Darren Conway/BBC

Darren Conway/BBCSamir el-Chekyeh behind the wheel of an ambulance, sirens blaring, heads towards the latest Israeli airstrikes in el-Karak, in eastern Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley.

The 32-year-old firefighter and paramedic with the Lebanese Civil Defense Force (CDF) could only sleep for a few hours last night. It’s now mid-afternoon and he hasn’t eaten breakfast yet.

Since the escalation of the war between Israel and the Shiite Muslim Hezbollah group, the men and women of the CDF have had little rest, bracing daily for mass casualties.

This article contains a graphical explanation

Samir says it’s completely different from the last war with Israel in 2006. “There were no such airstrikes. Recently, a fire station and a church in the south were attacked and colleagues of humanitarian workers were killed.”

Darren Conway/BBC

Darren Conway/BBCCDF officials say they are seeing an increasing number of civilians, including women and children, being killed or injured while participating in operations.

The war between Israel and Hezbollah is spreading deeper and deeper across Lebanon.

The intense bombing campaign spread far beyond the country’s southern border villages and the capital, Beirut, to the fertile towns of Bekaa and the historic city of Baalbek, centered on the Shiite region where Hezbollah was established. Attacks have also increased in the port cities of Sidon and Tire.

Israel says it is targeting only Hezbollah fighters, weapons and infrastructure. Israel estimates it has destroyed two-thirds of Hezbollah’s rocket and missile stockpile since operations against the militant group intensified.

But Hezbollah continues to fire rockets at Israel every day.

The BBC spent two weeks with members of the Civil Defense in the Bekaa Valley, which stretches east to the border with Syria. Permission from Hezbollah was required to visit Israeli attack sites.

During that time, the number and frequency of strikes in the region increased dramatically.

According to official figures, there were more than 100 Israeli airstrikes on October 28, and 160 people were killed in the Bekaa River last week alone. The Lebanese government does not distinguish between combatants and civilians in its figures.

When Samir and his men arrive at the Shia village of El Karak, the atmosphere is thick with smoke and dust, and chaos and destruction prevail.

Earlier, at the garrison in the nearby city of Saale, they had heard powerful explosions, and from their balconies they could see smoke billowing in the distance. They jumped into a fire truck and an ambulance and headed straight there.

Darren Conway/BBC

Darren Conway/BBCA woman wearing a chador sits on the sidewalk begging to be let into an abandoned, smoky apartment building, but the men persuade her to stay put. It’s too dangerous, and a second Israeli airstrike could come.

The first body they found was that of a man who had been blown to the ground by the explosion.

There are survivors under the pancake floor of the apartment, and Sameer dives deeper into the rubble. Because the fire was still burning inside, they were not wearing protective vinyl gloves, and when they found the child, they could feel the shattered bones beneath their fingertips. When he carefully retrieved the child, he discovered that it was only half full.

“The first victim I found was a child. I don’t know if it was a girl or a boy,” he told me later. “Sorry to explain, but it’s above the stomach – there’s nothing below the stomach.”

In the past, CDF crews have received calls telling them to evacuate the site where they were working. They think they are Israelis. No such call came that day, so Sameer and his team spent an hour digging deeper into the ruins.

Eventually they discover a 10-year-old girl alive. She told rescuers that her 8-month-old brother Mohamed was next to her.

“Then I started hearing small children screaming,” Sameer said.

Through a small gap in the rubble, they found a boy trying to move his legs, the baby’s body, and a blue sock visible to rescue workers. They painstakingly cleared the debris around him, and he was gently held in Sameer’s hands and carried to safety. Mohammed is currently being treated in Iraq for head injuries, his family said.

Darren Conway/BBC

Darren Conway/BBCCDF operates across Lebanon’s sectarian divide. Sameer says he doesn’t discriminate. He is a Christian and is the manager of the station in the city of Saar. Saar is a predominantly Christian town, with a 54-meter-tall statue of the Virgin Mary atop a hill.

“We don’t ask the gender of the victim. We don’t ask if he’s black or white. We don’t ask if he’s Christian or Muslim. We are humanitarians,” Sameer says.

The United Nations estimates that at least one child was killed and 10 injured in Israeli attacks every day in October. These losses, combined with the loss of colleagues killed in the strike, take a heavy toll on Sameer and his men.

Approximately 24 hours after they left the El Karak site, a second Israeli attack destroyed the remainder of the apartment building.

Hezbollah continues to fire rockets at Israeli targets from nearby mountainsides in the evenings. A single salvo of at least six projectiles starts a forest fire near Saar.

In the town of Hodor, a Hezbollah flag is planted on the ruins of one of the many buildings destroyed by Israeli bombing. Children’s toys are lined up at the base. Nearby, a large red Shiite flag flutters in the wind, almost the only sound in the largely abandoned town.

Jawad Hamzeh, his head bandaged, guides me through the rubble of his home.

The attack killed three of her daughters, including 24-year-old Nada, who was pregnant. He holds another daughter’s law book in his hand. She was studying to become a lawyer.

There were no extremists here, he says. “Where are the missiles? Can you see them?” he asks.

Iran-backed Hezbollah launched an attack on Israel on October 8, 2023, in solidarity with its ally Hamas, which had carried out a devastating attack on Israel the day before. After months of cross-border exchanges, Israel assassinated Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah in late September, followed by a ground invasion.

Although Hezbollah is committed to the destruction of Israel, it is not just an extremist group. It is Lebanon’s most powerful political force and a social movement that serves as a bulwark for Lebanon’s long-segregated Shiite community against other sects in the country.

A year of war has left tens of thousands of Israelis displaced. By attacking Hezbollah on multiple fronts, Israel hopes to undermine Hezbollah and force its people to return home.

Despite US-led ceasefire negotiations, neither side seems willing to back down.

On October 30, Israeli forces ordered the evacuation of the city of Bekaa in Baalbek, in what the United Nations described as “the largest forced displacement Lebanon has experienced in a single day” since the start of the conflict. As many as 150,000 people were given just a few hours to escape further Israeli attacks.

Not far from the magnificent Roman ruins of the Temple of Bacchus, I met 42-year-old Hussein Nasseruddin, whose home had been destroyed in an Israeli attack the night before.

“There were no terrorists or bad people living here,” he says. “Everyone who lived here was decent people,” he said, adding that his family, including his own, lived there after fleeing Beirut in 1982 during the civil war. It is said that it was “We were born here, we have lived here, we will remain here and we will not leave,” he says.

As I left, men with pickaxes and shovels were moving slowly through the rubble, and Hussein was preparing to erect a tent in the remains of his home.

Darren Conway/BBC

Darren Conway/BBCAt Dar al-Amal Hospital on the outskirts of the city, the injured are recovering from Baalbek’s worst day. According to the local governor, two-thirds of the 63 people who died were women and children. Israel announced that it had attacked 110 Hezbollah-related targets.

In a bleak room where only screams echo, 3-year-old Selin’s tiny hand reaches out in search of comfort. But there’s no one there. She suffered burns to her face, a broken leg, and wounds to her groin and side. Her mother, father, two sisters, and brother were all killed in an Israeli airstrike, leaving her hurt and alone.

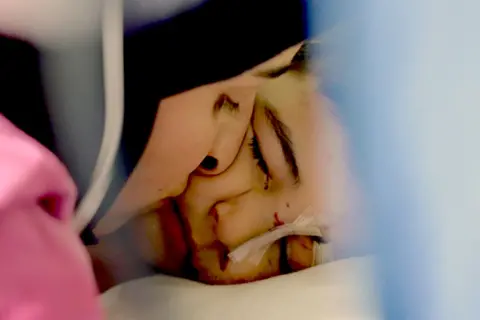

Darren Conway/BBC

Darren Conway/BBCAcross the hallway in the intensive care unit was two-year-old Kayan Smeha, who had suffered a fractured skull. His mother, Najat, 24, kissed him gently on the cheek and hugged him to keep him quiet.

“He’s still panicking,” she told me. “And he’s probably re-running the scene like I was. I can handle it, but he’s so small he can’t.”

Tears roll down her cheeks, but she is defiant.

“I’m crying because I’m scared for my baby. But if they think they can destroy us, they’re wrong. If necessary, I will sacrifice my son, my husband, my father, my mother, my sister.” says Najat.

“The death of a loved one is difficult, but not as difficult as being humiliated. And we will continue to uphold our faith and traditions until the day we die.”

Darren Conway/BBC

Darren Conway/BBCThe sun is rising after a cold night at the small CDF base in the village of Ferzuur, nestled between orchards and vineyards. Seasonal temperatures are dropping here, and most of Lebanon’s shelters for displaced people are full.

Sameer arrived and I asked him how he was dealing with what he saw.

“Some pictures stay in our heads,” he said, adding that they never go away.

He relies heavily on his faith.

“If you can keep one (person) alive, that’s what keeps you going,” he says.

“And this is a God-given power, and we will continue to do our work. Even if we are targeted directly, we are here in Lebanon and God is We say He will protect us, and we believe in Him, and He will protect us.”