Getty Images

Getty Images“Think of it as a cricket cake with fish paste,” the chef told a man in the buffet line, encouraging him to try a steaming bowl of spicy laksa, a coconut noodle soup packed with cricket protein.

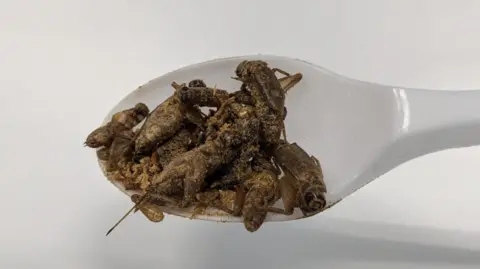

Next to it was a plate of chilli crickets – stir-fried mud crabs bathed in a rich, sweet chilli sauce, a bug version of a popular Singaporean dish.

It looked just like any other buffet, except every dish had crickets as a main ingredient.

Among the queue was a woman gently placing dishes of stir-fried Korean glass noodles topped with finely chopped crickets onto plates, and a man patiently sear a young chef.

You’d expect attendees to devour their feasts in no time at all – after all, they were among more than 600 scientists, entrepreneurs and environmentalists from around the world who had descended on Singapore as part of a mission to make insects tasty. The name of the conference said it all: “Feed the World with Insects.”

Still, many more were drawn to the buffet next to the insect dishes, which some might argue were common fare: wild barramundi with lemongrass and lime, grilled sirloin steak with onion marmalade, and coconut vegetable curry.

According to the United Nations, around two billion people – roughly a quarter of the world’s population – already eat insects as part of their daily diet.

A growing number of insect enthusiasts champion insects as a healthy, environmentally friendly option, and say more people should join in. But is the prospect of saving the planet enough to persuade people to eat the best bugs around?

Insect-like

“The focus has to be on making it taste good,” said New York-based chef Joseph Yun, who, along with Singaporean chef Nicholas Loh, created a cricket-based menu for the conference and had permission to use only crickets at the event.

“The idea that insects are sustainable, nutritious and can address food security doesn’t go far enough to make them tasty, let alone appetizing,” he added.

Research has shown that crickets are rich in protein, and raising them requires less water and land than farming livestock.

Some countries are encouraging, if not supporting, eating insects: Singapore recently approved 16 insect species for consumption, including crickets, silkworms, grasshoppers and honeybees.

The edible insect industry is still in its infancy and is regulated in only a few countries, including the European Union, Australia, New Zealand, South Korea and Thailand. Estimates range from $400 million to $1.4 billion (£303 million to £1.06 billion).

Insects will feed the world

Insects will feed the worldChefs like Nicholas Law have had to come on board and find ways to “deconstruct” insects and use them in cooking, because people aren’t necessarily keen on eating them in their “natural form.”

For the conference, Mr Low revamped the popular laksa, using a pate made from minced crickets instead of the usual fish paste.

It was also tricky to mask the earthy smell of the bugs, and a “strong-flavoured” dish like laksa was ideal, as the savoury flavour of the original recipe would distract people from the smell of the squashed bugs.

Low said crickets offered little room for experimentation — typically fried or ground into a fine powder for a satisfying crunch — unlike meat, which is versatile in dishes from braises to barbecues.

He can’t imagine cooking crickets every day: “I’m more likely to cook them as a special dish on a larger menu.”

Since Singapore approved cooking with insects, several restaurants have been experimenting with them: Seafood restaurants are sprinkling crickets into satay and squid ink pasta, and serving them as a garnish to fish head curry.

Of course, some are more enthusiastic about the challenge: Tokyo-based Takeo Cafe has been serving insect dishes to diners for the past decade.

Menu items include a salad of twin Madagascar cockroaches nestled on leaves and cherry tomatoes, a generous serving of ice cream topped with three tiny grasshoppers, and even a cocktail made with a spirit made from silkworm faeces.

BBC/Kelly Ng

BBC/Kelly Ng“The most important thing is (customer) curiosity,” says Takeo’s chief sustainability officer, Saeki Shinjiro.

What about the environment? “Customers don’t really care,” he says.

Just to be on the safe side, Takeo also offers a bug-free menu: “When designing the menu, we are careful not to discriminate against people who don’t eat bugs. Some customers simply come with friends,” Shinjiro said.

“We don’t want to make those people feel uncomfortable. There’s no need to force them to eat insects.”

Our Food and Us

But that wasn’t always the case: for centuries insects have been a valuable food source in many parts of the world.

In Japan, grasshoppers, silkworms and hornets have traditionally been eaten in inland areas where meat and fish are scarce, a practice that resurfaced during food shortages during World War II, says Takeo store manager Michiko Miura.

Today, crickets and silkworms are common snacks sold at night markets in Thailand, but customers in Mexico City are paying hundreds of dollars for ant larvae, considered a delicacy by the Aztecs, who ruled the region from the 14th to 16th centuries.

But insect experts fear these culinary traditions are eroding with globalisation, as people who eat insects now associate it with poverty.

New York-based chef Joseph Yoon said there was a “growing sense of shame” in places with a long history of eating insects, such as Asia, Africa and South America.

“They now have a glimpse into foreign cultures through the internet and feel embarrassed about eating insects because it’s not a custom elsewhere.”

Insects will feed the world

Insects will feed the worldIn her book Edible Insects and Human Evolution, anthropologist Julie Resnick argues that colonialism deepened prejudice against insect eating: She writes that Christopher Columbus and members of his expedition described Native American insect eating as “an act of bestiality worse than any beast on earth.”

Of course, people’s attitudes can change — after all, delicacies like sushi and lobster were once foreign concepts to most people.

Sushi was originally a working-class dish sold from street stalls, and lobster, known as the “poor man’s chicken,” was so plentiful it was once used to feed prisoners and slaves in the northeastern United States, says Keri Matiuk, a food researcher at Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University.

But as transportation networks developed, making travel easier, and food storage improved, more and more people were exposed to shellfish. As demand increased, so did the price and status of shellfish.

Dr Matwick said foods that were once considered “unusual” or even not food could slowly become more mainstream, “[but]cultural beliefs take time to change. It will take a while to change the perception that insects are disgusting and dirty.”

Some experts recommend raising children to be more tolerant of exotic foods, including insects, as future generations will bear the full impact of the climate crisis.

Insects may one day become as popular a “superfood” as quinoa or berries, eaten reluctantly rather than for the pleasure they bring with a buttery steak or a hearty bowl of ramen.

Singaporean chef Nicholas Loh doesn’t think there’s anything for now that will pressure people to change their eating habits, especially in wealthy places where almost anything you want is just a few clicks away.

Younger consumers may try it out of curiosity, but the novelty will wear off, he said.

“There are too many options, it’s hard to choose. I want to eat meat as meat and fish as fish.”