Now that the election is over, you may be feeling tired, discouraged, and disillusioned, whether your preferred candidate won or not. you are not alone.

Survey after survey has found that Americans agree that the political system is not serving them.

Americans say they are angry at dysfunctional politics, disgusted by divisive rhetoric, fed up with a lack of options, and feel unheard and unrepresented. I am a mathematician who studies quantitative aspects of democracy, and in my view the reasons for this widespread dissatisfaction are clear. That’s because the mechanisms of American democracy are broken at a fundamental level.

Research shows that there are clear mathematical fixes for these dysfunctions that result in healthy democratic practices supported by evidence. It cannot solve all the ills of American democracy. For example, changing a Supreme Court decision or expanding voting access is more political or administrative than based on mathematics. Nevertheless, each of these changes, especially in combination with each other, has the potential to make American democracy more responsive to its citizens.

Problem: Multiple voting

Plurality voting, or winner-take-all, is how all but a handful of the 520,000 elected representatives in the United States are elected. It’s also mathematically the worst because it could give a victory to a candidate who doesn’t have majority support. This method is fraught with mathematical problems such as vote splitting and spoiler effects, both of which result in victories for less popular candidates.

Solution: ranked voting

Ranked choice voting allows voters to sort their preferences rather than simply registering their top choices.

The system, used around the world including Australia and New Zealand, and in more than 50 jurisdictions in the United States, including Alaska, New York City and Minneapolis, selects candidates with broad support. Voters don’t have to worry about wasting their votes, so they can use this method to show support for a third-party candidate even if they don’t win. This method also punishes negative campaigning, as a candidate can win not only as the first choice but also as some voters’ second or third choice.

Andriy Yalansky/iStock/Getty Images Plus

Issue: Electoral College

The electoral system is a unique and archaic system that no country in the world wants to get involved with. The legacy of slavery and the Constitution’s framers’ skepticism that the people were wise enough to make good decisions for themselves gave voters in some states more power than others in choosing the president. It is only made worse by the many mathematical problems it presents.

Solution: Popularity Vote

Evidence shows that switching to popular voting eliminates these biases. But history shows that even if 63% of Americans support abolishing the electoral college, the necessary constitutional changes are unlikely to materialize.

One possible way to avoid the need for a constitutional amendment is the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, which is currently supported by 17 states, including California, Illinois, and Washington, D.C. Electors from each state included in the agreement would need to vote for the winner. A nationwide popularity vote. However, it will not take effect until enough states participate to reach 270 electoral votes, the threshold for victory. Currently, 209 states with a total of 209 electoral votes support the measure.

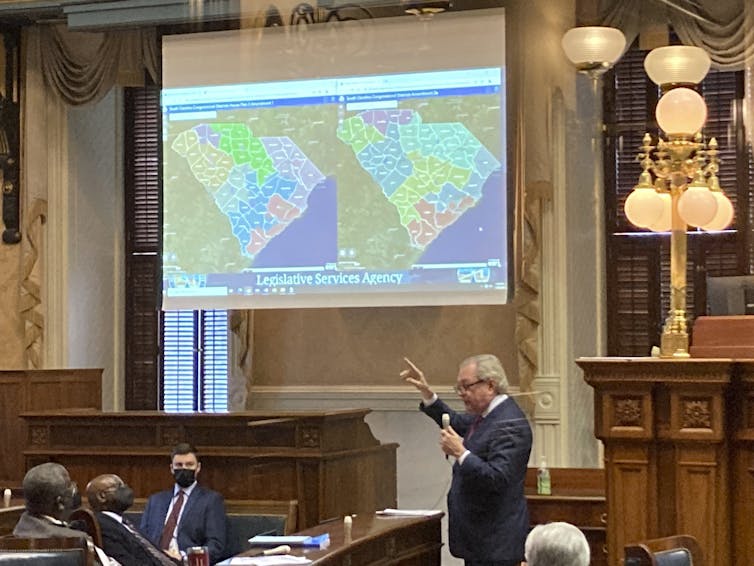

Problem: Solo Winner District

Because of winner-take-all voting, Congressional and state officials do not necessarily reflect the partisan makeup of their districts, giving one party disproportionate representation.

Solution: Districts with multiple winners

Most democracies around the world have geographically large electoral districts and elect multiple candidates at the same time. Multi-win districts are designed to provide proportional representation. Currently, all nine Massachusetts members of the U.S. House of Representatives are Democrats, even though one-third of Massachusetts voters typically choose Republican candidates. But if Massachusetts had three Congressional districts instead of nine, each electing three House members, one-third of the seats would go to Republicans, depending on the state’s percentage of Republican voters. It turns out. Districts with multiple winners also effectively eliminate gerrymandering.

Jeffrey Collins/Associated Press

Issue: Party primaries

Approximately 10% of eligible voters voted in the Congressional primary. These voters often represent a passionate constituency that can boost fringe or extreme candidates running in less competitive popular elections due to a combination of factors such as plurality voting and single-winner districts. .

Although the final numbers for 2024 are not yet in, this one-tenth of voters effectively decided 83% of parliamentary seats in 2020. Lawmakers shape politics to suit the demands of their constituents and can hold office for decades with little effort. .

Presidential primaries have their own mathematical flaws that distort voter preferences and reward polarizing candidates who can garner support.

Solution: Hold a primary or not hold one at all.

California, Colorado, and Nevada have open, nonpartisan primary voting systems. The top three or four candidates advance to the general election, followed by ranked-choice voting. This structure increases voter participation and produces more representative results.

A simpler solution might be to eliminate primaries and hold just one public general election with ranked-choice voting.

Vintage Halloween Collector via Flickr, CC BY-ND

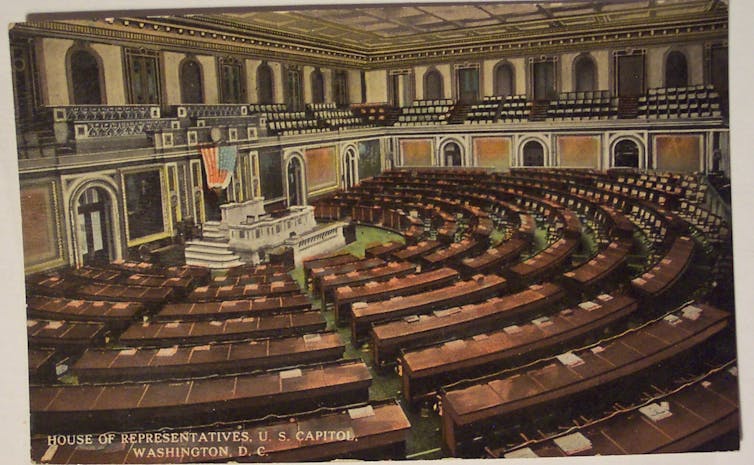

Issue: Size of the House of Representatives

The first amendment proposed by the framers of the Constitution was one that would have required the size of the House of Representatives to expand as the country’s population grew. For close contact between officials and voters, a ratio of 30,000 to 50,000 people per House member was preferred. Their amendment was never approved.

The current ratio is 760,000 people per delegate. The size of the House of Commons is determined by law and has been fixed at 435 members since 1913. It’s hard to imagine a representative being able to speak knowledgeably about so many constituents or understand their collective needs and preferences.

Solution: Increase size

To reduce this ratio, the House of Representatives needs to be enlarged. The country’s population is over 337 million people, and James Madison’s wishes would require more than 6,700 members of Congress. That’s tricky. Most democracies seem to have either deliberately followed or naturally settled on a different formula in which the size of the parliament is approximately equal to the cube root of the country’s population.

In the United States, that number is currently close to 700, giving a population-to-representation ratio of 475,000 to 1. This would still upset Mr. Madison, but it’s far more representative than the status quo.

Would the Capitol be able to handle such an expansion? Architectural research shows that this is not a problem.