Behind the reinforcement door of Court No. 2 at a remote detention center in central Louisiana, an immigrant judge sat alone before he could not communicate.

Dressed in a blue jumpsuit hanging from his slight frame, he was waiting for the court staff to be called three different translation services.

Almost all of the 17 detainees who appeared before Judge Kandra Robbins during the removal lawsuit Tuesday morning, LU had no attorneys as they had no right to legalize US immigration procedures. He sat quietly, clearly confused. Eventually, an alternative interpreter was discovered and began to translate the judge’s questions into mandarins.

“I’m afraid to return to China,” he told the court. He explained how he had already submitted his asylum application after crossing the border to Texas in March 2024. Lu said he was worried that his lawyers had stole his money and didn’t file an asylum claim. Lou, who had just recently been detained, had a hard time understanding as he asked him to list his return country if he was deported.

“Will my order be deleted now?” he asked. “Or should I go to court?”

The judge explained that he was in court and provided him with another application for asylum. His next hearing was scheduled for April.

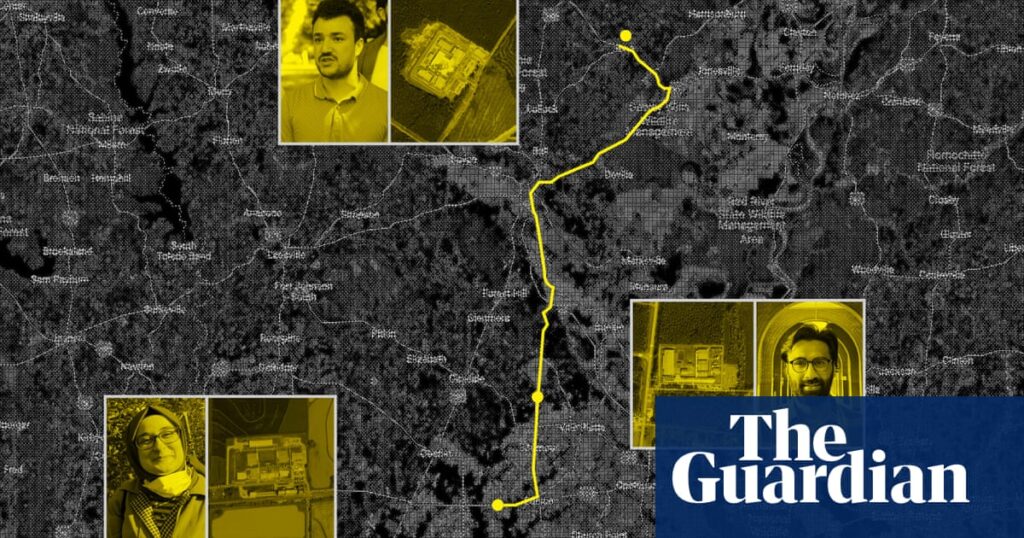

The LaSalle Immigration Court, inside the vast Immigration Customs Enforcement (ICE) Detention Centre in the countryside of Jena, Louisiana, has been in the spotlight in recent weeks after former Columbia graduate student Mahmoud Khalil was moved here earlier this month. His case has attracted international attention as the Trump administration seeks to deport pro-Palestinian activists under rarely used enforcement provisions of US immigration law. The government is fighting fiercely to maintain the Halil case in Louisiana, and he is scheduled to appear again at LaSalle Court on April 8 for removal proceedings.

However, it focuses on a network of remote immigration detention centers spreading between Texas, Louisiana and Mississippi. This is Mississippi, known as “detention centres,” and clusters 14 of the nation’s 20 largest detention centers. And now it’s where other students were sent after being arrested thousands of miles away.

Badar Khan Sri, a research student at Georgetown University, was arrested in Virginia last week and sent to the detention center in Alexandria, Louisiana, and later to Prairieland, another site in eastern Texas. This week, Tufts University doctoral student Rumeysa Ozturk was arrested in Massachusetts and sent to the Southern Louisiana Ice Processing Center in Swampland, Evangeline’s Parish.

These far-off detention facilities and court systems have long been linked to concerns about rights violations, poor treatment and due process. It argues that this will likely only be strengthened during the Trump administration’s crackdown on immigrants, and promises to implement a massive deportation that has led to a surge in the detained population. However, cases within these centres rarely attract the attention of many publics and personal scrutiny.

“Most of the people in Louisiana’s custody aren’t the people who make the news,” said Andrew Perry, an immigration rights lawyer for the Louisiana ACLU. “But they are experiencing similar treatments as people who are, if not the same.”

The Guardian travels to Jena to witness a full day within the LaSalle court, which is rarely visited by journalists, and to observe snapshots of more than 1,100 detainees trapped in a facility where guardians also carry Halil. Dozens of people lined up before the judge for their brief appearances, sworn in mass. Some have expressed severe health concerns, while others are unhappy with the lack of legal representatives. Many had moved from the state hundreds of miles away to the centre.

Early in the morning, Honduras immigrant Wilfredo Espinoza appeared before Judge Robbins for a procedural update to his asylum case, which was scheduled for a full May hearing. Espinoza, who coughed through his appearance and had a small bandage on his face, notified the court, who wanted to abandon his asylum application “for my health.” The circumstances of his detention and timing and the location of his arrest due to ice were not revealed in court.

He suffered from hypertension and fatty liver disease, he said through a Spanish translator. “There were three issues in my mind here,” he said. “I don’t want to be here anymore. I can’t be locked up for this long. I want to leave.”

The judge repeatedly asked him if he was in his own free will decision. “Yes,” he said. “I just want to leave here as soon as possible.”

The judge ordered the removal from the United States.

Proven allegations of medical negligence have plagued Jena’s facilities for many years. In 2018, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) civil rights department investigated the situation of four deaths at the facility. This is run by the GEO Group, a private corrections company. All four deaths occurred between January 2016 and March 2017, with DHS identifying patterns of medical delays citing “nursing staff were unable to report abnormal vital signs.”

At the South Louisiana ICE Processing Center, run by the GEO Group and all women’s facility where Ozturk is currently being held, Louisiana ACLU recently filed a complaint with the Civil Rights Division of DHS, claiming an array of rights violations. These include inadequate access to medical care, with the complaint saying that “security personnel denied access to diagnostic care for detained people suffering from severe conditions such as external bleeding, trembling and sprain branches.”

The complaint was filed in December 2024 before the Trump administration moved to destroy the DHS’ Civil Rights Division earlier this month.

Sign up for This week at Trumpland

A deep dive into the policies, controversy and eccentricity surrounding the Trump administration

Privacy Notice: Newsletters may contain information about charities, online advertising, and content funded by external parties. For more information, please refer to our Privacy Policy. We use Google Recaptcha to protect our website and the application of Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

After the newsletter promotion

A spokesman for Geo Group strongly opposes allegations made regarding services offered at GEO contracted ice processing centres, including Jenna’s facilities.”

“In all cases, our contracted services are monitored by the federal government to ensure strict compliance with applicable federal standards,” the spokesman said it pointed to ICE’s performance-based national detention standards, which states that the company’s contracts are governed.

“These allegations are part of a longstanding politically motivated, radical campaign to abolish ice and end federal immigration detention by attacking federal immigration facility contracts.”

DHS did not respond to multiple requests for comments.

Louisiana experienced a surge in immigrant detention during the first Trump administration. By the end of 2016, the state had the capacity of more than 2,000 immigrant detainees, more than doubled within two years. Institutions previously used as private prisons often opened waves of new ice detention centres in remote rural areas. The state currently holds the second largest number of immigrants detained, after only Texas. As of February 2025, approximately 7,000 people were detained at nine Louisiana facilities, all run by private companies.

“It’s a residential, isolated, ‘invisible, heartless’ place,” said Homelo Lopez, the legal director of Louisiana’s Immigration Services and Legal Advocacy and a former appealed immigration judge. “When it comes to lawyers, families and community support systems, it is difficult to reach people, so for the government it is much easier to present their case.

At LaSalle Court this week, the Guardian observed detainees who have moved from the state, just like Arizona, Florida and Tennessee. At an afternoon hearing when 15 detainees filed for bonds, they released them from detention and transferred the case to a courthouse close to their home, and only two were allowed.

Cases heard from detention are far less likely to provide relief. In Lasalle, 78.6% of cases of asylum are rejected, compared to a national average of 57.7%, according to the TRAC Immigration Data Project. In Robbins Court courts, 52% of asylum seekers appear without a lawyer.

During the afternoon session, the court heard from Fernando Altamarino, a Mexican national who was transferred to Jena from Panama City, Florida, more than 500 miles away. Alta Marino had no criminal history, like almost 50% of immigrants currently in ICE detention. He had been arrested by an agent about a month ago after receiving a traffic ticket following a minor car accident.

He tried to resolve the issue in a local court and instead was taken into custody by immigration authorities. Through his lawyer, the court heard his application for release. A letter from his local church leader described his role as a stubborn member of the congregation and “a person who truly embodies the faith.”

However, DHS prosecutors who opposed everything except one bond application that afternoon claimed that Alta Marino, who had lived in the country for more than a decade, showed flight risks because he was “very limited to nonexistent family ties with the United States.”

The judge agreed as Altamarino stood upright and listened to the translator. Despite his acknowledgement that it was “not dangerous to the community,” she sided with the government and denied the bond.

Altamarino thanked the judge as he left the room under security watch. The heavy door closed behind him as he returned to the void of America’s vast detention system.