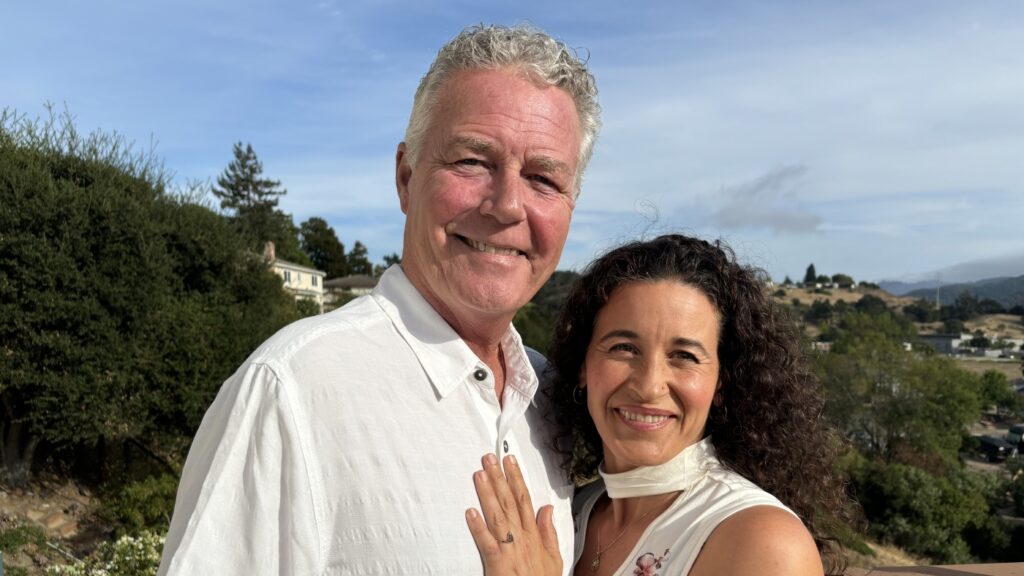

Stephen Ghiglieri and Katrina Vaillancourt at their San Francisco Bay Area home on Sept. 17.

Jude Joffe-Block/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Jude Joffe-Block/NPR

Over the last few years and through this year’s contentious campaign season, which was rooted in America’s deep divisions, there has been a coarsening in the way people talk to each other. We wanted to explore how some are trying to bridge divides. We asked our reporters across the NPR Network to look for examples of people working through their differences. We’re sharing those stories in our series Seeking Common Ground.

Late one night in June 2020, Katrina Vaillancourt lay awake in her bedroom, overwhelmed by the stress of the COVID-19 pandemic. Unable to sleep, she pressed play on an online video series that a friend had sent.

The videos’ narrator promised to reveal “evidence of an elite plan so evil, so all encompassing, that people will be shocked to the core.”

The dizzying 10-part video series was called Fall of the Cabal. It promoted the QAnon conspiracy theory that society is controlled by a satanic cabal that is abusing children. Vaillancourt would later think back on this moment as the point at which her beliefs radically changed overnight, rupturing her closest relationships — including the one with her then-fiancé, Stephen Ghiglieri, who was asleep beside her.

By the next morning, he would have trouble recognizing her.

A match

A mutual friend introduced Ghiglieri and Vaillancourt when they were both in midlife, correctly predicting they would hit it off even though in some ways they are an unlikely pair. Ghiglieri describes himself as “white-collar, Catholic background,” while Vaillancourt jokingly calls herself a “New Age hippie.” He is a silver-haired C-suite executive in the life sciences industry. She is a nonviolent-communication coach with long dark curls. They live in the San Francisco Bay Area together.

Early in their relationship, during the 2016 Democratic presidential primary, they volunteered together for Vaillancourt’s political hero at the time, Bernie Sanders.

Vaillancourt, a natural health enthusiast, has influenced Ghiglieri’s diet and supplement regimen, while he has tried to persuade her of the benefits of modern medicine.

The couple’s differences, however, were exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. They disagreed on the government’s response and vaccines. And things grew tense in the summer of 2020 as they were stuck at home together.

A change overnight

Fall of the Cabal argues that the world is not what it seems and that the media has suppressed the truth. It promotes the baseless claim that an elite group, including well-known Democrats and Hollywood figures, tortures children and consumes a chemical in their blood for its antiaging properties.

As Vaillancourt watched, her initial skepticism gave way to a feeling of devastation. She was relieved when the final episodes claimed a group of government insiders was working on a plan to take down the cabal with then-President Donald Trump’s help. The narrator called the president a “genius, a 5-D chess player, a man with a huge heart.” A “golden age” was on the way.

“I felt nauseated by the sight or the sound of Trump prior to this particular night,” Vaillancourt said. But at a time when the world felt chaotic and uncertain, the message in the series gave her hope. “My fear dissolved,” she recalled. “I felt this beaming of love” and “like the curtain had been thrown wide open.”

Then-President Donald Trump addresses a crowd during a campaign rally on Oct. 24, 2020, in Lumberton, North Carolina.

Melissa Sue Gerrits/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Melissa Sue Gerrits/Getty Images

She stayed up that night trying to fact-check what she had just heard in the videos. Only much later did she realize that her searches were leading her to other QAnon sites.

Ghiglieri had been asleep next to her all night and woke up to find her still on her computer. He was unsettled by her energy. She seemed unfamiliar and frenetic.

As the day progressed, Vaillancourt still was not ready to explain to Ghiglieri the conversion she had just gone through, but after four years together at that point, he could tell something was off.

“I don’t recognize who you are right now,” he recalled telling her. He shocked her when he asked, “You wouldn’t hurt me in my sleep, would you?”

Vaillancourt’s social media feeds kept showing her more and more QAnon content, including posts and videos claiming the alleged cabal had planned the pandemic to institute authoritarian control. “Once you fell into this QAnon rabbit hole, that became the entire online ecosystem,” Vaillancourt said. “My Facebook, my YouTube, my Google searches — everything was giving me more and more of this information that I found so fascinating that I believed myself to be waking up,” she said.

Much of the content appealed to her interest in wellness and alternative health. While some QAnon adherents have promoted hate, antisemitism and violence, Vaillancourt said she did not see content like that.

That first day after watching the series, she shared a post raising questions about the philanthropist Bill Gates’ intentions and the vaccine programs he had funded in the past. Gates has been a frequent target for conspiracy theories. “And on Day 1, I started to have people react to me, argue with me, accuse me of being a racist, sexist, fascist, homophobic, transphobic, crazy, delusional person,” Vaillancourt recalled. “I was like, ‘Where is this coming from?'”

Her old friends began turning their backs on her at a time when she was already feeling isolated due to the pandemic. But at the same time, she met new friends online and was invited to QAnon Facebook groups.

As Ghiglieri heard more about Vaillancourt’s new beliefs, it was hard for him to control his frustration. He said he slammed doors around the house as he wondered, “God, how can she believe this?” Within a few days of watching the video series, Vaillancourt went to stay with a friend.

Finding a path forward

Ghiglieri consulted his therapist, who happened to have experience helping families with members inside cults. His therapist advised he should not expect to be able to change Vaillancourt’s mind and should be prepared that she might never change her views.

Ghiglieri decided to give the relationship six more months. While he hoped she would snap out of it, he was also open to the possibility that they could still make things work even if she didn’t.

He watched Fall of the Cabal and saw why it had affected Vaillancourt so strongly. He knew she had been having a hard time in the months leading up to the moment she pressed play. “And all of a sudden, here is this thing that lays out, ‘Here is the problem, and here’s a solution.'” Ghiglieri said. “And I could see how her sense of idealism — and to some extent some naivete also — but I could see how those were sparked by this.”

Ghiglieri understood he needed to make Vaillancourt feel safe and accepted if he wanted to save the relationship.

“I could say some things that I knew he wouldn’t agree with, and he was willing to say, ‘You know, well, I hear your viewpoint and I don’t share it, but that’s OK,'” Vaillancourt recalled.

Vaillancourt came home a couple of weeks later. Looking back, she said it was key that they rebuilt their connection first rather than start by debating facts.

At one point, Ghiglieri asked Vaillancourt to consider how she would have reacted if he had become a Trump supporter overnight. “I probably would have kicked him out,” she acknowledged. Vaillancourt said it was a wake-up call to remember how difficult this situation was for Ghiglieri.

Ground rules and an off-ramp

As the summer of 2020 progressed, the couple came up with ground rules and boundaries. Ghiglieri pointed out that it wasn’t helpful when Vaillancourt claimed that theories about the satanic cabal were the “truth.”

“It’s a belief,” Ghiglieri recalled saying. “I’ll respect your beliefs, but you can’t tell me it’s the truth. If we can’t see it, touch it, smell it, whatever. It ain’t the truth. It’s a belief.”

Vaillancourt credits her training in nonviolent communication for helping her and Ghiglieri avoid name-calling and dehumanizing each other when they disagreed.

They set times to discuss Vaillancourt’s new beliefs so those beliefs wouldn’t consume them. As she combed through content to show Ghiglieri, Vaillancourt began to doubt some of it or came to realize that some of it was not provable.

As the fall progressed, Vaillancourt gradually backed away from QAnon. “Unfortunately, I didn’t come out near as quickly as I fell in,” she said.

Supporters of then-President Donald Trump fly a U.S. flag together with a QAnon symbol as they gather outside the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C., on Jan. 6, 2021.

Win McNamee/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Win McNamee/Getty Images

She began to realize that QAnon prophecies that were supposed to be imminent, like “the Storm” that would take down the cabal or the return of John F. Kennedy Jr. (the son of President John F. Kennedy who had died in a plane crash in 1999 but who according to QAnon mythology is still alive), had not happened.

Another turning point came when she learned from her father, who is Jewish, that a key tenet of the QAnon conspiracy — that elites are taking children’s blood — borrowed from antisemitic tropes.

“I did not want to be associated with anything that promotes violence,” Vaillancourt said. She said up until that point, she had thought of QAnon only as a peaceful movement and had been convinced “the mainstream media was making up lies about QAnon to try to hide the truth, because they were part of the cabal.”

She said that conversation with her father made her willing to examine “the ways in which calls to violence or hate speech were woven into aspects of QAnon that I wasn’t participating in.”

By the very end of 2020, just over six months after she watched the video series, she decided she was done with QAnon. But she had also grown disillusioned with the Democratic Party in recent years after feeling disappointed in how it ran its presidential primaries. As she searched for what she believed after leaving QAnon, she no longer identified with the left.

“It made me more motivated to step out of polarization and to be both grateful and critical of both sides,” Vaillancourt said, adding that she is now more open to third-party candidates.

QAnon has changed since Vaillancourt discovered it in June 2020. Some social media platforms, especially in the wake of the Jan. 6, 2021, assault on the U.S. Capitol, have taken steps to purge QAnon content. Yet Trump shared posts with QAnon slogans during the 2024 presidential campaign. Billionaire Elon Musk, a Trump ally, recently shared a QAnon meme. Key tenets from QAnon have now permeated right-wing politics, said Mike Rothschild, a journalist who has written extensively about this topic.

“What you have instead is a very mainstream, very-easy-to-buy-into conspiracy movement that holds that there’s a secret war going on between good and evil that is being fought through everything from vaccines for viruses, to DEI (diversity, equity and inclusion), to trans athletes in high school sports, to Israel,” Rothschild said.

Giving others hope

A year after Vaillancourt turned away from QAnon, she and Ghiglieri got married in Maui in December 2021. Their partnership had already “been through the fire,” Ghiglieri said. They had managed to come through this ordeal loving one another. “If we could get through that, we could get through anything,” Vaillancourt said.

Vaillancourt began sharing her story with journalists and researchers, hoping it might help others. Then she decided to write her own book, ReQovery: How I Tumbled Down the QAnon Rabbit Hole and Climbed Out, which came out this year. She and Ghiglieri want to give other families hope that their relationships can also survive.

Vaillancourt said the lessons are relevant beyond QAnon since the Russian government and other foreign governments are trying to spread disinformation with the goal of dividing Americans against each other.

“And it’s working to tear us apart,” Vaillancourt said. “But it doesn’t have to if we can actually remember to choose connection over correction and respect over reaction. We do have a path forward which can heal families without having to agree on everything.”

Katrina Vaillancourt and Stephen Ghiglieri on a honeymoon trip to Maui in 2022 after their wedding there the year before.

Katrina Vaillancourt

hide caption

toggle caption

Katrina Vaillancourt

She and Ghiglieri are still building their path forward. This past election presented new challenges for them to work through.

Ghiglieri says he is struggling with the idea that his fellow Americans reelected Trump and said he feels “resigned to the next four years being potentially very ugly — and that it may not end in four years.”

Vaillancourt voted for Robert F. Kennedy Jr. even though he had dropped out of the race. Trump has picked him to be part of his administration, which she says has given her a reason to feel optimistic.

“I have been of an opinion that’s different than Stephen’s,” she said. “And that’s a difficult thing for me to even say right here. I don’t share the fear that so many people around me do. That’s difficult to acknowledge too.”

In Vaillancourt’s view, voters on both sides of the aisle have more in common than either side recognizes. “Ultimately, what we want is the same thing. And that’s what I wish I could really get across to people.”

As she spoke, Ghiglieri had been turned away from her. “I don’t believe that,” he said as he turned to face her. (Later he clarified that he’s concerned the politicians coming into power don’t want the same things as most Americans.)

These conversations are still raw.

“All I know is I love this man,” Vaillancourt said, as she reached for his arm. “And when we have conversations like this, it stimulates discomfort. And ultimately, every time we come back around and remember how much we love each other.”

About a week later, much of the tension between them had already thawed.

“There are ways to navigate different political beliefs and maintain a happy household,” Ghiglieri said.