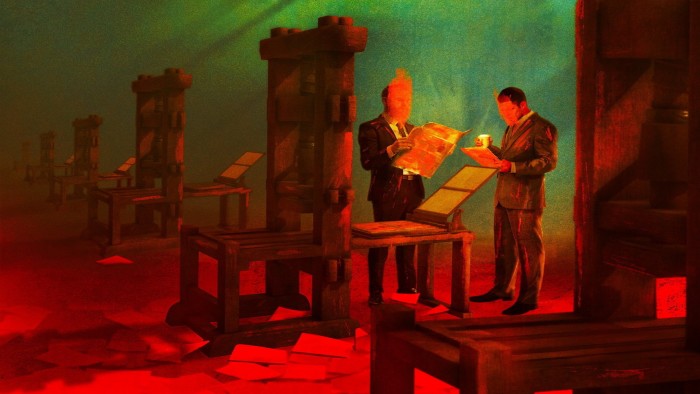

This is not the first time humans have had to endure increased noise around each other. The invention of writing and the invention of printing both represented similar information revolutions.

As Linda Roper explains in her forthcoming excellent book on the German Peasants’ War, Summer of Fire and Blood, the uprising of 1524-25 was not the first time that the power of the feudal lords was challenged by the peasantry. Nor was Martin Luther the first priest. Regarding the orthodoxy of the Catholic Church. But they were the first to benefit from the ease with which ideas could be disseminated thanks to the printing press. Although Luther may have simply referred to spiritual “freedom” in his writings, the peasants believed he was talking about something more fundamental and acted accordingly.

Of course, the Peasants’ War was not just about spreading ideas. As Roper explains, it was also about long-term economic and social issues. Just as Trump and Brexit are also about women entering the workforce, globalization, immigration and policy shifting middle-income jobs around the world. The effects of the global financial crisis will linger.

But the information revolution is a major part of it. We must once again readjust to the vastly increased amount of contradictory information at hand. Some people have a reaction called “news avoidance,” where they prefer to pay less attention to what’s going on. Others can never pull the plug. Neither approach leads to good decision making.

It took a century of war before we invented a new way of thinking: liberalism. This idea allowed Europeans to stop killing each other as a result of the last information revolution. Despite all the problems social media has brought us, we thought we were getting through this better. I’m not sure anymore.

stephen.bush@ft.com

Sign up here to receive Stephen Bush’s award-winning newsletter Inside Politics. Not yet subscribed to the FT? Try Inside Politics free for 30 days.