Why would a rational shopper buy a new, certified handbag at a luxury store at full price when parallel importers are selling it for 30 percent less? Luxury goods manufacturers blame China’s economic weakness for sagging sales, but there may be more going on than meets the eye.

China’s “daigou” trade, roughly translated as “purchasing on behalf of others,” is an $81 billion business that specializes in parallel imports of everything from European luxury goods to Korean cosmetics and even high-tech toilet sheets from Japan. Regional price and tax differences mean some products are cheaper to buy outside China, creating arbitrage opportunities.

China is the world’s most expensive major market for luxury goods: Shoppers pay an average of 24% more in a high-end store in Beijing than they would for the exact same item in Paris, according to a Bernstein analysis. The United States is the second most expensive market, with prices increasing by 16%.

Agents scour the world to find the cheapest places to buy luxury goods, then resell them in their home countries at below local prices and claim VAT refunds, increasing their profits.

This parallel market is growing at a much faster pace than China’s luxury industry: Data analytics firm Re-hub analyzed top luxury brands on parallel market platforms such as DeWu and found that proxy sales rose 23% in the first half of this year compared with the same period in 2023. Bernstein luxury analyst Luca Solca estimates that luxury brand sales in China fell 5% on average in the first half of the year.

With cautious Chinese shoppers in a budget-minded mood, the temptation to shop on daigou is strong: A Moncler down jacket can be bought on daigou for about a third less than the retail price, while a Cartier Love ring is sold for an average of 37 percent off the retail price, according to Re-Hub’s analysis.

Luxury brands may have unintentionally driven shoppers into the hands of pro-shoppers by dramatically raising prices in recent years: Prices for luxury goods are up 55% on average compared to 2019, according to HSBC data.

The proxy buying market is becoming more professional. Until a few years ago, students studying abroad would work as proxy buyers on the side to earn some extra cash. They would buy four or five Louis Vuitton handbags in Paris, livestream the purchase, and then ship them to customers in China.

Currently, the market is dominated by corporate traders buying in bulk from links throughout the luxury supply chain. “Buying at European wholesale prices is the best price in the world for luxury goods,” says Chun Lee, an independent luxury consultant.

If a department store has too much inventory at the end of the season, it can sell it to a parallel distributor. Suppose a retailer paid the wholesale price of 400 euros (equivalent to $442) for a luxury handbag that was listed at 1,000 euros but didn’t sell. The parallel distributor might price the bag at 420 to 520 euros as part of a bulk buy, depending on how much demand there is for the luxury item. The department store won’t make as much profit as it would if it had sold the bag to a shopper at full price, but it will still avoid a loss.

Daigo transactions are usually perfectly legal – goods are purchased legally in other markets and, in most cases, import taxes have been paid. But luxury brands have mixed feelings about daigo. Louis Vuitton’s billionaire owner, Bernard Arnault, hates daigo and has tried to prevent parallel selling of his branded goods by effectively banning wholesale. Other brands turn a blind eye, knowingly shipping unsold stock to wholesale clients who resell it to daigo. They don’t like the situation, but not meeting their sales targets is a worse option.

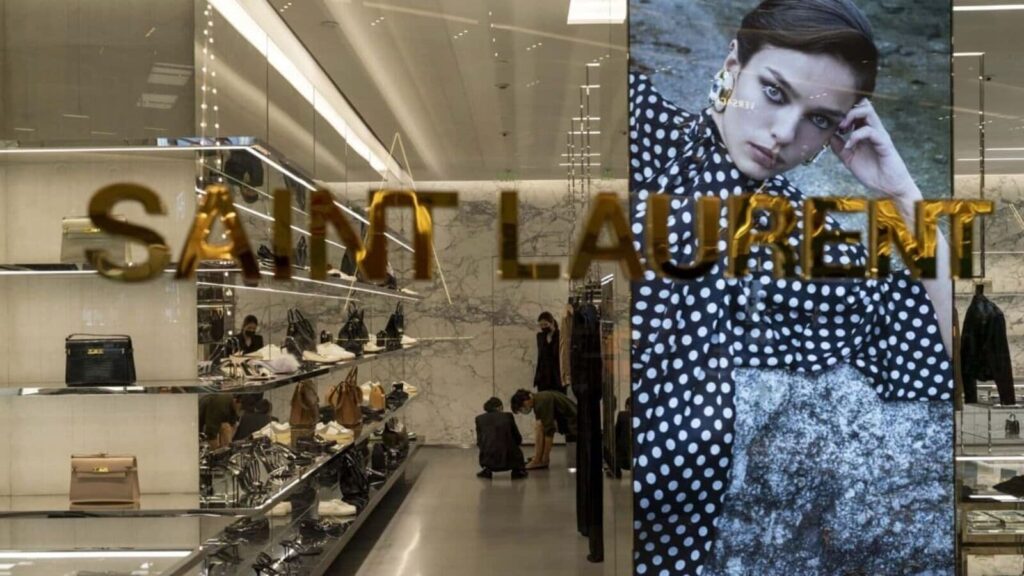

The downside is that pro-shopping undercuts the brands’ regular prices in China. This is even more acute today, as luxury brands poured tens of millions of dollars into new boutiques in China during the pandemic to cater to shoppers who can no longer travel abroad to buy luxury goods. The investments haven’t paid off as well as hoped: While consumers window shop at brands’ flagship stores, pro-shopping agents often pocket the final sales.

Luxury manufacturers could end the arbitrage trade with one stroke by setting the same prices everywhere, but this would create new problems. Lowering prices in China would cut profits and signal to Chinese consumers that their goods are not as valuable as previously thought. Raising prices in Europe is the least harmful option for profits on paper. But local shoppers may not be able to bear another 20% price increase for designer goods.

Thomas Pierchot, head of strategy at Rehab, says luxury executives may be underestimating the behavioral changes taking place on the ground in China: “Brands may tell themselves, ‘Sales are declining because of the economy,’ but there are changes happening that have nothing to do with the economy.”

With luxury inventory in Europe down an average of 24 percent this year, brands need to quickly revive sales in China. Demand for designer goods may actually be higher than it appears in increasingly empty stores. The problem is, it’s agents who are filling the demand.

Write to Carol Ryan at carol.ryan@wsj.com