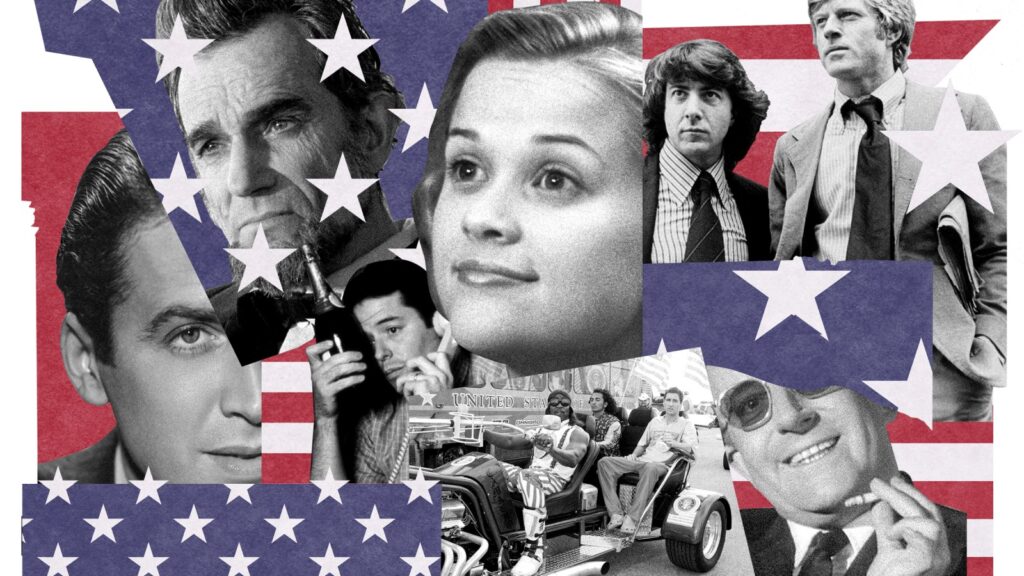

From Idiocracy to All the President’s Men, our picks for the funniest, most frightening, and flat-out greatest movies on the American political process

Perhaps you’ve heard there’s a presidential election coming up? One that may, in fact, be the single most important referendum on our way of government in our lifetime? It is a reality that may have you looking for inspiration in the final weeks leading up to Nov. 5 — or escape. How better to thread this particular needle than with movies about American politics? Filmmakers have long been dealing with the topic of our nation’s origin story, and how our particular manner of governance — “by the people, for the people,” or at least that’s how it reads on the page — has contributed to the idealistic image of America that its citizens hold near and dear to our hearts. But well before Watergate became more than just a hotel, the movies have also cast a keen kino-eye on how American democracy is a notion that’s ideal in conception and too often flawed in execution. Here are our picks for the 20 best films exploring the good, the bad, and the extremely ugly aspects of American politics.

‘Bulworth’ (1998)

A devastating critique of Clinton-era triangulation that is very much a product of that era’s ugly race politics, Bulworth is a hilarious satire and paranoid fever dream from start to finish. Warren Beatty co-wrote, directed, and stars as Jay Bulworth, a corrupt California Democratic senator who, after a bad bet, demands a $10 million life insurance policy from an insurance lobbyist to do the industry’s bidding, before taking out a contract on his own life. As he loses his mind, Bulworth begins to tell many truths about American politics and corporate capture, while rapping awkwardly and fighting to stay alive. It’s not a perfect film, but it goes hard. —Andrew Perez

‘Secret Honor’ (1984)

When it debuted onstage, this one-man production was subtitled The Last Testament of Richard M. Nixon. But in the film version, viscerally directed by Robert Altman, our 37th president really lets it blurt over the course of a profanity-laden, 90-minute monologue. Set entirely in his study in the late 1970s, the disgraced Tricky Dick spends an anguished evening wrestling with the demons in his head, drowning in anger, self-pity, and booze. Philip Baker Hall was a relative unknown at the time, but the casting was perfect: He doesn’t resemble Nixon so much as he harnesses the man’s scalding contempt and crippling insecurity, his every word a blunt rejoinder to invisible enemies who have long since vanquished him. Secret Honor is a fictionalized spin on one of this nation’s most ruinous leaders, and this claustrophobic, stripped-down drama resists humanizing a monster. Rather, it gives Nixon enough begrudging respect to allow him to be unrepentant to the bitter end, turning his final, looped “Fuck ‘em!” into one last cry of rage into the abyss. —Tim Grierson

‘Primary Colors’ (1998)

Anyone still harboring nostalgia for the Clinton years would do well to revisit this complicated, nuanced drama starring John Travolta as the Bill-like Jack Stanton, a deeply flawed Southern governor running for president. Sure, he’s charming and handsome, but he’s also awfully oily — and he sure seems to have an issue being faithful to his wife Susan (a delightfully crisp Emma Thompson). Based on Joe Klein’s fictionalized account of the 1992 presidential campaign, Primary Colors stands as a fascinating time capsule of late-20th-century politics, a now-quaint bygone era before George W. Bush, 9/11, the Iraq War, and Donald Trump profoundly coarsened our discourse and made Clinton’s indiscretions, by comparison, seem relatively minor. Directed by Mike Nichols and written by his longtime creative partner Elaine May, this tart film has no illusions about the duplicity and cynicism of Clinton’s time. Pity those qualities have only gotten worse in our politics since he left office. —T.G.

‘Milk’ (2008)

Sean Penn’s Oscar-winning — and eerily precise — performance as title character Harvey Milk, the first gay man elected to public office in California, to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, is largely the selling point of Gus Van Sant’s biopic. But Milk itself is a deeper work than that. The shadow of the supervisor’s murder hangs over the film, which opens with him recording a tape to be played in the event of his death, a tragedy we know eventually comes at the hands of fellow board member Dan White, played with barely concealed internal turmoil by Josh Brolin. Van Sant captures the two poles of Milk’s life: the euphoria of his election, a result of his genuinely galvanizing persona, and the fear that follows him as soon as he achieves his goal. —Esther Zuckerman

‘Dick’ (1999)

Every journalist loves All the President’s Men — who doesn’t aspire to break open a story that takes down a sitting president? The movie Dick asks the question: What if it wasn’t dogged reporting and following the money that unearthed the Watergate scandal, but a story that’s far more embarrassing? Kirsten Dunst and Michelle Williams play two teens who stumble into the crime, every step of the way, and together serve as Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein’s main sources under the pseudonym “Deep Throat.” It’s a great spoof, and a reminder, for anyone in the media who needs it, not to take ourselves too seriously. —A.P.

‘The Best Man’ (1964)

Gore Vidal — a gent who was no stranger to political dynasties and how the Beltway’s sausage got made — here adapted his own play, in which two all-too-human candidates claw their way toward their party’s nomination for the presidency. Henry Fonda plays William Russell, the former Secretary of State who hopes his mental and marital problems aren’t road blocks to nabbing partisan support. Cliff Robertson is Joe Cantwell, a senator with a knack for turning his strident anti-communist rants into a viable populist platform. (Any resemblance to a real-life congressmen is not the least bit coincidental.) Both men find themselves in the possession of damning material surrounding the other’s past — specifically, reports on Russell’s psychological profile and someone willing to confirm rumors of Cantwell’s “indecent” relations while serving in the military. The question soon becomes whether it’s moral or not to use such unsavory information to one’s advantage. Just think: Once upon a time, ethics in politics was actually a thing. —David Fear

‘All the King’s Men’ (1949)

Based not-so-loosely on the life and career of Louisiana governor Huey Long, Robert Warren Penn’s book was viewed by Hollywood as potential Oscar fodder even before it had won the Pulitzer — the fact that Robert Rossen’s prestigious screen version ended up garnering seven Academy Award nominations and winning three (including Best Picture) essentially secured its place in the political-drama canon. But even if you take all of the accolades out of the picture, this movie is still a great example of how everything from private-interest power brokers to dirty-tricks experts to the media apparatus can conspire to make (or break) a political figurehead. And Broderick Crawford’s theatrical, gloriously over-the-top Willie Stark now reminds you of every political bigwig, Southern or otherwise, who’s exploited their “man of the people” persona for extremely personal gain. —D.F.

‘Being There’ (1979)

Hal Ashby’s adaptation of author Jerzy Kosiński’s novel about a mentally challenged man whose Zen naiveté becomes a kind of spiritual Rorschach for a society adrift in its own glazed complacency was a note-perfect late-Seventies satire. Played with a soothing sense of sublime absence by Peter Sellers, the film’s hero, Chauncey Gardener, goes from wandering the streets to meandering the halls of power, becoming a political insider based on nothing more than his vague WASP-ish aspect and his unintended genius for winning people over (including the President of the United States) by saying — and essentially being — nothing. Lulling its audience into opaque amusement rather than grabbing it by the lapels, Being There has an eerie sense of serenity for a political film, a still-water reflection of an America all too content to give up on giving on a shit and cynically sleepwalk through history. —Jon Dolan

‘Advise and Consent’ (1962)

When the Secretary of State unexpectedly dies, the president puts forth his political ally Robert Leffingwell as a replacement. Given that no less than Tom Joad himself, a.k.a. Henry Fonda, is portraying this potential new member of the administration, you’d think the job would be his to turn down. Except Leffingwell has made an exceptional number of enemies in Congress over the years and “has never played ball… not even the most ordinary, political-courtesy kind of ball!” Cue various factions of the Senate using their powers — see title — to make sure he never gets past the nomination phase. Most folks remember Otto Preminger’s adaptation of Allen Drury’s bestseller as being one of the first Hollywood movies to show a gay bar onscreen. But the director also managed to shoot sequences inside the actual Capitol, a rarity that added verisimilitude to what’s really an all-star Beltway version of Peyton Place. Even in the early 1960s, the backstabbing and bipartisan brawling was simply viewed as business as usual. —D.F.

‘Election’ (1999)

A mere 13 years after Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, Matthew Broderick returned to the cutthroat world of high school for Alexander Payne’s Election. This time around, he’s Jim McAllister, an emasculated history and civics teacher overseeing a student-government election contest between a dimwitted jock, Paul Metzler (Chris Klein), and an ambitious overachiever in Tracy Flick (Reese Witherspoon). Near the end, he rigs the election in Metzler’s favor — and destroys his own life in the process. Payne saw the movie as a microcosm of politics in America, but he had no idea it would launch 10,000 opinion pieces comparing Hillary Clinton to Tracy Flick (often unfairly), or that stolen election claims would soon become a standard part of political life in the 21st century. If you haven’t seen the movie recently, watch it again. Flick isn’t the villain that many of us recall; she’s a flawed hero. McAllister, however, is a monster. —Andy Greene

‘A Face in the Crowd’ (1957)

It’d be great if we could cordon off Ellia Kazan’s depiction of homegrown populist demagoguery as a brilliant relic of the McCarthy era, but A Face in the Crowd remains scarily prescient almost seven decades after it came out. Then-newcomer Andy Griffith plays a singing, guitar-slinging, rapaciously charming Arkansas drifter who is discovered by Patricia Neal’s enterprising publicist, dubbed Lonesome Rhodes, and catapulted into national fame — first as a pitchman for a mattress company and a cure-all called Vitajex, then as a hugely popular TV host dispensing folky bromides, and finally as a crypto-fascist political rabble rouser barreling toward his own horrific unmasking. Lonesome’s natural connection with the people is only exceeded by his seething contempt for them: “They think like I do, but they’re even more stupid than I am, so I gotta think for ‘em,” he proclaims. Griffth’s embodiment of that hypocrisy — in his shifts from the cornpone exuberance of his character’s public persona to the maniacal glee of the increasingly unhinged villain he becomes behind-the-scenes — is as troubling as it is captivating, especially if you grew up watching him as the lovable, reassuring TV sheriff on reruns of The Andy Griffith Show. The result might be the greatest “Could it happen here?” cautionary tale ever put onscreen. Spoiler: In 2016, it did. —J.D.

‘Bob Roberts’ (1992)

This satirical mockumentary may well have predicted both the political rise of Donald Trump and the music of Oliver Anthony. Tim Robbins wrote, directed, and stars in Bob Roberts as the title character, a wealthy Pennsylvania Senate candidate who serves up overt right-wing dog whistles as folk songs. Roberts is a master manipulator, willing to do anything to get ahead. Sound familiar? After Trump won in 2016, Robbins acknowledged that “Bob Roberts came true.” He wasn’t comfortable with comparisons between his movie and real life after a gunman shot Trump at a rally, injuring his ear — but when you’ve made a film as scathing and prescient as this one, people remember. —A.P.

‘Lincoln’ (2012)

Cramming the entire saga of Abraham Lincoln’s life into a single movie isn’t even remotely possible. That’s why Steven Spielberg and screenwriter Tony Kushner wisely zoomed in tightly on January 1865, when Lincoln, played by Daniel Day-Lewis, is trying to push the 13th amendment through the House of Representatives. It was a critical moment that would bring about the end of slavery in America, and it required quite a bit of bribing and cajoling from Honest Abe and his associates. The film is a gritty look at how politics is practiced in America, one that rings just as true today as it did 160 years ago. And with apologies to Henry Fonda, Daniel Day-Lewis is the greatest Lincoln in Hollywood history. —A.G.

‘Idiocracy’ (1999)

For the first few years after its release in 2006, it was easy to dismiss this Mike Judge movie as a wild satire — especially the part about former brain-dead professional wrestler Dwayne Elizondo Mountain Dew Herbert Camacho becoming the President of the United States. It turned out to be one of the most prophetic movies in Hollywood history when Donald Trump, a proud member of the WWE Hall of Fame, took that same oath of office a little over a decade later. “I know shit’s bad right now,” President Camacho tells Congress midway through the movie, “with all that starving bullshit, and the dust storms, and we are running out of French fries and burrito coverings. But I got a solution.” We were lucky enough to preserve our French fries and burrito coverings during Trump’s first term. Another time around, we might not be so lucky. —A.G.

‘Wag the Dog’ (1997)

A master of media manipulation (Robert DeNiro) taps a Hollywood producer (Dustin Hoffman) to help him manufacture an international crisis with enough juice to distract from news that the President of the United States propositioned a Girl Scout in the Oval Office 11 days out from the election. This plot would have sounded far-fetched when it was released in December 1997 — for about a month, at least, until news broke that Bill Clinton had been conducting an affair with a White House intern. (His administration later went on to bomb a pharmaceutical plant in Sudan, drawing criticism that he was trying to pull a “wag the dog.”) Hoffman’s Stanley Motss throws himself into the assignment, hiring a young ingénue (Kirsten Dunst) to play a refugee escaping her burning village, cradling a bag of Tostitos, in front of a green screen (the chips would be subbed out for a kitten in postproduction), among other strokes of brilliance. Motss is ultimately undone, of course, by his burning desire for public recognition of the work he did duping millions of voters into re-electing the guy. (He complains at one point that there is no Academy Award for producing — apparently collecting for Best Picture isn’t credit enough!) Decades later, the cynical send-up of both D.C.’s political operators and the gullible masses they influence not only retains its charm, it feels relevant as ever. —Tessa Stuart

‘Mr. Smith Goes to Washington’ (1939)

Frank Capra often made movies about idealists: “Most of these heroes have faith… Faith in goodness and in the innate goodness of human beings. They lived that and they believed it.” The Oscar-winning director found the perfect vessel for such optimism in James Stewart, who played Jefferson Smith, the prototypical small-town dreamer who becomes a U.S. senator, discovering to his dismay just how corrupt Washington politicians are. Condemned at the time by some for supposedly being anti-American, this patriotic classic remains prescient about the limitations of idealism when facing a broken system in which business interests and the elite conspire to keep the sort of change Mr. Smith proposes from happening. And for those quick to dismiss Capra’s humanist dramas as corny, look how much Smith’s faith and decency are challenged — such a principled stand is so stirring precisely because it is so staunchly tested. —T.G.

‘The Candidate’ (1972)

Can politics destroy a person’s soul? We know the answer to that now, of course, but when director Michael Richie’s satire came out in 1972, the idea was revelatory. Robert Redford, looking as gorgeously camera-ready as ever, plays Bill McKay, a lawyer who happens to be the son of a former governor. The wily campaign strategist Marvin Lucas (Peter Boyle) sees Bill as a perfect candidate to run against an incumbent Republican Senator. He’s handsome and genuine — just the kind of person who can unseat the tired, fusty opponent. As the campaign drags on, you can see the life seeping out of him, and though McKay still acts the part well, it turns out to be just that: acting. The prescience of this clear-eyed look at where politics was headed can’t be overstated. Back when people assumed we could trust the people in office, The Candidate proved it’s all a machine. —E.Z.

‘Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned How to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb’ (1964)

Stanley Kubrick had originally planned on doing a dead-serious take on the threat of nuclear annihilation (and should you crave that, we highly recommend Sidney Lumet’s Fail Safe, an equally great political movie released later that same year). Instead, he and screenwriter Terry Southern pivoted to the absurdity of a U.S.-USSR endgame of mutually assured destruction, and produced what may the ultimate black comedy. How else to describe a film that soundtracks our species’ self-destructive demise with the ironically cheery “We’ll Meet Again”? Everyone remembers Peter Sellers’ bizarro take on the title character, a former Nazi scientist spitting out mass death stats when he’s not fighting with his own mechanical hand. What sticks out now is the second of his three performances here, in which he plays President Merkin Muffley, a liberal-leaning commander-in-chief (based loosely on Democratic candidate Adlai Stevenson). His one-sided conversation with the Russian premier only enhances the idea that even the most powerful leaders are powerless when the clock strikes Armageddon time. And he comes off better than his fellow politicians, foreign bureaucrats, and military wackadoos, all of whom are either complete boobs or the sort of petty, combative cretins that inspire what remains a pitch-perfect punchline: “Gentlemen, you can’t fight in here — this is a War Room!” —D.F.

‘In the Loop’ (2009)

When the first line of a movie is, “Morning, my little chicks and cocks,” don’t say you weren’t warned. Armando Iannucci’s profane political satire is far more than a dress rehearsal for his later project Veep — though the two share faux-vérité cinematography and biting insults. (A highly incomplete sampling of nicknames from this film: “Young Lankenstein,” “Abattoir of room meat,” “Leaky Mingebox,” and “Scary little poodle-fucker.”) Set amid the run-up to a possible war pitting the U.S. and England against an unnamed enemy, “there are very few redeeming characters in it,” Iannucci said upon its release. Even that’s an understatement. A State department higher-up doctors an official government transcript, visiting British politicians discuss being too afraid to masturbate in the nation’s capital, and “ram it up the shitter with a lubricated horse cock” is an acceptable, if not encouraged, way to talk to your co-workers. Even if political humor isn’t your bag, hearing a Scottish press officer call opera “Subsidized! Foreign! Fucking! Vowels!” — one of many insults hurled with the speed of a fastball and the twist of a screwball — is worth it alone. Fuckity-bye! —Jason Newman

‘All the President’s Men’ (1976)

A great newspaper drama and an even better political thriller, this Oscar winner turned recent history into an electrifying and reassuring motion picture about the durability of America’s foundational institutions. No one who saw this adaptation of journalists Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward’s book had any doubt about the ending — we already knew those dogged Washington Post reporters were going to connect the Watergate break-in to Richard Nixon, who would resign the presidency — and yet the movie couldn’t be more gripping. Perhaps it was because director Alan J. Pakula and screenwriter William Goldman imagined the film as a taut procedural, in which Dustin Hoffman and Robert Redford are the grouchy, unconventional buddy-cop duo who’ll pound the pavement trying to find sources willing to go on the record. Maybe it was because the cast was filled with a murderers’ row of incredible character actors, including Jason Robards, who took home a Best Supporting Actor Oscar as eternally stern Post editor Ben Bradlee. Or maybe it was because everyone involved managed to perfectly balance the story’s mixture of patriotic fervor and stripped-down professionalism, viewing the Watergate cover-up as an urgent crisis that challenged the very principles of our democracy. Those alarm bells have not diminished in the nearly 50 years since the film’s release — if anything, the crisis feels even more present and harrowing now than it did then. Perhaps that’s why so many of us return to All the President’s Men: We want to be reminded that, eventually, justice will prevail and the bad guys will be taken down. Sometimes, that hope is all we have. —T.G.