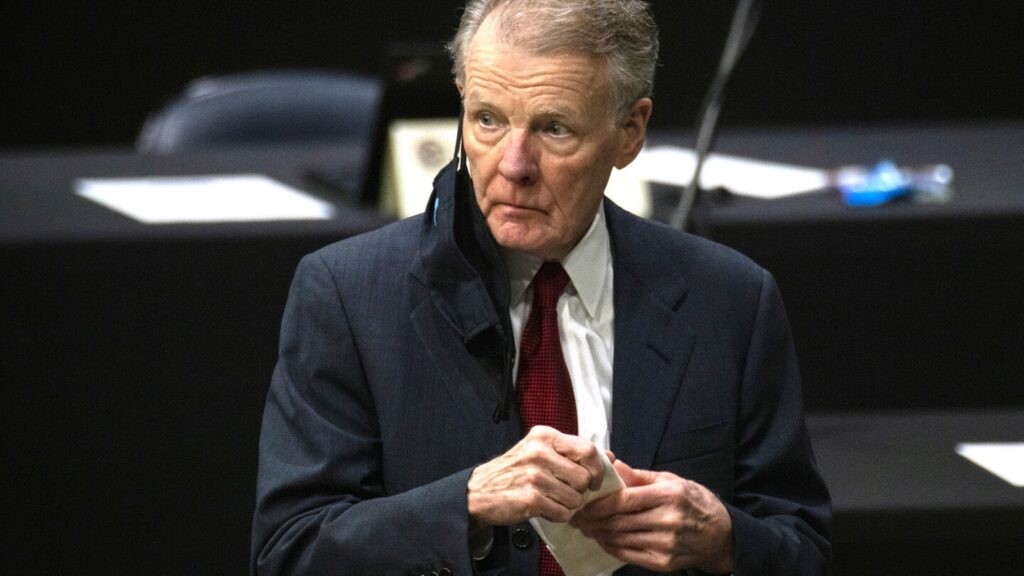

CHICAGO (AP) — Once hailed as oflongest-serving legislative leader Michael Madigan, the man in American history, will appear in federal court this week on charges that he used his enormous influence to run a “criminal enterprise” to amass even more wealth and power.

Former Illinois House Speaker Paid In a multi-million dollar extortion and bribery scheme that also included the state’s largest utility company, ComEd.

Much of the evidence, from wiretapped phone calls to videotaped meetings, has been released in open court. A thorough investigation into public corruption has already resulted in a conviction. Member of Parliament and Madigan’s former chief of staff.

But starting Tuesday, the spotlight shifts to the Chicago Democratic Party, once considered the most powerful force in Illinois politics, as potential jurors make their first court appearances.

“This is the top of the mountain, the very top,” said former federal prosecutor Phil Turner.

Let’s take a closer look at this case.

What are the charges against Madigan?

Mr. Madigan, who served as chairman for more than 30 years, is charged in a 23-count indictment with bribery, wire fraud and racketeering conspiracy for using interstate facilities to assist in attempted extortion.

Federal prosecutors allege that he used his role as chairman as well as other positions of power, including as chairman of the Illinois Democratic Party. He is also suspected of profiting from private legal work illegally directed to his law firm. Mr. Madigan’s mission was to “increase political power and economic well-being while generating income for political allies and collaborators.”

For example, he is said to have used his influence to pass legislation favorable to the utility company ComEd. In return, ComEd offered Madigan supporters kickbacks, jobs and contracts.

Madigan’s longtime confidante, Michael McClain, 76, is also on trial and has already been convicted in another related case. Last year, a federal jury convicted McClain and three others. bribery conspiracy ComEd is involved.

Madigan, 82, has “categorically” denied any wrongdoing.

“I am not involved in any criminal activity,” he said when the indictment was announced in 2022.

Madigan’s leadership was a return to old-fashioned machine politics.

The trial marks a stunning political fall for a leader who lasted three years in office. governor Land in prison.

“This guy always had a reputation for being untouchable,” said Turner, who was not involved in the case.

Mr. Madigan, the son of a Chicago district chief, was first elected to Congress in 1970. He served as chairman from 1983 to 2021, except for two years when Republicans were in power.

Madigan represented the area southwest of downtown near Midway International Airport. Middle-class neighborhoods are his power base, and his supporters, many of whom are government salaried workers, made sure to show up to tour neighborhoods and register voters.

He set much of Illinois’ political agenda and determined which bills received votes. He controlled multiple political funds and could choose which candidates ran for office. Madigan also directed political mappingsecuring a border favorable to the Democratic Party.

“He becomes a party,” says Kent Redfield, a professor emeritus at the University of Illinois at Springfield. “It will be the Mike Madigan party.”

At the same time, he kept a low profile and preferred to work behind the scenes. Madigan wasn’t the type to participate in parades or ribbon cuttings. He famously did not have a cell phone.

His leadership was a throwback to the style of machine politics that Illinois was famous for in an era when patrons and party connections dominated jobs and construction projects.

support for him cracks started to appear after investigation of Allegation of sexual harassment Details of a federal corruption investigation emerged in late 2019, leading to charges against his staff.

By 2021, Madigan was unable to muster the votes needed to remain speaker. He resigned as a member of the Legislative Committee and as party chairman.

“He was by far the most influential politician in Illinois,” said Constance Mixon, a professor at Elmhurst College. “As governors go and Chicago mayors go, Madigan has been a constant in Illinois politics.”

finding jurors may be difficult

More than 1,000 jury summons were mailed to potential jurors, and the jury pool was narrowed to about 180.

The defense is expected to object because of Madigan’s popularity. Another hurdle is the high level of distrust of politicians in Illinois.

“I don’t know if there’s anyone who hasn’t heard of Michael Madigan,” said defense attorney Gal Pisetzky, who is not involved in the case. “Jury selection is going to be very difficult.”

The trial was postponed for six months as the Supreme Court considers bribery laws at the heart of the case. In June, the country’s high court overturned bribery conviction A former Indiana mayor’s case found that the law criminalizes bribes given before an official act, but not quid pro quos or “gratuities” given afterward.

Madigan’s lawyers argued that the ruling leaves the case against Madigan “constitutionally and otherwise fatally weak,” and asked for many of the charges against him to be dismissed.

But U.S. District Judge John Robert Blakey last week rejected that effort along with a motion to try McClain individually, clearing the way for jury selection to begin in earnest on Wednesday.

Evidence also includes secret recordings

Testimony is expected to last three months. Experts believe the government has a strong case. Defense attorneys will need to refute a wide range of evidence, including wiretaps on Madigan and others.

Madigan’s lawyers are seeking to play a longer version of the conversation, saying the fragments prosecutors want to play lack context.

“The defense has to fight,” Pisetzky said. “It’s very difficult to cross-examine the recordings.”

The timing means the process could extend well beyond the November election and into 2025.

Although Mr. Madigan is no longer in public office, the incident could have an impact on the public’s broader perception of politicians.

“Most members of Congress are not corrupt, but when these high-profile incidents occur, trust is further eroded,” Mixon said. “People are increasingly losing trust in government, becoming more cynical and apathetic.”