Getty Images

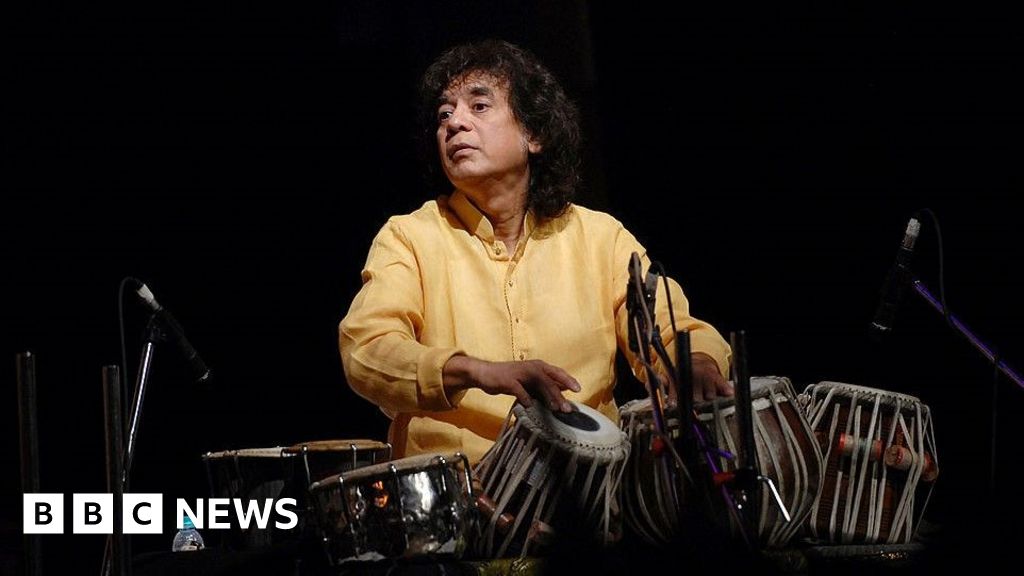

Getty ImagesZakir Hussain, the legendary tabla virtuoso and global ambassador for Indian classical music who has passed away at the age of 73, left behind a timeless rhythmic legacy that inspired generations.

A child prodigy, he collaborated with Indian classical icons such as Ravi Shankar, Ali Akbar Khan and Shivkumar Sharma, as well as global musicians such as John McLaughlin and George Harrison.

Born on March 9, 1951 in Mahim, Mumbai, he was the eldest son of Ustad Ararakha, one of history’s most iconic players of the tabla, India’s traditional hand drum.

Hussain’s journey from child prodigy to world-renowned percussionist was a masterclass in balancing tradition and innovation.

Hussein’s life revolved around rhythm from the beginning.

The tabla sound was his first language and his first “words.” By the age of 12, he was already active internationally, and as a teenager he was the accompanist for such heavyweights as Pandit Ravi Shankar and Ustad Ali Akbar Khan.

Although rooted in the Hindustani classical tradition, Husain has an insatiable curiosity that drives him to explore other genres, creating groundbreaking collaborations around the world.

In 1973, he co-founded Shakti, a group that fuses Indian classical music, jazz, and Western traditions to create a new global sound, with guitarist John McLaughlin.

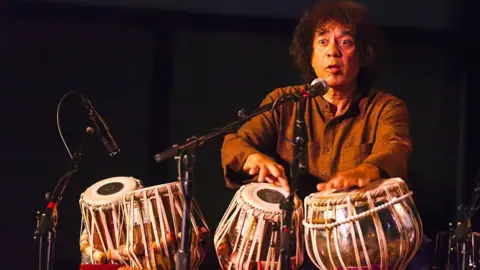

Over five decades, Shakti has evolved, featuring luminaries such as violinist L Shankar, percussionist Vic Vinayakram, and mandolin virtuoso U Srinivas.

Their first studio album in 46 years, This Moment won the 2024 Grammy Award for Best Global Music Album and was a fitting finale to their 50th anniversary tour. Hussain’s tabla virtuosity was crucial to Shakti’s success and the worldwide recognition of Indian rhythms.

Zakir Hussain’s contributions extended far beyond Shakti.

He was a key collaborator with Grateful Dead drummer Mickey Hart on Planet Drum and the Global Drum Project, winning Grammy Awards in 1991 and 2008.

He collaborated with banjo maestro Béla Fleck and bassist Edgar Meyer on the Grammy Award-winning As We Speak (2024), further cementing his status as a pioneer in cross-genre collaboration. I solidified it. He has also collaborated with musicians as diverse as Yo-Yo Ma, George Harrison, Van Morrison, and Billy Cobham, bringing Indian classical music to audiences around the world.

His ventures such as Tabla Beat Science, which fuses Indian classical music with electronic and world music, and his orchestral works such as Peshkar for the Indian Symphony Orchestra, demonstrate his constant drive to innovate while honoring his roots. was shown.

“The moment you think you’re a master, you distance yourself from other people,” Hussain told Rolling Stone India earlier this year. “You have to be part of the group, not dominate it.”

This philosophy made him not only a consummate artist, but also a lifelong learner and teacher.

Hussein’s flamboyance and the speed and precision of his performance earned him widespread praise.

In a review of his 2009 jazz performance at Carnegie Hall, the New York Times described his artistry as embodying “mischievous virtuosity.”

“He is both a formidable engineer and a whimsical inventor, devoted to frenetic play, so much so that he appears overbearing even when the wobbling of his fingers rivals the beat of a hummingbird’s wings.” There are very few.”

![Obituary of Grammy Award-winning tabla player 12 [AFP]Indian tabla player Ustad Zakir Hussain performs with mandolin player U Srinivas at the 14th Vasantsav in Mumbai on February 27, 2014.](https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/480/cpsprodpb/d38b/live/dd625160-bb84-11ef-b51d-3926bd0ae179.jpg.webp) AFP

AFPHis accolades are as numerous as the beats he created.

A recipient of the Padma Bhushan and Padma Shri awards, Hussain was also a National Heritage Fellow of the National Endowment for the Arts in the United States. He has delighted audiences in prestigious venues like Carnegie Hall and collaborated with jazz legends, Western classical orchestras, and Carnatic music masters.

Despite his global acclaim, Hussain remained deeply connected to his Indian roots. Mahim’s childhood in a modest cubicle, a large communal house, shaped his values.

“For the first three and a half years of our lives, we all lived in one room without a toilet. We had to use a communal toilet,” Hussain told Nasreen Munni Kabir. Ta.

Offstage, Hussain was an avid reader and a fan of Isaac Asimov’s Foundation series. He loved poetry, cricket and tennis, and counted Roger Federer among his heroes. His curiosity extended to the biographies of musical greats like Ravi Shankar and Miles Davis, reflecting his thirst for stories that transcended boundaries. Hussain later said that “I became famous in India” thanks to a TV ad for the popular tea brand Taj Mahal.

Although Hussein’s death marked the end of an era, it left an indelible mark on world music. Kabir, who chronicled his life, captures his essence aptly. “Zakir’s extraordinary playing and the extreme rigor he brought to his art made him a phenomenon.”

For Hussain, music was not just a career, but also a spiritual journey, a way to connect with people, traditions, and cultures around the world.

Hussein remained active in his later years, performing, teaching, and composing.

“Being a student and having a desire to learn keeps me going. The opportunity to be inspired by young musicians out there helps me reinvent myself. It doesn’t affect my energy and motivation,” he said last year.