CNN

—

On October 4, 1883, the legendary Orient Express left Paris Gare de l’Est for the first time and slowly wound its way through Europe to Constantinople, then known as Istanbul. During the seven-day round-trip, the 40 passengers, including several prominent writers and dignitaries, lived in the comfort of mahogany panels and spent time in smoking rooms and soft Spanish leather armchairs. .

But the most luxurious experience of all can be found in the dining car.

The menu, which ranged from oysters to chicken chasseur to turbot with green sauce, was so sumptuous that part of the luggage car had to be repurposed to make room for an additional icebox for food and alcohol. There was. Served by impeccably dressed waiters, guests drank from crystal goblets and ate on fine porcelain with silver cutlery. The interior of the restaurant was decorated with silk curtains and the spaces between the windows were decorated with artwork.

Newspaper correspondent Henri Opper de Blowitz, one of the passengers on the maiden voyage, wrote: Silver capsules in water decanters and champagne bottles blind the public eye both indoors and outdoors. ”

The luxurious passenger experience of the Orient Express was later immortalized in popular culture by writers such as Graham Greene and Agatha Christie. But eating on the go was truly a triumph of logistics and engineering. Just 40 years ago, the idea of preparing and serving hot meals on trains would have been almost unthinkable.

In the early days of rail travel, passengers either brought their own food or, if scheduled stops were allowed, ate at the station cafe. In Britain, for example, meals had been served in so-called railway refreshment rooms since the 1840s, but their quality was often questionable. Charles Dickens, a frequent user of British railways, told of his visit to one such facility. There, he recalls, he bought a pork pie consisting of “a sticky mass of gristle and grease, plundered from an iron-bound quarry with gold coins.” It’s like cultivating inhospitable soil. ”

Britain may have pioneered railway engineering in the 19th century, but the history of dining cars begins in America.

In 1865, engineer and businessman George Pullman ushered in a new era of comfort with the Pullman sleeping car, or “palace car,” and two years later launched a “hotel on wheels” called the President. The latter was the first railroad car to offer on-board meals prepared in a 3-foot by 6-foot kitchen, including regional specialties such as gumbo.

Following the highly successful President, Pullman launched its first-ever dedicated dining vehicle, the Delmonico. Delmonico’s is named after a New York restaurant considered America’s first fine dining restaurant. By the 1870s, dining cars could be found on sleeper trains across North America.

However, it was Georges Nagelmachers, a Belgian civil engineer and businessman, who brought this idea to Europe and took the experience to new heights.

He saw the potential of luxury sleeping cars in Europe and set out to transform rail travel on the continent with the International Wagon Ritz Company (CIWL, or simply Wagon Ritz), founded in 1872.

The company soon began producing some of the world’s most desirable dining and saloon cars. It is used not only on the famous Orient Express, but also on the Nord Express (from Paris to St. Petersburg), the Southern Express (from Paris to Lisbon), and dozens of other services. The company came to dominate luxury rail travel in mainland Europe by the early 20th century. Although Wagon’s Ritz also operated grand hotels along the line, onboard dining remained central to the romantic appeal of rail travel.

Meals were served at set times and supervised by the hotel manager. And according to Arthur Mettetal, who recently curated an exhibition on the history of the Wagon Ritz dining car at France’s Les Rencontres d’Arles photography festival, from the table service to the decorations, the vehicle is an art form of French living. It is said to embody this.

“Even though the menu was different, it was the same as what you would get at a really nice Parisian restaurant,” he told CNN on a video call. “Also, the combination of crockery, silverware, ornaments, and everything else was considered luxury at the time.”

The 1920s are considered the “Golden Age” of rail travel in the West. As Europe emerged from the ravages of World War I, business travelers and adventurous vacationers began to take advantage of the smoother, quieter, and faster steam locomotives.

When the Wagon Ritz line reached North Africa and the Middle East, modern metal cars replaced the old wooden ones. Meanwhile, notable artists and designers were commissioned to decorate the vehicles, including the palatial dining carriage.

By the end of the next decade, the company was operating more than 700 dining cars, but by then the even greater in-car luxury of in-seat dining was emerging.

A new fleet of Ritz wagons known as the Pullman Lounge (by this point the American industrialist’s name had become synonymous with luxury train travel) were introduced into various daytime services. Passengers did not have to wait until lunch or dinner time and were served their food directly on giant winged chairs with comfortable headrests. Mettetal said the vehicles had proven to be “innovative” and were “the most luxurious vehicles ever created.”

Wagon Ritz commissioned decorator René Proulx and glazier René Lalique to design a new Pullman carriage for the Orient Express. They feature elegant marquetry and molded glass panels, and even the luggage shelves have been “transformed into Art Deco jewels,” Mettetal’s exhibition notes say.

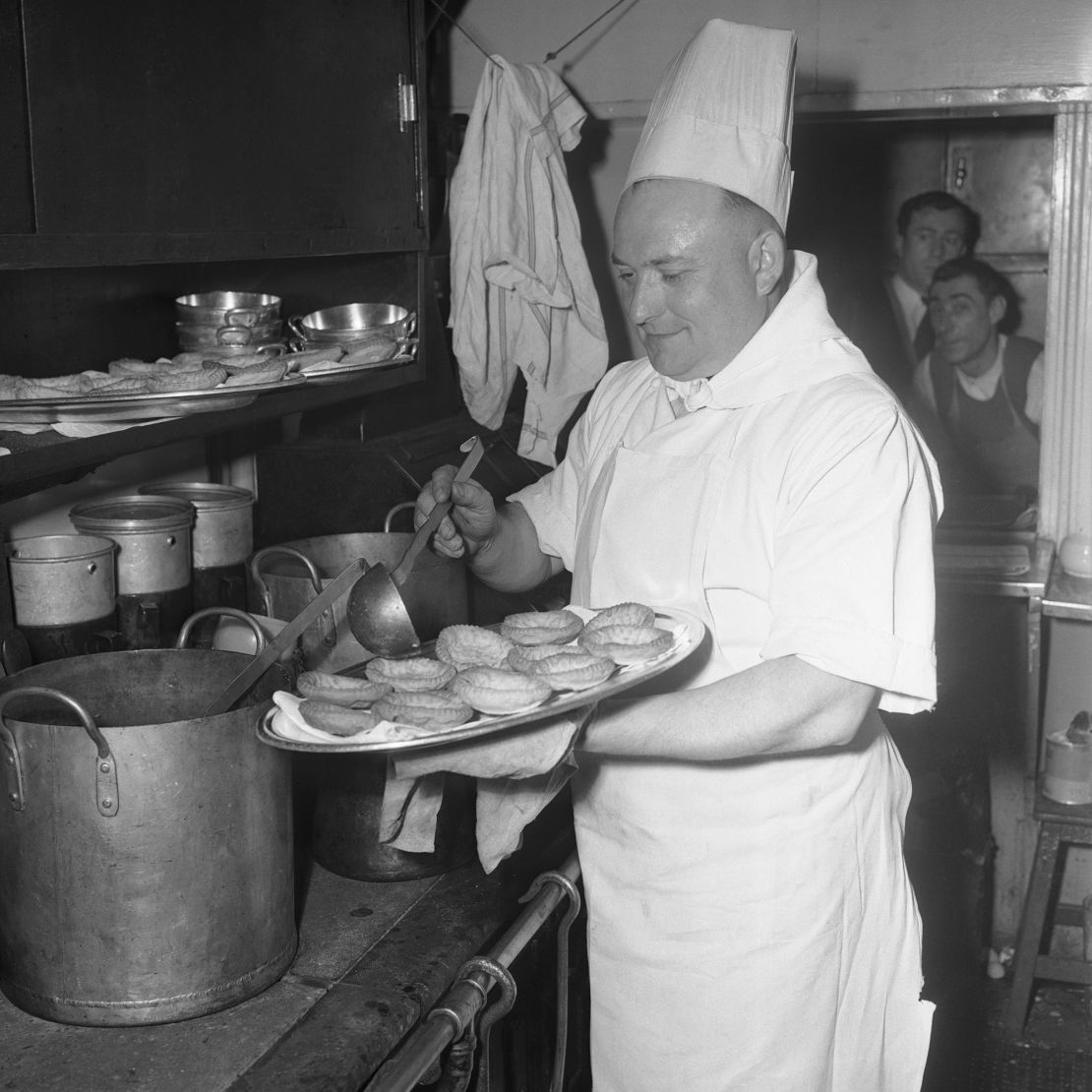

The ease and convenience of dining at Wagons-Lits belied the complex logistics operations. Starting in 1919, the company operated a central kitchen in a hotel in Paris, preparing (and in some cases pre-cooking) food destined for the railway lines, offloading the chefs onboard the trains.

“The kitchen in the dining car was only 7 to 8 square meters (75 to 86 square feet), so preparing meals for more than 100 people was a real challenge,” Mettetal said.

With the help of this off-site kitchen, Wagon’s Ritz was serving approximately 2.5 million meals a year by 1947. But this decentralized production model also contained the seeds of the dining car’s eventual demise.

After World War II, the way railways and passenger services were operated changed significantly. Trains became faster and travelers had less leisure time to kill while traveling. With the rise of commercial air travel in the 1950s and the explosion of private car ownership across Europe, trains were no longer considered the most luxurious means of travel.

The economics of food production also evolved along the model pioneered by airlines. In this model, meals were prepared entirely off-site and ultimately eaten from compartmentalized plastic platters with disposable cutlery and napkins. In 1956, Wagons-Lits opened a new modern commercial kitchen with extensive refrigeration systems and meat storage, where a staff of over 250 people prepared meals for every train leaving Paris. .

Food has slipped down travelers’ priority lists. Meanwhile, Wagon Ritz service has become more about convenience than comfort, including self-service buffet vehicles packed with cheaper cafeteria-style food. In the 1960s, the company introduced the portable “Mini Bar,” which initially sold 23 products, including sandwiches. The minibar moved throughout the train and served food at eye level to seated passengers.

When it comes to food, Mettetal says, train operators have started touting the idea of modernity and innovation rather than luxury. Mr. Mettetal’s exhibition (and accompanying book) features advertising photographs from the archives of the now-defunct Wagon Ritz and the French National Railways. SNCF. A 1966 promotional image (pictured above) shows the dining area of Le Capitole, a freight car and Ritz express train between Paris and Toulouse, clearly showing the train’s speedometer.

“It’s an image that promotes (the idea) that you can eat on a train traveling at more than 200 kilometers per hour,” Mettetal said. “But this movie is completely different because it’s just a couple and a family with one child. Sociologically speaking, this is a new type of passenger.”

By the 1970s and 1980s, kitchens had all but disappeared from European railways. And despite a resurgence of interest in rail travel on the continent, dining cars (or even cars with kitchens) now serve primarily as tourist services. Many are tapping into nostalgia, with meals being served on trains, like the new Orient Express, which will return in 2025 with a dining car that, according to its website, “reinterprets the codes of legendary trains.” It provides an opportunity to revisit the old days. Not just luxury, but luxury.