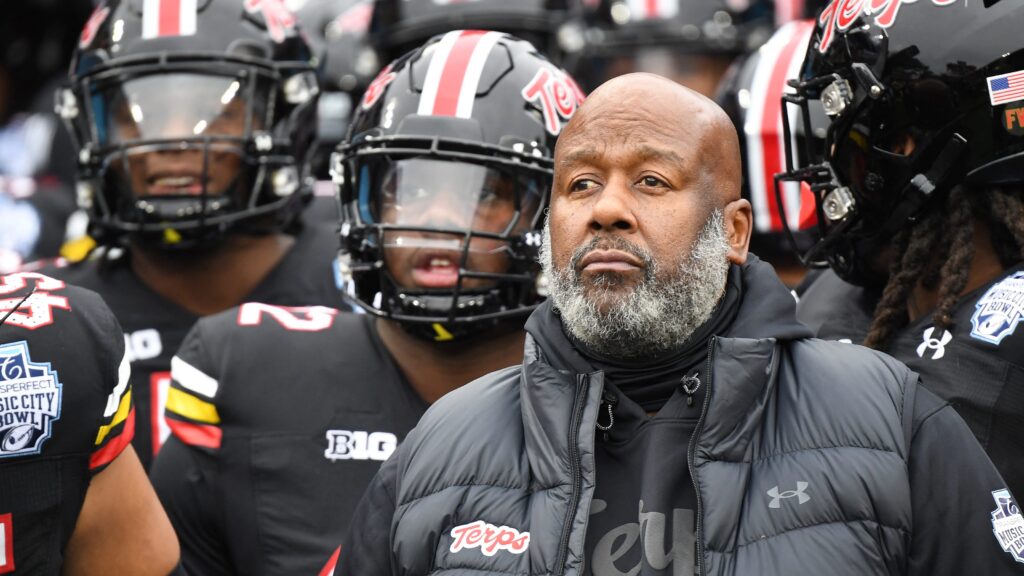

Maryland head football coach Mike Locksley became a strong advocate for athlete mental health after the death of his son in 2017, who was diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder and posthumously diagnosed with CTE. This is the second part of a two-part series on mental health in youth sports, understanding the red flags and how to resolve them. Read part 1 here.

Mike Locksley coached college football at both Illinois and New Mexico State from 2005 to 2011. His son, Meiko, was a star quarterback in high school in both states.

Mayco signed to play at Youngstown State University in Ohio, where he began to change.

He stopped going to class and began having unusual discipline problems. As he moved from school to school, he lost weight, started hallucinating, and seemed to lack the ability to understand speech. He also suffered a concussion while playing in New Mexico, but it wasn’t his first head injury as a longtime soccer player.

Locksley remembers being confused by her son’s actions.

“He has schizophrenia,” Maryland’s head football coach recalled. “He’s calling people who were friends of mine and having these awkward, weird conversations, and they have no clue because he doesn’t have a cast or crutches on his arm.” [like with physical ailments]. ”

It took a lot of learning and reflection to change his thought process. He now advocates and uses that thought process with his own team.

“After a while, I got tired of being sorry and said, ‘What’s so different about ACL?'” My approach was to attack it. To make it look cool. To make it okay. ”

When Locksley spoke at the Project Play Summit in Baltimore in May, he was asked to help the audience understand why mental health advocacy was such an important issue to him.

“It starts with failure,” he says. “I had a son, Mayco Anthony Locksley, who was a Division I football player. … He was dealing with mental health issues before he was killed.”

Mayko was a student at Towson University near Columbia, Maryland, and his father was a coach at the University of Alabama when he was shot and killed in 2017. He was posthumously diagnosed with CTE.

“Mental health has never affected me. I saw my son, who was a normal football player at 21 years old, struggle to understand myth and reality, so now I That was really personal to me.”

“And it just happened. It was just like that for me,” he said, snapping his fingers.

Mr. Locklesy then spoke about its appearance. What he saw in his son’s eyes was something he didn’t recognize at the time.

“You can see the soul of a person in that expression,” Locksley said. Please recognize that. The tragedy of losing my son may have been due to his mental health issues, but it also gave me the opportunity to grow from a boy to a man between the ages of 18 and 22. It gave me the motivation to take care of my children. ”

The audience, filled with coaches and educators, applauded. And so did Mr. Locksley when he mentioned that Maryland had passed a bill requiring the state Department of Education to train public school coaches to certify those accused of mental illness.

Eight states require mental health training for high school coaches, according to a recent study from the University of Connecticut. Another initiative, the Million Coaches Challenge, brought organizations together to train coaches on youth development issues, including mental health.

Meiko’s death taught Locksley to be more conscious of his players’ mental health when coaching. He hopes coaches at all levels will follow his example.

Treating injuries and the player’s mental state

How is it going?

Please tell me what’s going on.

Are you okay?

These are questions you can ask your athlete if something doesn’t seem right. Even if you have no doubts, be proactive.

If you’re recovering from an injury, ask, “How are you feeling after your treatment today?”

Olympic marathoner Clayton Young, who attended a National Athletic Trainers Association mental health briefing last summer, said the tone of an athlete’s voice and reaction to an injury can tell you a lot about an athlete’s mental state. says.

MORE: From hating swimming to winning 10 medals, Allison Schmidt uses her life story to give advice

Young recovered from knee surgery and finished ninth out of more than 70 participants in the men’s marathon at the Paris Olympics. During his rehabilitation, Young recalls the simple act of an athletic trainer texting him in the middle of the night asking about him when he was feeling weak.

It made him feel like someone really cared about him.

“Running is not only my career and the way I make a living with my family, it’s my passion and my identity,” Young said. “You could say this is my medicine. And when you have it all taken away from you as an athlete, it can be very difficult.”

And for major injuries, such as a torn ACL, it could take nine to 12 months to return, said WNBA sports medicine director Marcy Goolsby.

“When you step away from sports, you lose your social network in many ways,” said Goolsby, who also coaches his daughter’s middle school basketball team. “And some sports, like lacrosse and women’s soccer, see more of these injuries, and they can be more damaging and incredibly impactful than others.”

If you are injured, it can be helpful to continue participating in practices and social events with your teammates.

Coach Steve: 5 tips to fully recover from an ACL tear

During his rehab, Young found it uplifting to have a training buddy who was also recovering from an injury. For him, that was Olympian and two-time NCAA cross country champion Connor Mantz.

“We started building this relationship, and at the same time, we inspired each other,” Young said. “We share a lot of struggles and training together. We have a relationship in many areas of life. He is the person who understands me the most. And in running, in the office… , I think everyone should have a Connor Mantz in their life, whether it’s at work or with their family.

Please talk about it. Gain trust.

When a new player or coach joins the Maryland football program, Locksley engages in a practice he calls the “three H’s.” At the end of the practice, everyone shares their greatest moments of happiness, hardship, and heroism.

“That way we get to know them personally,” Locksley said. “And we have an open door policy when it comes to mental health issues. That’s a reality in our program. We talk about it a lot.”

Maylena Hernandez, assistant professor of athletic training at Sam Houston State University in Texas, who sat next to Locksley on stage at the Project Play Summit, spoke about the importance of kids feeling comfortable.

Hernandez conducted a study with athletic trainers and young people from low socio-economic status. She has found that when trainers are good listeners and understand mental health issues, they pick up on emotional cues.

For example, the cross-country runners studied were injured, but why? Athletic trainers were able to determine that their gear was not appropriate. They wore the same torn shoes.

“Or this kid, instead of riding in a new car like the rest of his classmates, he finds himself riding the bus,” she said. “Surprisingly, some of those kids are really good at hiding those things to fit in with their peers. So athletic trainers can actually take advantage of that information and pick up those cues. We can collect these information and determine, “Does this athlete experience these disparities in society compared to other athletes?”

Only about 37% of U.S. high schools have access to full-time athletic trainers, Hernandez said. One initiative in Los Angeles is Team Heal, a hospital community program that helps schools find athletic trainers.

Athletic trainers are another resource for athletes and their families. There is one more person who can watch over him.

“I always talk about that look,” Locksley says. “I know what it looks like right now, but I’m like, ‘What’s going on? How are you doing?

“All these kids want to tell you their problems, but before they open up, you need to build trust and know that you care about them. ”

Steve Borelli, aka Coach Steve, has been an editor and writer for USA TODAY since 1999. He coached his two sons’ baseball and basketball teams for 10 years. He and his wife, Colleen, are now the sports parents of two high school students. His column appears weekly. Click here for his past columns.

(This article has been updated because a previous version contained inaccuracies.)