One freezing day this spring, Shammas Malik was slogging through an agenda that would overwhelm anyone. The new mayor of Akron, Ohio, had to meet with a city-council member who was upset over a recent shooting in his ward. The interim police chief stopped by to discuss the incident, which underscored that Malik still had to pick a permanent head for the troubled department. Meanwhile, the council was debating whether to fund his plan—a hallmark promise of his campaign—to open the government up for more direct resident involvement and input. He was planning for his State of the City address, which was due in just a couple of weeks, on his 100th day in office—also his 33rd birthday. Merely contemplating such a schedule exhausted me, and unlike Malik, I had the benefit of sustenance; he was fasting for Ramadan.

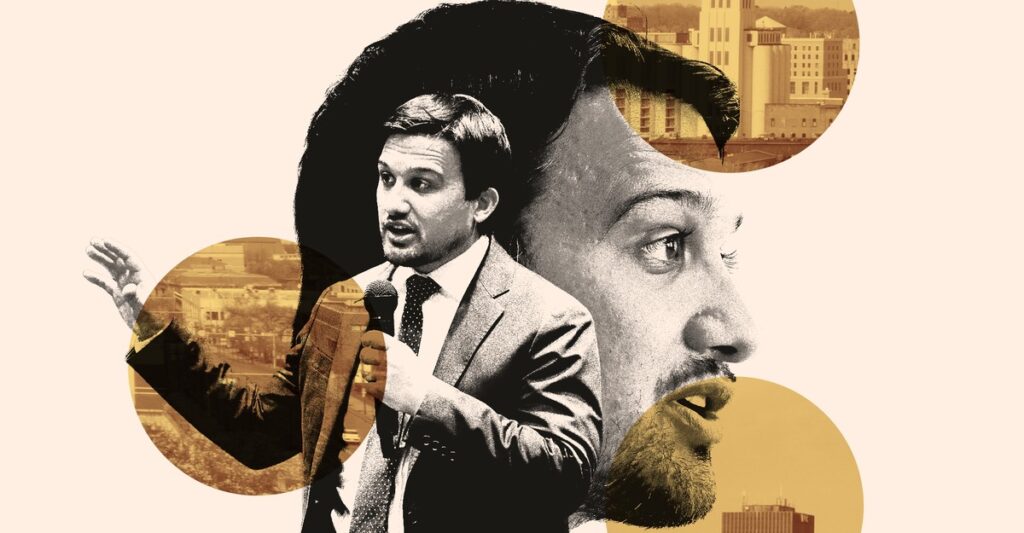

Malik, however, was plowing through it with the almost annoying equanimity of an ascendant political star. He is the youngest mayor and the first mayor of color in the city’s history, placing him among a crop of young, ambitious Democratic mayors of color in the Buckeye State, including Cleveland’s Justin Bibb, age 37, and Cincinnati’s Aftab Pureval, who is 42, both of whom were elected in 2021. In an election cycle where the top of the Republican national ticket—including Ohio’s junior senator, J. D. Vance—has offered up wild fabrications about immigrants eating pets in nearby Springfield, they offer a different version of Buckeye State politics.

Barack Obama won Ohio twice, but whether a young brown man with a “funny name” can still win statewide there is unclear. The state’s mix of impoverished rural precincts and aging, decaying Rust Belt bastions have tipped toward Republicans. Senator Sherrod Brown, the most recent Democrat elected statewide, is in the fight of his political life against the Republican Bernie Moreno. Malik, Bibb, and Pureval could represent a new generation of Ohio leaders, not only in their backgrounds and ages but also in their approach. They could, however, find their paths to higher office blocked by the country’s hyperpartisanship—a fate that has shortened the careers of countless promising Republicans in blue states and Democrats in red states, an invisible loss of talent that America pays for in ways immeasurable but profound.

Malik, who is biracial, with a Pakistani father and a white mother, is young for the role and looks younger. With a high, reedy voice and a baby face only barely disguised with a beard, he usually wears a suit—“If I’m going to be a 32-year-old mayor, I can at least look the part,” he told me—but that just makes him seem a little like a kid dressed up for a special occasion. In fairness, Malik will always seem like a kid to me: I first met him as a teenager, when he was friends with my little sister. When I told J. Cherie Strachan, a political scientist at the University of Akron, that high-school friends used to joke that he was getting ready to be mayor, she laughed. “And now he’s getting ready to be governor,” she said. “I can’t imagine that someone who is as ambitious as he is is going to stop at Akron.”

The real surprise might be that Malik is in Akron at all. Once, the city was the prosperous center of the nation’s tire industry, but its population has shrunk steadily since 1960. Firestone, Goodrich, and General Tire all left town; only Goodyear remains. The weather is bad. Any Akronite can reel off the names of many famous people from the city who left once they had a chance.

Malik could have been one of them. He excelled at Ohio State, graduated from Harvard Law School cum laude, and collected prestigious internships in Washington. He had no remaining family connections in Akron. Regardless, he decided to go home and take a job with the city’s lawyers in 2016, figuring he could always move to D.C. later. He found himself depressed and lonely, and when a friend asked if he’d be happier in the capital, he immediately answered yes. So why don’t you move? she asked.

“I think what I’m doing means something here, and I’m trying to find meaning here,” he said, recounting the conversation to me. “If I’m not (in Washington), probably somebody who thinks very similar to me, who’s going to work kind of the same as me, who’s going to do pretty much the same thing (will be). If I’m not here, that’s not necessarily the case.”

The answer conveys a lot about Malik: his earnestness, his diligence and sense of responsibility, his openness around topics like mental health. Obama—another biracial, Harvard Law–educated politician—is an obvious model, evident in Malik’s pragmatic approach to politics, his seriousness of purpose, and his speaking style. A shelf in his sparsely decorated office captures the range of his influences: The New Jim Crow, Robert’s Rules of Order, Bill Simmons’s The Book of Basketball, and the Quran.

Malik’s character was shaped profoundly by both of his parents—but in very different ways. The greatest influence on his life was his mother, Helen Killory Qammar, a beloved chemical-engineering professor at the University of Akron. She instilled a sense of service, a love of vocation, and a focus on education. “She always was trying to do the right thing,” Malik told the Akron Beacon Journal. “She was always treating people with kindness and dignity and respect and honesty.” Qammar died of cancer when Malik was 21.

Malik speaks frequently about her, but less so about his father, at least until the mayoral campaign. After Malik’s parents separated when he was 10, his father, Qammar Malik, a Pakistani immigrant, pleaded guilty to wire fraud, extortion, and impersonating a U.S. official in a blackmail scheme. During a mayoral debate in April 2023, Malik was asked how he thought about integrity. He shifted uncomfortably behind his lectern, as though wrestling with himself, then began to speak in a tremulous voice.

“I’m going to talk about something I never talked about in public before,” he said. “I have a father who’s a very dishonest guy, and this impacted me a lot as a kid. I talked to my dad through prison glass, and I don’t talk about it a lot because it’s something that is difficult to talk about, but it has guided my life to live every day with honesty.”

Despite his initial unhappiness upon returning to Akron, Malik stuck it out. When he learned that the city-council seat for the ward he grew up in was opening, he moved there and entered the race. Malik won the 2019 election in a stroll. (Driving around this spring, he was still new enough to his job that he was instinctively doing the work of a city-council member, sighing and making a note when he saw a light-pole banner that had become partially detached.) In June 2022, police shot and killed a 25-year-old Black man named Jayland Walker after a car chase, spurring protests. Three months later, Malik announced that he would run for mayor in 2023, challenging the incumbent Dan Horrigan in the Democratic primary. Within weeks, Horrigan announced that he would not seek reelection.

In Akron, as in many small and midsize cities, the Democratic Party dominates. The city hasn’t elected a Republican mayor since 1979, and the winner of the Democratic primary is a shoo-in for the general election. The city’s Democratic machine, including Horrigan, opposed Malik, which turned out to be a great asset in a city eager for change. Malik looked to Bibb’s successful race—featuring a young candidate who took on far more seasoned figures in Cleveland—as a model for his campaign.

The differences between Malik and other candidates were less about policy than philosophy. He ran down the middle on issues. In a race in which public safety was voters’ central concern, he promised both police reform and greater safety. Where he distinguished himself from the field was on governing style. During the campaign, he knocked on hundreds of doors and showed up at every event he could, leveraging his youth and energy. Wherever he went, he promised that as mayor he’d bring the same transparency and opportunity for public engagement into a city government that hadn’t felt very open or accessible for decades.

Strachan told me that Malik’s campaign was “facilitative, deliberative, inclusive, and focused on process.” These may be the hallmarks of a younger generation; Strachan noted that they’re also traditionally associated with a more feminine leadership style. And it was women who powered Malik’s victory. He won 43 percent of the vote in a seven-person field, and a postelection poll found that Malik won more votes from women than any other candidate won in total.

If anything, getting elected was the easy part. The council—perhaps eager to establish some leverage over an untested mayor—refused to fund a position to implement his public-engagement initiative. (“I don’t have to like it, but I’m gonna respect it,” he told me, paraphrasing the rapper Nipsey Hussle.) His attempt to change the city charter to allow him to seek outside candidates for police chief fell short. A mass shooting at a birthday party this summer shook the city and made national headlines; now some residents are clamoring for the police chief’s firing.

“It’s easy to get beaten down and just overwhelmed by the issues,” Tony O’Leary, a former deputy mayor who advised Malik’s transition into office, told me. “Shit just comes every day, no matter what you do or how well you prepare. It’s always the unexpected. It doesn’t matter what’s on your to-do list.”

When I spoke with Malik again in September, he said he was adjusting to the incrementalism of the job. The mayor has more power than a ward councilor, but also less chance to act unilaterally. His first nine months on the job, he joked, “have been like 54 years.” But Malik’s respect for process can mask a hard resolve.

“Everybody deserves to be treated with dignity and respect, right? But I should be confident in the things that I’m putting forward,” he said. “That doesn’t mean yelling, that doesn’t mean arguing, but it does mean being firm. I’m not going to bring something to someone unless it’s well thought out.”

Mayors don’t always have the luxury, or the burden, of ideology. Many of their most pressing issues aren’t partisan, and they may have to work with state and federal politicians with whom they disagree.

“When you’re dealing with the extreme MAGA-led Republican state legislature that we have in Columbus, I think it’s important to find commonsense, pragmatic Republican lawmakers that I can work with across the aisle who share my vision and love for Cleveland,” Bibb told me.

This fall, Donald Trump and Vance spent weeks fueling a national news cycle based on false, racist claims about legal Haitian migrants in Springfield, Ohio, and promising to deport them if elected. It fell to Springfield Mayor Rob Rue and Governor Mike DeWine, both Republicans, to refute those claims. Migration has taxed Springfield’s housing supply, but local officials also credit it with helping revitalize the economy.

In September, Malik joined a delegation of Ohio mayors that went to Springfield to meet with Rue, offer support, and compare notes. Back home, he told me that although he had no patience for fearmongering or racism, he understood the tension in Springfield.

“When there is a significant rise in population in a community, especially a city of 60,000 people, certainly there are going to be impacts. There’s going to be positive impact. There’s going to be challenges,” he said.

Akron experienced an influx of several thousand people, including many from Nepal and Bhutan, in the early 2000s. Malik said he was conscious of the concerns of longtime Akronites, but noted that, as in Springfield, population growth can help everyone. “I’m walking around a city that was built for 300,000 people,” he told me. “It’s now a city of 187,000 people. It doesn’t run if the population is 100,000.” (A couple of times, Malik half-jokingly tried to persuade me to move home too.)

Residents of bigger cities, which have more room and more liberal politics, may be receptive to this kind of argument—and to immigrants. Elsewhere, however, many Ohioans have been amenable to Trump’s message, focused on economic protectionism, nativism, and reduced immigration. His success there has taken Ohio out of the swing-state column at the national level. Broad political shifts, weak candidates, and gerrymandering have all but locked Democrats out of power at the state level. According to a count by David Niven, a political scientist at the University of Cincinnati, Democrats have won just one of 32 statewide races over the past decade, though the success last year of a constitutional amendment to protect abortion access has instilled some hope.

“To the extent that there’s a Democratic future, it’s the mayors, but what Ohio has been doing of late has been chewing up and spitting out Democrats with statewide aspirations,” Niven told me. Democrats hope that younger people and greater diversity will improve their statewide fortunes.

If the state ever turns purple again, Democrats will be looking to the people sitting in mayoral offices today and in the years ahead to win at the state level. “We need more mayors from big cities and medium-sized cities and small cities in this state working in the legislature, running for statewide offices,” he told me. (Bibb excluded himself from consideration, at least for the moment: “Right now, I’m just trying to get reelected in 2025.”)

Making the jump to statewide office isn’t easy, though, not only because of party affiliation but also because Ohio is regionally divided such that no mayor has much name recognition or reach across the state. In 2022, Dayton Mayor Nan Whaley ran for governor as a Democrat but was trounced by the incumbent DeWine. Malik told me that he’s heard the optimistic speculation about his future but he’s focused on his current job. “I ran for mayor because I think I can do this job,” he said. “I’m not running for state representative or state senator, because I don’t know state government. I’m not running for Congress. I want to do this job.”

For once, Malik doesn’t seem to be in a hurry. But if he ever wanted to kick the tires, he’d be in the right place.