Unlock Editor’s Digest for free

FT editor Roula Khalaf has chosen her favorite stories in this weekly newsletter.

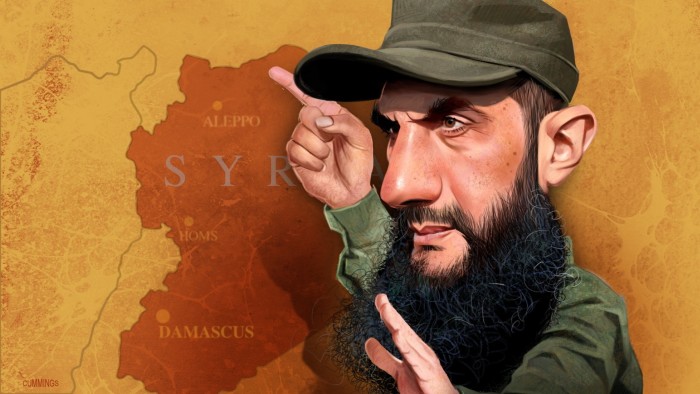

Dressed head to toe in khaki and surrounded by unarmed guards, Abu Mohammad al-Jolani strode triumphantly down the steps of Aleppo’s medieval citadel this week. The leader of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) was swarmed by supporters waving flags synonymous with the rebel group that had just captured Syria’s second-largest city in a blitzkrieg.

Jolani waved to stunned Aleppo residents before returning to the front line in a white jeep. He barely managed to smile. It was a politically astute move typical of an ambitious 42-year-old Islamist who has spent the past few years in the throes of political change. Jolani believes he will become Syria’s future leader if his forces succeed in overthrowing President Bashar al-Assad’s regime.

“Jolani is very smart about how to pick his moments and capitalize on them,” says Aaron Zelin, an expert on jihadism, Jolani and HTS. “He chose a symbolic location. There were no guns around. It was designed to make him look like a serious political leader.”

The appearance was the culmination of a week-long offensive by HTS-led rebels and one of the most shocking moments in the bloody 13-year civil war, which has seen the front line frozen in an uneasy stalemate. It was a stunning reversal in the conflict.

Days after capturing Aleppo, the rebels captured another major city, Hama, and soon moved south toward Homs. The capital Damascus, which Jolani has long had in mind, could be his next choice.

The successful attack highlighted the fragility of President Assad’s grip on his fractured homeland. His forces, although supported by a network of Russian, Iranian and Tehran proxies, appeared to disappear as the rebels advanced.

It was also the result of years of careful preparation by Jolani, who helped the group recover from the brink of collapse five years ago. He moderated Islamic doctrine, strengthened the military, and established a civilian-led government.

That change was evident during the attack. Jolani used recent operations against tribes, former adversaries, and minority groups to broker surrenders and order protection for minorities. He also issued a statement against Russia, which has supported Assad for many years, suggesting that HTS and Russia could find common ground in rebuilding Syria.

Born Ahmed Hussein al-Sharah in 1982, Jolani spent his first seven years in Saudi Arabia, where his father worked as a petroleum engineer. He then moved to Damascus, the city where his grandfather had arrived after Israel’s occupation of Syria’s Golan Heights.

Jolani said he became radicalized during the second intifada in 2000. “I was 17 or 18 years old at the time, and I started thinking about how I could fulfill my duty to protect people oppressed by occupiers and invaders,” he says. he told PBS Frontline in one of his only interviews with Western media so far in 2021.

Painted to resist the 2003 US invasion of Iraq, he arrived in Baghdad on a long bus ride from Damascus just weeks before US troops invaded. He spent the next few years rising through the ranks of the rebel army before being captured and imprisoned at Camp Bucca prison, now notorious for nurturing generations of jihadi leaders. It is known for.

Jolani, who was released at the start of the Syrian uprising in 2011, crossed the border with a bag full of cash and al-Qaeda expansion missions. Many in Iraq were happy to see him go. There he was in conflict with al-Qaeda leaders, and the conflict continued to grow. Jolani distanced himself from transnational jihadist ideology and expanded his rebel forces under the auspices of the nationalist struggle for Syria. Eventually he broke away and openly fought al-Qaeda and ISIS.

He also eliminated the more radical elements of the HTS and helped build a technocratic government. “Jolani’s fate is being written right now. How he manages his next steps, and if HTS manages to remain inclusive, will determine what his legacy will be,” the think tank said. , says Crisis Group jihad expert Jerome Drevon.

Jolani stands out among her colleagues. He is well-educated, urbane, and soft-spoken. Drevon says his middle-class background “helped shape his approach to Islam.” “He often said that the real world must guide your Islam, that you cannot impose your Islam on the real world.”

But Zelin, an expert on jihadism, warns that this does not make Jolani a liberal democrat, describing him as a “charismatic leader of a dictatorship.”

This became the key to his success. So do his fellow young advisors. “These are very educated people who understand the outside world. They don’t have a banker mentality,” said Dareen, Drevon’s colleague at Crisis Group, who has met with Jolani numerous times since 2019.・Khalifa says:

The question is how far the transformation will go. The US has designated HTS a terrorist organization and placed a $10 million bounty on Jolani’s head, a move that could complicate his ambitions to build ties with the West and lead Syria. There is.

This week, Jolani told Khalifa that he would consider disbanding the group and that Aleppo would be managed by an interim body that would respect the city’s social structure and diversity. It remains to be seen whether the group will be able to reconcile this plan with its jihadist roots.

raya.jalabi@ft.com