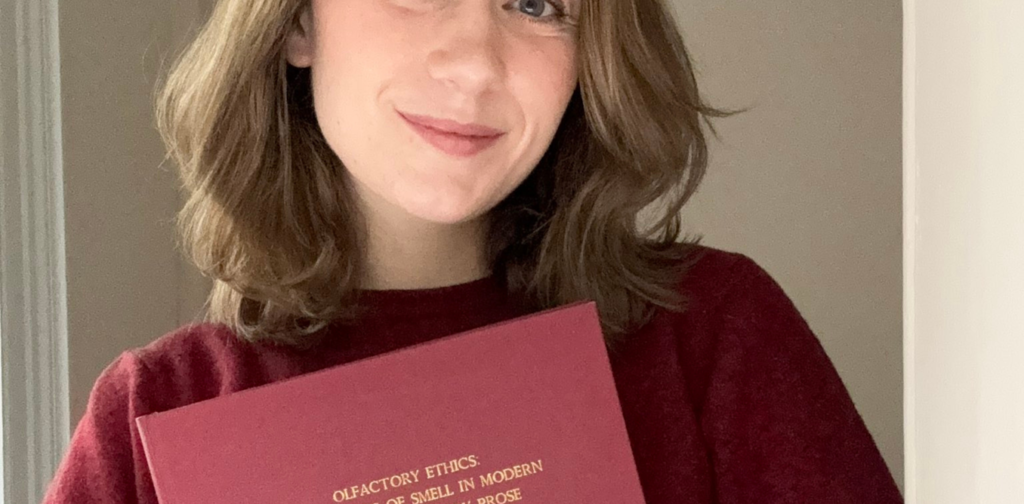

In November I celebrated completing my Ph.D. After three and a half years of writing and research, it was an opportunity I wanted to share with my academic network, so I posted a photo of myself holding a physical copy of my dissertation on X. The post garnered 120 million views and sparked a firestorm. The title, “Olfactory Ethics: The Politics of Smell in Modern and Contemporary Prose,” attracted a lot of anger.

This title received criticism from those who deliberately misrepresented the nature of the study. The phrase “smell is racism” has become a misplaced cliché. One user commented that this was a study in “why are we racists and classists who don’t like it when people display unsanitary body odor?”

My thesis studies how certain writers of the last century used smell in literature to indicate social antagonisms such as prejudice and exploitation. This also connects to our real-world understanding of the role our senses play in society.

For example, George Orwell wrote in The Road to Wigan Pier (1936) that “the real secret of classism in the West” could be summed up in four terrifying words: “The lower classes stink.” There is. Orwell reveals the harm that this type of message causes and how to counter it.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a hand-picked selection of the latest releases, live events, and exhibitions delivered straight to your inbox every two Fridays. Sign up here.

It is well documented that smell has been used to legitimize expressions of racism, classism, and sexism. Since the 1980s, researchers have evaluated the moral impact of perceptions and stereotypes about smells.

My paper adds to this research by evaluating the contribution of a range of books and films that take smell seriously. In each of the texts I have examined, the sense of smell plays a role that goes beyond mere sensory perception.

We include examples from well-known works by George Orwell, Vladimir Nabokov, J.M. Coetzee, and Toni Morrison, as well as notable recent examples such as Bong Joon-ho’s film Parasite.

I believe that smells very often evoke identity in a way that is intended to convey a person’s value or status. For example, in Parasite we hear a working-class man say that his employer “smells over the line,” which the director says “shatters basic respect for other human beings.” He describes it as a moment.

Some authors draw on the long history of scent-based discrimination to explore its relevance in modern society. For example, during the transatlantic slave trade, black slaves were said to stink, a misconception that contributed to their dehumanization.

In Toni Morrison’s novel Tar Baby (1981), set in the modern day, one of the protagonists makes a racist comment to a black female character, saying, “I know you’re an animal because you smell.” It uses associations.

I find it difficult to refute people’s ideas that certain smells are associated with certain identities. This can be due to strong emotional and physical reactions caused by smells.

Although we often think of our desire to avoid bad odors as an instinctive defense mechanism, evidence shows that we are taught which odors we find unpleasant. This is because children under the age of two are almost completely devoid of aversive responses. In other words, our sense of smell is shaped by society and influenced by society’s pervasive prejudices.

I also argue for the personal and social functions of reading and critically engaging with literature whose authors engage closely with smell. The texts I consider in my paper introduce readers to new ways to understand their sense of smell.

For example, in Sam Byers’ 2020 novel Come Join Our Diseases (2021), the characters thoroughly embrace their stench and draw attention to the harmless nature of doing so.

I therefore propose that books and films can not only document the politics of smell, but also foster and test new insights into our own sensory smells.

The fact that many commenters were initially unconvinced that smell could be a useful topic for academic discussion speaks to the widespread neglect of smell. After all, smell is one of the primary ways nearly all of us interact with the world, and it deserves more attention.