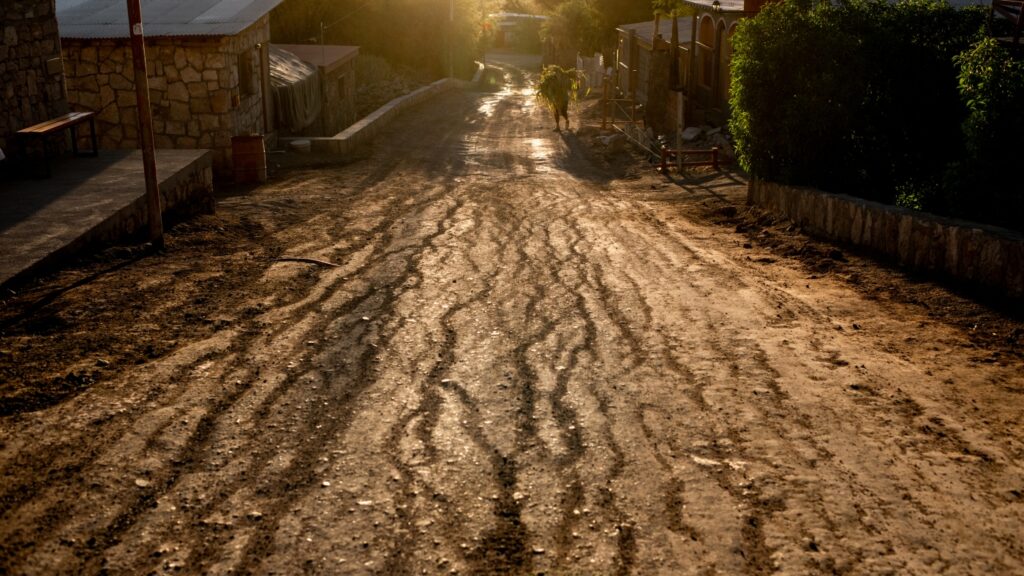

The town of Payne near Shio Flat and one of the closest towns to lithium mining operations. April 13, 2024. Antofagasta, Chile. Cristobal Olivare for NPR Hidden Captions

Toggle caption

Cristobal Olivares of npr

Chile’s Atacama Desert – A black flag bubbles in the wind above the house of Janet Cruz, a hilltop village deep in the Atacama Desert in Chile, on the top of the rugged road in Soar.

The desert sun bleached it into a dark gray blur, but the rebellion it represents remains strong.

On each village home, sparkling in the evening sun, these black flags represent the resistance of Indigenous Likananthai people to lithium mining, which many say is torn apart the community.

The salted lithium beneath the vibrant white atacama salt flats that stretch across the valley floor has become a global resource.

The town of Payne near Shio Flat and one of the closest towns to lithium mining operations. Cristobal Olivare for NPR Hidden Captions

Toggle caption

Cristobal Olivares of npr

It holds the key to the global green energy transition, but the Rikananthai community, who has lived in the area for thousands of years, wonders what they will get themselves.

“Our life is in that water,” says Cruz. “On a dry day, we’re dead as a culture and we have to leave.”

“They can give us all the money and resources they want, but they will never regain what we have lost.”

Before refinement, lithium-rich salt water is pumped onto the surface to mix with groundwater, then slowly move between the pool of turquoise on the evaporated salt flat surface.

The concentrated lithium carbonate salt is powered by a fantastic convoy of trucks to the city of Antofagasta on the coast, where it is purified and exported, turned into batteries, and entered into cell phones and electric vehicles.

Currently, three companies are setting up Atacama Salt Flat operations.

The former wetland, Tiropozo, was dried, according to Paine residents due to water extraction by the lithium company. Saturday, April 13th, 2024. Antofagasta, Chile. Cristobal Olivare for NPR Hidden Captions

Toggle caption

Cristobal Olivares of npr

SQM, a Chilean chemical company, has been operating there since the 1980s. US-based Albemarle Corp. has made concessions since 2015, with China’s biggest electric power company BYD in its latest operation.

All three have rental agreements with Chilean national development agency Corfo, through which money is being spent for “sustainable development of the community.”

“What I saw in the area is that you can work in each community, at least in some way. Around the Atacama Salt Flat for three years.

“We believe that awareness is improving, but we are always finding a wide range of opinions.”

As part of its contract with CORFO, SQM shares $15 million a year equally among 19 communities in the area. Additional payments will be made depending on factors such as population and distance from mining operations.

SQM has agreed with five communities working on healthcare, education, culture and infrastructure projects.

Meanwhile, residents of Payne’s town at the far end of Salt Flat say they have agreed with Albemarle since 2012. A portion of the money was spent building a new soccer field at the foot of the town. .

A soccer court paid by lithium companies in the Indigenous community of Payne, the town closest to lithium mining work at Atacama Salt Flat on Saturday, April 12, 2024. Cristobal Olivare for NPR Hidden Captions

Toggle caption

Cristobal Olivares of npr

BYD declined to request a comment.

According to the US Geological Survey, Chile is the world’s second largest producer of lithium and has the largest known reserves of minerals.

However, there is little consensus among locals about what to do with the lithium boom revenue.

Some communities around Salt Flat are accepting direct compensation from businesses. Others assert that the damages being inflicted are irreparable and cannot be offset by payment.

“Lithium will never last forever,” sighs Sara Plaza, 72, a lifelong resident of Pine. “The next generation has no water, no work, none. Nothing.”

“It’s the richness of the culture and community spirit. It’s not like it was before, it’s not like it was before. I’m not looking at such a bright future anymore.”

On the plains are sharp and sharp like slender clusters of grass that creep out between them, with sharp crusts of salty rock razors loosening in the sky like frozen waves.

The Plaza walks completely easily through the rough ground, pointing to places above or just above the uncharacteristic horizon that are not apparent to foreign eyes.

Sara Plaza members of Payne’s Indigenous Community are walking nearby the water extraction of former wetland Tilopozo. Cristobal Olivare for NPR Hidden Captions

Toggle caption

Cristobal Olivares of npr

Members of the Indigenous community at Sarah Plaza (72) Payne stand in Tiropozo, a former wetland, according to Payne residents, who have been dried for water extraction by lithium companies. Saturday, April 13th, 2024. Antofagasta, Chile. Cristobal Olivare for NPR Hidden Captions

Toggle caption

Cristobal Olivares of npr

She remembers where the animals graze. I remember people in Licanantei swimming and covering their skin with thick mud to relieve joint pain. Others will come down to hunt flamingo eggs, but few birds will visit these parts anymore, says Plaza.

As she speaks, the tanker pulls up to pour diesel into a generator that drives a water pump that extracts hundreds of liters of water per second from the wetland areas where animals once began grazing and swimming.

A recent study conducted by scientists at the University of Chile has shown that mining groundwater extraction was associated with the collapse of Atacama salt flats.

However, the exploitation of salt flats is set to increase even more.

The former wetland, Tiropozo, was dried, according to Paine residents due to water extraction by the lithium company. Cristobal Olivare for NPR Hidden Captions

Toggle caption

Cristobal Olivares of npr

Starting in January 2031, a public-private partnership will take over the lithium contract, with national copper mining company Codelco holding a majority share and Chile will be the majority shareholder.

“This is an unprecedented step for Chilean mining,” said then President Gabriel Borik, a public-private partnership.

“You can’t repeat the same equations from the past,” Borick said. “In addition to collecting revenue, we also need to be involved in the entire process of extracting, producing and generating value-added lithium products.”

However, many residents in the area disagree.

“There is already an extractive interest-oriented mentality in our community,” says Rosa Ramoscork, an activist from the Liccanantei town of San Pedro de Takama, who works in ecotourism. “Social and cultural fabrics are already broken.”

And at the other end of Paine’s salt flat, activist Sergio Kubilos calls attention.

“We don’t know enough about how the effects (of further extraction) affect the Atacama salt flats, or whether the local hydrology fits the national lithium strategy,” he says. Masu.

Sara Plaza members of Payne’s Indigenous Community will be working on her farm on Saturday, April 13, 2024.

Toggle caption

Cristobal Olivares of npr

Every night, Paine’s narrow, cracked Earth Street becomes a racetrack for contractors’ vehicles that thunder to the top of the town.

Cubillos says there was friction in the town as more people arrived to work in the lithium industry, increasing Payne’s resources and increasing rental value.

There have even been a handful of trucks being stolen, and people have begun to put security fences outside their homes. The silence faded from the Paine, he says.

“We were able to disappear very easily,” Cubillos sadly says, as he sat in a small park funded by a contract with one of the mining companies. Masu.

“This is horror and I think we all share it. Very simply, our culture can no longer exist.”