Getty Images

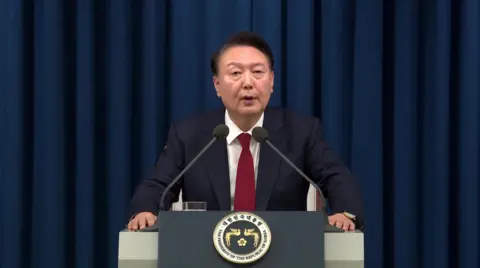

Getty ImagesSouth Korea’s president suddenly declared martial law in the Asian democracy for the first time in nearly 50 years on Tuesday night, shocking the nation.

Yoon Seok-yeol’s bold decision, announced on late-night television, referred to the threat from “anti-national forces” and North Korea.

However, it soon became clear that it was caused not by an external threat, but by his own desperate political problems.

Still, thousands of people rallied in parliament in response to the move, and opposition members rushed to force an emergency vote to repeal the measure.

Defeated, Yun came out hours later to accept the parliamentary vote and lift martial law.

Lawmakers will now vote on whether to impeach him for what the country’s main opposition party called his “acts of rebellion.”

How did it all unfold?

Observers say Yun acted like a president under siege.

In a speech Tuesday night, he detailed the opposition’s attempts to undermine the government and said he would impose martial law to “quell the anti-national forces that are wreaking havoc.”

His decree temporarily put the military in command, with helmeted troops and police deployed to the Capitol and helicopters seen landing on the roof.

Local media also reported that masked troops with guns entered the building as officials tried to stop them with fire extinguishers.

Around 23:00 local time (14:00 Japan time) on Tuesday, the military issued a decree banning protests and activities by parliament and political groups and placing the media under government control.

However, South Korean politicians immediately claimed that Yoon’s declaration was illegal and unconstitutional. The leader of his own political party, the conservative People’s Power Party, also called Yoon’s actions a “wrong move.”

Meanwhile, Lee Jae-myung, leader of the Liberal Democratic Party, the country’s largest opposition party, called on parliamentarians to gather in parliament to reject the declaration.

He also called on ordinary Koreans to attend the National Assembly to protest.

“Tanks, armored personnel carriers, and soldiers with guns and knives will rule this country… Citizens, please come to Congress.”

Thousands heeded the call and rushed to gather outside the heavily guarded Capitol building. Demonstrators chanted “No to martial law!” and “overthrowing the dictatorship.”

Local media broadcast from the scene showed a scuffle between demonstrators and police near the gate. However, despite the military presence, tensions did not escalate to violence.

Lawmakers were also able to bypass barricades and scale fences to get to the polls.

Shortly after 1 a.m. on Wednesday, 190 of the 300 members of South Korea’s parliament rejected the bill. President Yoon’s declaration of martial law was ruled invalid.

Reuters

ReutersHow important is martial law?

Martial law is a temporary state of military authority in times of emergency when civilian authorities are deemed unable to function.

The last time such a declaration was issued in South Korea was in 1979, when the country’s long-time dictator Park Chung-hee was assassinated in a coup.

It has never been invoked since the country became a parliamentary democracy in 1987.

But on Tuesday, Yun pulled the trigger, saying in a national address that he was trying to save South Korea from “anti-national forces.”

Yun, who has taken a significantly tougher stance on North Korea than his predecessor, has described his political opponents as North Korean sympathizers, without providing evidence.

Under martial law, the military is given special powers and, in many cases, civil rights and rule of law standards and protections for citizens are suspended.

Although the military announced restrictions on political activities and media, demonstrators and politicians did not comply with the orders. And there was no sign that the government would take control of the free media, with Yonhap News, state broadcaster and other news outlets continuing to report as usual.

Reuters

ReutersWhy was Mr. Yun feeling pressured?

Yun was elected president in May 2022 as a hard-line conservative, but has been a lame duck president since April when the opposition party won an overwhelming victory in the general election.

Since then, his government has been unable to pass the legislation they wanted, going so far as to veto bills passed by the liberal opposition instead.

He has also been embroiled in several corruption scandals this year, including an incident in which the first lady received a Dior bag and allegations of stock price manipulation, and his approval rating has languished at around 17%.

Just last month, he was forced to apologize on state television after saying he was creating an office to oversee the duties of the first lady. But he rejected a broader investigation that the opposition had called for.

And this week, opposition parties proposed cuts to key government budget proposals that cannot be vetoed.

At the same time, opposition parties also moved to impeach several senior prosecutors, including cabinet members and the head of the Government Audit Agency, for failing to investigate the first lady.

Reuters

Reuters Reuters

ReutersWhat now?

The opposition Democratic Party of Japan moved to impeach Yoon.

Congress has until Saturday to vote on whether to do so.

In South Korea, the impeachment process is relatively simple. For it to become law, it requires support from at least 200 votes, or more than two-thirds of the 300-member Diet.

If the impeachment is approved, the case will be tried by the Constitutional Court, a nine-member council that oversees every branch of South Korea’s government.

If six of the court’s members vote for impeachment, the president will be removed from office.

If this happens, it would not be the first time that a South Korean president has been impeached. In 2016, then-President Park Geun-hye was impeached for aiding and abetting a friend’s blackmail.

In 2004, another president, Roh Moo-hyun, was impeached and suspended for two months. The Constitutional Court subsequently reinstated him to office.

Yun’s thoughtless actions surprised a country that prides itself on being a modern, prosperous democracy that has developed greatly since its dictatorship.

Many see this week’s events as the biggest challenge to that democratic society in decades.

Experts say this could be more damaging to South Korea’s reputation as a democracy than the Jan. 6 riots in the United States.

One of the experts, Leif Eric Easley of Ewha University in Seoul, said, “Yun’s declaration of martial law is both a legal overreach and a political miscalculation, needlessly jeopardizing South Korea’s economy and security. It’s putting us at risk.”

“He sounded like a politician under siege, taking desperate action against growing scandals, institutional obstruction, and calls for impeachment, all of which are now likely to intensify.”