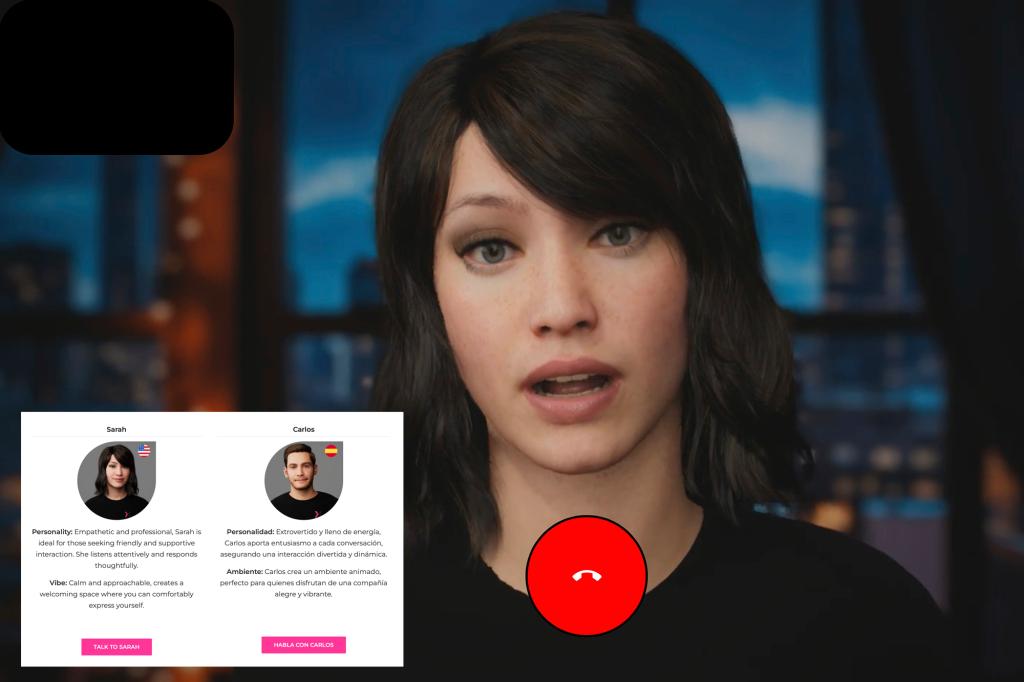

You may receive a call from someone like Anna to schedule your next health check. A friendly voice that will help you prepare for your appointment and answer any pressing questions you may have.

With her calm and warm attitude, Anna was trained to reassure her patients – like many nurses across the United States

But unlike them, she can also chat 24-7 in multiple languages, from Hindi to Haitian Creole.

That’s because ANA is not human, but because it is an artificial intelligence program created by Hippocratic AI, it is one of many new companies offering a way to automate the time-consuming tasks that nurses and medical assistants usually perform.

This is the most visible sign of AI healthcare invasion, with hundreds of hospitals using increasingly sophisticated computer programs to flag patient vital signs, emergency situations and triggering a step-by-step action plan for care.

The hospital says AI is helping nurses work more efficiently while dealing with burnout and staffing shortages. However, nursing unions argue that this poorly understood technique puts nurse expertise first and lowers the quality of patients.

“The hospital was waiting for a moment when something seemed to be justified enough to replace nurses,” said Michelle Mahon of National Nurses United. “The entire ecosystem is designed to automate, skill and ultimately replace caregivers.”

Mahon’s group, the largest nursing coalition in the United States, has organized over 20 demonstrations in hospitals across the country, seeking the right to have a say in how AI is used.

The group issued a new alarm in January when incoming health secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. suggested that AI nurses could help provide care in rural areas as “as good as any doctor.” On Friday, Dr. Mehmet Oz, who was appointed to oversee Medicare and Medicaid, said he believes AI can “release doctors and nurses from all documents.”

Hippocratic AI initially promoted a $9 hour rate for AI assistants, compared to around $40 per hour for registered nurses. Since then, they have tried to drop that language and promote the service instead, ensuring that the customer has been carefully tested. The company did not accept the interview request.

Hospital AI can generate false alarms and dangerous advice

Hospitals have been experimenting with technologies designed to improve care and streamline costs, such as sensors, microphones and motion sensing cameras. Currently, data are linked to electronic medical records and are analysed to predict medical issues and direct nurse care.

Adam Hart worked in the emergency room at Dienity Health in Henderson, Nevada. The hospital’s computer system has flagged new arrival patients due to sepsis, a life-threatening response to infection. Under hospital protocols, he was soon to administer large amounts of IV fluid. However, after further testing, Hart determined that he was treating dialysis patients or people with kidney failure. Such patients should be managed carefully to avoid overloading fluids in the kidneys.

Hart raised concerns with the supervising nurse but was told to follow standard protocols. Only after the intervention by a nearby doctor would patients begin receiving a slow infusion of IV fluid.

“You need to maintain the limit of thinking, which is why you’re paid as a nurse,” Hart said. “It’s reckless and dangerous to carry over the thought process to these devices.”

Hart and other nurses say they understand the goals of AI. It’s about nurses monitoring multiple patients and responding to issues quickly. However, the reality is often a barrage of false alarms, and as an emergency, it can accidentally flag basic physical functions such as patients with intestinal movements.

“You’re trying to focus on your work, but then you’re getting all these distracting alerts that may or may not mean something,” said Melissa Beebe, a cancer nurse at UC Davis Medical Center in Sacramento. “It’s hard to know when it’s accurate and not because of a lot of false alarms.”

Can AI be supported at hospitals?

Michelle Collins, dean of Loyola University’s College of Nursing, says even the most sophisticated techniques miss signs nurses pick up on a daily basis. But people aren’t perfect either.

“It’s stupid to turn your back on this completely,” Collins said. “We should accept what we can do to enhance care, but we also need to be aware that it will not replace the human element.”

More than 100,000 nurses have left the workforce during the Covid-19 pandemic. As the US population and nurses retire, the US government estimates that by 2032 there will be more than 190,000 new openings for nurses each year.

In the face of this trend, hospital administrators will see that AI plays a key role. Rather than taking over care, we help nurses and doctors gather information and communicate with patients.

“Sometimes they talk to humans, and sometimes they don’t.”

At the University of Arkansas Medical Sciences in Little Rock, staff members need to make hundreds of calls each week to prepare patients for surgery. The nurse will review information about prescriptions, heart condition, and other issues such as sleep apnea that need to be carefully reviewed prior to anesthesia.

Problem: Many patients answer calls only in the evening, usually during dinner and during the child’s bedtime.

“So all we need to do is find a way to call hundreds of people into the 120-minute window, but I really don’t want to work overtime with staff to do so,” said Dr. Joseph Sanford, who oversees the center’s health.

Since January, hospitals have used Qventus AI assistants to contact patients and healthcare providers, send and receive medical records, and summarise human staff’s contents. Qventus says 115 hospitals use the technology. It aims to boost hospital revenues with faster surgical transformations, fewer cancellations and fewer burnouts.

Each call begins with the program identifying it as an AI assistant.

“We always want to be completely transparent with our patients, but sometimes we talk to humans, and sometimes we don’t,” Sanford said.

Companies like Qventus offer management services, but other AI developers see a big role in technology.

Israeli startup Xoltar specializes in human-like avatars making video calls with patients. The company is an AI assistant who teaches patients cognitive techniques to manage chronic pain and works with Mayo Clinic. The company is also developing avatars to help smokers quit. According to Xoltar, patients spoke to the program for about 14 minutes, and discussed it with the program.

Nursing professionals studying AI say such programs may work for people who are relatively healthy and active about their own care. But that’s not for most people in the healthcare system.

“We’ve seen a lot of people who have had a lot of trouble with their health,” said Rochelle Fritz of the University of California, Davis School of Nursing.