NHANES (1999–2018) data from 5163 individuals were enrolled in the final analysis (Additional file 1: Fig. S1). A total of 101,316 persons ≥ 1 year of age who participated in the in-person or in-home interview and 96,153 were excluded, as follows: (1) 46 235 participants < 20 years of age; (2) 49,915 whom were not diagnosed with cancer, and (3) 3 individuals who did not have unique identifiers to allow linkage to the National Death Index. Of the 5163 cancer survivors (weighted population, 32,623 176; 57.7% female) in this study cohort, 3580 (69.3%) were NHW, 631 (12.2%) were Hispanic, 718 (13.9%) were NHB, and 234 (4.5%) individuals of were classified as race and ethnicity, including American Indian/native Alaskan, Pacific Islander, Asian, and multiracial (Table 1). Compared to NHW, Hispanic, NHB and other race and ethnic cancer survivors were more likely to have unfavorable SDoH factors, including not being married nor living with a partner, education less than high school, a PIR < 2.4, renting a home or other arrangement, unemployment, government or none health insurance, and marginal, low, or very low security. However, a lower proportion of NHB participants had no place routine place when sick or in need of advice about healthcare compared with cancer survivors from all other racial and ethnic subgroups. Approximately 24.9% of cancer survivors did not have a cumulative number of unfavorable SDoH. The higher proportion of NHW cancer survivors with 0 and 1 cumulative unfavorable SDoH was observed compared to patients from all other race and ethnic subgroups. In addition, a higher proportion of Hispanic cancer survivors with 3, 4, 5, and 6 or more unfavorable SDoH was observed compared to patients from all other race and ethnic subgroups. NHB and Hispanic individuals had a higher prevalence of multiple unfavorable SDoH (cumulative of 3 or more) compared to NHW cancer survivors.

Table 1 Sample sizea and characteristics for US cancer survivors age 20 years and older, NHANES 1999 to 2018

Then, we analyzed the relationship between the eight SDoH variables. The results showed that all eight SDoH variables were significantly correlated with each other (Additional file 1: Fig. S2). Furthermore, the proportion of male participants decreased stepwise from 34.8% (0 unfavorable SDoH) to 2.2% (6 or more number of unfavorable SDoH), whereas the proportion of female participants increased from 22.6% (0 unfavorable SDoH) to 24.8% (1 unfavorable SDoH), and then gradually decreased to 4.7% (6 or more number of unfavorable SDoH; Additional file 1: Fig. S3). Breast and prostate cancer were the most common malignant neoplasm type in males and females, respectively (Additional file 1: Table S3).

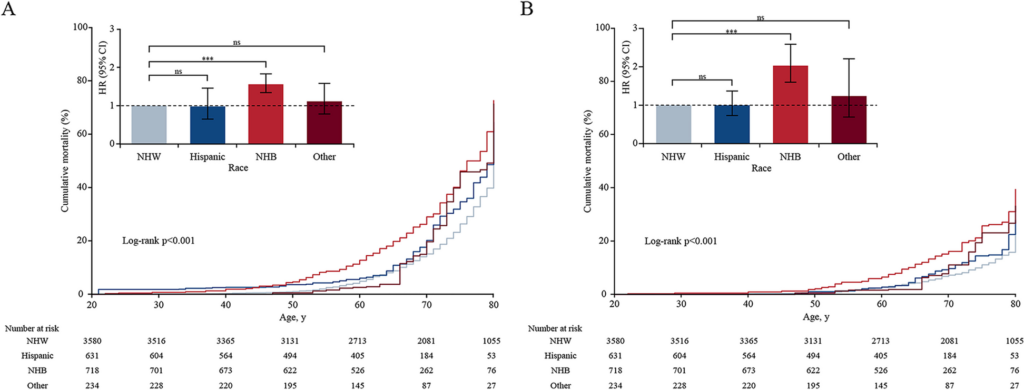

During the median follow-up of 81 months (ranged 0–249 months) in the 10 NHANES cycles linked mortality file cohort, a total of 1964 deaths occurred (all-cause), including 624 cancer patients who died from cancer (cancer-related mortality), 529 who died from cardiovascular disease, and 811 who died from other cause. Compared to participants who were NHW, NHB adults with cancer had a significantly higher overall mortality rate (HR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.34–1.89) and cancer-specific mortality (HR, 2.03; 95% CI, 1.60–2.59; Fig. 1). Cancer survivors with each unfavorable SDoH variable, except access to regular health care, was significantly associated with higher all-cause, cancer-specific, and non-cancer mortality in the multivariable model adjusted for age (MV model 1), and adjusted for age, gender, race and ethnicity (MV model 2; Table 2). After adjustment for age, gender, race and ethnicity and other SDoHs, including unemployment status (HR, 1.83; 95% CI, 1.58–2.12; P < 0.001), family income-to-poverty less than 2.4 (HR, 1.51; 95% CI, 1.32–1.72; P < 0.001), education less than high school attached (HR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.05–1.44; P = 0.012), government or none of health insurance (HR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.05–1.36; P = 0.007), renting a home or other housing arrangement environment (HR, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.20–1.62; P < 0.001), and not being married nor living with a partner (HR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.08–1.38; P < 0.001) were significantly associated with an increased risk for all-cause mortality, which was similar to non-cancer mortality (Table 2). Furthermore, unemployed individuals (HR, 2.13; 95% CI, 1.62–2.79; P < 0.001), family income-to-poverty less than 2.4 (HR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.09–1.66; P = 0.006), and not being married nor living with a partner (HR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.08–1.38; P < 0.001) were significantly associated with an increased cancer-specific mortality risk compared to those with favorable SDoH (Table 2). Specifically, individuals of being unemployed status were associated with almost more than 1.9- and 2.2-fold higher all-cause mortality and cancer-specific mortality rates, respectively.

Fig. 1

All-cause mortality (A), cancer-specific mortality (B), and hazard ratios in US adults diagnosed with cancers aged 20 years or older by race and ethnicity. Note: Kaplan–Meier curves showed cumulative mortality probability race and ethnicity using age as the timescale. The number at risk was unweighted observed frequencies. Cumulative mortality rates were estimated with the use of survey weights. The bar chart showed HRs of all-cause and cancer-specific mortality associated with race and ethnicity, adjusted for age, and gender. Error bars were 95% CIs. NHW indicated non-Hispanic White; NHB indicated non-Hispanic Black; HR indicated hazard ratio; ns was the abbreviation of no significance; *** meant p < 0.001, ** meant p < 0.01, and * meant p < 0.05

Table 2 Association of SDoH With All-Cause and Cancer Mortality Among US Cancer Survivors Age 20 Years or Older, NHANES, 1999 to 2018

Cancer survivors with a greater cumulative number of SDoHs were significantly associated with an increased risk of death from all-cause and cancer (Additional file 1: Fig. S4; P < 0.001). In the multivariable of MV model 1 (adjusted for age, gender, race, and ethnic), the HRs for all-cause and cancer-specific mortality were 1.54 (95% CI, 1.25–1.89) and 1.52 (95% CI, 1.04–2.22) for cancer survivors with 1 unfavorable SDoH, 1.81 (95% CI, 1.46–2.24) and 1.70 (95% CI, 1.20–2.24) for those with 2 unfavorable SDoHs, 2.42 (95% CI, 1.97–2.97) and 2.22 (95% CI, 1.51–3.26) for those with 3 unfavorable SDoHs, 3.22 (95% CI, 2.48–4.19) and 2.44 (95% CI, 1.60–3.72) for those with 4 unfavorable SDoHs, 3.99 (95% CI, 2.99–5.33) and 3.60 (95% CI, 2.25–5.75) for those with 5 unfavorable SDoHs, and 6.34 (95% CI, 4.51–8.90) and 5.00 (95% CI, 3.00–8.31) for those with 6 or more unfavorable SDoHs, respectively, compared with of whom without unfavorable SDoH (Fig. 2). Kaplan–Meier curves were used to estimate the cumulative probability of all-cause and cancer-specific mortality using age as the timescale. The all-cause and cancer-specific mortality rates were significant across the several groups with a cumulative number of unfavorable SDoHs (Fig. 2, P < 0.001). Pairwise comparison using log-rank showed that the all-cause mortality rate was similar and not significantly different among cancer survivors with 0, 1, 2, and 3 cumulative number of unfavorable SDoH across the entire age cohort (Additional file 1: Table S4). There was no significant difference in cancer-specific mortality among cancer survivors with 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 cumulative number of unfavorable SDoH (Additional file 1: Table S5). Based on the linear dose–response analysis fitted curves (unfavorable SDoH ranged from 0 to 8), every cumulative unfavorable SDoH increase was significantly associated with 64% increased risks of death from all-cause (HR per 1-number increase, 1.64 [95% CI, 1.50–1.78]), and 53% of cancer (HR per 1-number increase, 1.53 [95% CI, 1.45–1.60]) (Additional file 1: Fig. S5 and Table 2; P < 0.001 for linear trend).

Fig. 2

All-cause mortality (A), cancer-specific mortality (B), and hazard ratios in US adults diagnosed with cancer aged 20 years or older according to the cumulative number of unfavorable SDoH. Note: Kaplan–Meier curves showed cumulative mortality probability by age and a cumulative number of unfavorable SDoH using age as the timescale. The number at risk is unweighted observed frequencies. Cumulative mortality rates were estimated with the use of survey weights. Bar chart showed hazard ratios of all-cause mortality and cancer-specific mortality associated with a number of unfavorable SDoH, adjusted for age, gender, and race and ethnicity; error bars were 95% CIs. A Compared to those with 0 unfavorable SDoH, all-cause mortality of hazard ratios (95% CI) for cancer survivors with 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, or ≥ 6 unfavorable SDoH were 1.54 (1.25–1.89), 1.81 (1.46–2.24), 2.42 (1.97–2.97), 3.22 (2.48–4.19), 3.99 (2.99–5.33), and 6.34 (4.51–8.90), respectively. B Compared to those with 0 unfavorable SDoH, cancer-specific mortality of hazard ratios (95% CI) for cancer survivors with 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, or ≥ 6 unfavorable SDoH were 1.52 (1.04–2.22), 1.70 (1.20–2.24), 2.22 (1.51–3.26), 2.44 (1.60–3.72), 3.60 (2.25–5.75), and 5.00 (3.00–8.31), respectively. ns was the abbreviation of no significance; *** meant p < 0.001, ** meant p < 0.01, and * meant p < 0.05

Age-adjusted/ age-gender-adjusted all-cause mortality and cancer-specific mortality risk were significantly higher in NHB cancer survivors when compared with NHW. Further adjustment for all SDoH factors, black-white disparity in cancer-specific mortality was still observed (HR 1.45, 95% CI 1.07–1.96), and the all-cause mortality did not show a statistically significant difference (HR, 1.08; 95% CI 0.89–1.30; Table 3). In the mediation analysis, the socioeconomic factor of unemployment (17.5% for all-cause mortality; 15.3% for cancer-specific mortality) can mostly explain the racial disparity in all-cause and cancer-specific mortality, and unemployment was associated with a nearly 90% and 120% greater all-cause and cancer-specific mortality, respectively. A family income-to-poverty ratio less than 2.4 (15.7%), an education less than high school (8.1%), government health insurance (6.9%), renting a home or other housing arrangement (15.4%), and not being married nor living with a partner (13.4%) indicated effective relative contribution to the disparity of all-cause mortality between NHB and NHW cancer survivors. An additional factor (not being married nor living with a partner [10.2%]) contributed significantly to the racial difference in cancer-specific mortality (Table 3).

Table 3 Mediation analysis by SDoH of the difference between NHB and NHW racial groups in all-cause death among US cancer survivors aged 20 or older

In the subgroup analysis, NHW cancer survivors who were unemployed, a lower level of PIR, an education less than high school, government or none of health insurance, renting a home or other housing arrangement, and not being married nor living with a partner were significantly more likely to die of all-cause mortality compared to NHW cancer survivors without unfavorable SDoH. Unemployment and not being married nor living with a partner were significantly associated with a higher risk of cancer-specific mortality (Additional file 1: Table S6). Being unemployed and having no access to a regular health care facility or emergency room was significantly associated with all-cause mortality in NHB cancer survivors. Only unemployed status was associated with cancer-specific mortality (Additional file 1: Table S6). In the stratified analysis by gender (female and male), almost all unfavorable SDoH were significantly associated with greater all-cause and cancer-specific mortality for female and male subgroups after adjusting for age, except for cancer-specific mortality for unfavorable home ownership (Additional file 1: Table S7). In all sensitivity analyses excluding mortalities that happened during the first 2-year follow-up since the baseline interview, all results remained similar in association with unfavorable SDoH with all-cause, cancer-specific, and non-cancer mortality (Additional file 1: Table S8).

In this US nationally representative cohort study of cancer survivors, we found that NHB and Hispanic adult cancer survivors self-reported a higher proportion of multiple unfavorable SDoHs compared to NHW adults diagnosed with cancer. Compared to NHW cancer survivors, NHB cancer survivors had significantly higher all-cause and cancer-specific mortality after adjusting for age and gender. In addition, after further adjusting for all SDoH, there was no longer a difference between NHB and NHW cancer survivors in all-cause mortality, but a significant difference in cancer-specific mortality was still observed. These findings suggest that racial differences in all-cause mortality between NHW and NHB cancer survivors were largely attributable to the explained by differences in SDoH, while cancer-specific mortality disparities were partly explained by differences in SDoH. Furthermore, unfavorable SDoH were associated with a higher risk of all-cause and cancer-specific mortality for cancer survivors. During the 20 years of follow-up, an increasing number of unfavorable SDoHs in the same individual was associated with an increased risk of dying from all causes, cancer, and noncancer causes, even after adjusting for demographic factors, such as age, gender, and race. Of note, there were significantly linear dose–response relationships between the cumulative number of unfavorable SDoHs and all-cause and cancer-specific mortality among cancer survivors, and cancer survivors having six or more unfavorable SDoH increased the HR for mortality of 6.34 and 5.00 compared to those having no unfavorable SDoH, respectively.

NHB cancer survivors were more likely than NHW patients to have unfavorable levels of all SDoH. Compared to NHW cancer survivors, NHB and Hispanic cancer survivors were 3.0 times and 3.9 times more likely to experience six or more unfavorable SDoHs, respectively, which may partly explain the racial disparity in mortality. Most predominantly, NHB cancer survivors were 1.6 times more likely than NHW cancer survivors to have family PIR less than 2.4, which was associated with almost 50% and 25% greater all-cause mortality and cancer-specific mortality, respectively. Most recently, Connolly et al. [30] conducted a study involving a cohort of 3590 participants from NHANES between 1999 and 2014, and demonstrated that the SDoH level was more favorable for NHW compared to NHB adolescents. Our finding was consistent with another previous study that reported a lower level of PIR, lower level of education attachment, lack of health insurance coverage, dietary insecurity, and limited health access were more common in NHB compared to NHW, which was a key mediator in explaining race disparity in all-cause and cause-specific mortality, especially cardiovascular disease and neoplasms [17, 40].

The persistent disparities in survival by race and ethnicity among cancer patients have been well-documented [2,3,4, 6, 41], and these disparities between NHB and NHW cancer survivors were particularly stark [42]. Indeed, the overall cancer mortality in 2022 for male and female together was 12% (166.8 vs. 149.3 per 100,000 persons, respectively) higher in NHB compared to NHW cancer survivors [6]. However, racial differences were not the only factor that contributed to observed mortality disparity and the underlying causes attributed to these disparities have not been well established [43]. Various factors have been suggested as contributors to these racial and ethnic disparities in survival outcomes among cancer survivors, including differences in tumor characteristics [44, 45], neighborhood socioeconomic deprivation [42], and accessibility to health care. In the current study, disparities in the all-cause mortality HR for NHB cancer survivors compared to NHW cancer survivors decreased from 1.59 (95% CI, 1.36–1.86) to 1.09 (95% CI, 0.91–1.31) after adjusting for all SDoHs, which mostly mediated the racial disparity in all-cause mortality. With respect to cancer-specific mortality, the HR for NHB cancer survivors compared to NHW cancer survivors decreased from 2.04 (95% CI, 1.60–2.62) to 1.45 (95% CI, 1.07–1.96) after adjusting for all SDoHs, which has a partly mediator role in the racial difference. We found that cancer survivors with employed, student or retired status (17.5% relative contribution), and PIR more than 2.4 (15.7% relative contribution) explained the greatest percentage of disparities in all-cause mortality. Furthermore, we also showed that employed, student, or retired status (15.3% relative contribution) and being married or living with a partner (10.2% relative contribution) explained the largest portions of disparities in cancer-specific mortality. Taken together, the traditional socioeconomic factors consisting of household income, level of education completed, and unemployment status were important explanatory factors, that mediated around 45% and 25% of all-cause and cancer-specific mortality in survival inequities between NHB and NHW cancer survivors, respectively, which was consistent with the findings of Bundy et al. (nearly 50% mediated the differential in all-cause premature mortality) [25]. The SDoH, through an impact on occupational opportunities and income levels, have a substantial influence on insurance coverage, which was one of the main factors determining access to and delivery of health care services in the US as well as associated disparities in survival [40]. Conversely, these traditional economic factors have a greater effect on the racial/ethnic disparities in the general population compared to cancer patients. Specifically, Luo et al. [20] suggested that income mediated 62% of the association in mortality between NHB and NHW, which was consistent with the dominant contributors to family income (40%) and education (19%) to the gap between NHB and NHW adult populations [17]. Interestingly, NHW cancer survivors were approximately 25% more likely to be married or living with a partner compared to NHB cancer survivors. Being married or living with a partner was associated with the cancer-related survival benefits, possibly due to increased social support and higher psychological well-being and instrumental support, helping navigate the health care system [46, 47]. According to Fuzzel et al. [48], barriers to health care accessibility and insurance coverage have a significant impact on rates of cancer screening, as well as the burden and attributions of the disease. These findings suggested SDoH factors, as an important mediator, drive racial health disparities, as well as all-cause and cancer-specific mortality, highlighting the necessity of the level of SDoH contexts for all people, especially those who are more vulnerable to unfavorable SDoH.

The cumulative adverse SDoHs were associated with poor all-cause survival and cause-specific survival rates among the cancer-free population have been previously reported, e.g., among patients with cardiovascular disease. Sameroff et al. [49] reported that cumulative unfavorable social risk factors, such as food insecurity combined with social isolation and loneliness, have a higher relevance to poor health outcomes than single social risk factors. Jilani et al. [50] suggested that greater SDoH adversity was linked to a higher burden of cardiovascular risk factors and poor health outcomes, such as stroke, myocardial infarction, coronary heart disease, heart failure, and mortality. Similarly, Zhang et al. [16] combined family income level, occupation, education level, and health insurance to measure socioeconomic status, and reported that participants who met low socioeconomic status had higher risks of all-cause mortality (HR, 2.13 and 95% CI, 1.90–2.38 in the US NHANES; HR, 1.96 and 95% CI, 1.87–2.06 in the UK Biobank), cardiovascular disease mortality (HR, 2.25; 95% CI, 2.00–2.53), and incident cardiovascular disease (HR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.52–1.79) in UK Biobank, compared to high socioeconomic status. Our results were consistent with the findings of a study in which each additional SDoH conferred additional cancer-related mortality, compared to cancer survivors without any SDoH (1 SDoH [HR, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.11–1.75], 2 SDoHs [HR, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.26–2.07], and ≥ 3 SDoHs [HR, 2.09; 95% CI, 1.58–2.75]) [13]. In contrast, Weires et al. [51] observed that women with a higher socioeconomic status showed increased mortality due to breast cancer in Sweden. This finding may be due to the structure of the Swedish family cancer database (Swedes born after 1931 and their biological parents), as well as analytical restrictions on individuals 30–60 years of age in 1960, which may exclude low-socioeconomic adults with severe health problems. Previous studies have shown that these unfavorable SDoH have a tendency to cluster in individuals [13, 23]. For example, individuals in the general US population who self-reported food insecurity were more likely to be combined with a low level of education attachment, not being married, a low level of family income, and a bad lifestyle. This finding was consistent with our observation that these unfavorable SDoH were not isolated but interrelated, and each unfavorable SDoH included in our study has been found to independently increase the risk of mortality. Compared to most previous studies based on a single SDoH, we found that there was a simple linear dose–response relationship reflecting the cumulative effect of multiple unfavorable SDoHs on all-cause and cancer-specific mortality. Collectively, these SDoH appear to synergistically increase the risk of all-cause and cancer-specific mortality among cancer survivors. However, the cumulative risk derived from a sum of the number of unfavorable SDoH assumed that all SDoH had equal and independent effects on survival outcomes, which might not be precise. We suggest that future research may need to use more complex models, such as interaction models, to more accurately capture the complex interactions of unfavorable SDoH.

Strengths and limitations

The major strength of this study was the use of large sample size data from the NHANES, which provides an opportunity to comprehensively evaluate the complex relations of SDoH with all-cause and cancer-specific mortality among cancer survivors. In addition, we focused on multiple SDoH factors and estimated the effect of accumulating unfavorable SDoH burden on mortality. We also performed mediation analysis to show the contribution of SDoH to disparities in all-cause and cancer-specific mortality. There were some limitations in the present study. First, we conducted the analyses based on the follow-up of time-to-event, however, all data on SDoH variables were only assessed at the baseline interview, which may not reflect factors that changed during the follow-up period. Therefore, our study was not able to quantify the effect of changes in eight SDoH on the mortality of cancer survivors over time. It is essential to conduct several repeated interviews about the level of SDoH during the follow-up period to reveal the influence of SDoH factors on survival among cancer survivors. Second, the assessment of SDoH was limited by the availability of variables in the NHANES database. Some SDoH such as neighborhood environment, social support, and exposure to racism, were not widely available, which may also contribute to the all-cause and cancer-specific mortality. Third, the follow-up duration was relatively short (median, 81 months) and an important bias among these cancer survivors such that socially disadvantaged who died during the study period might have had severe disease at baseline.