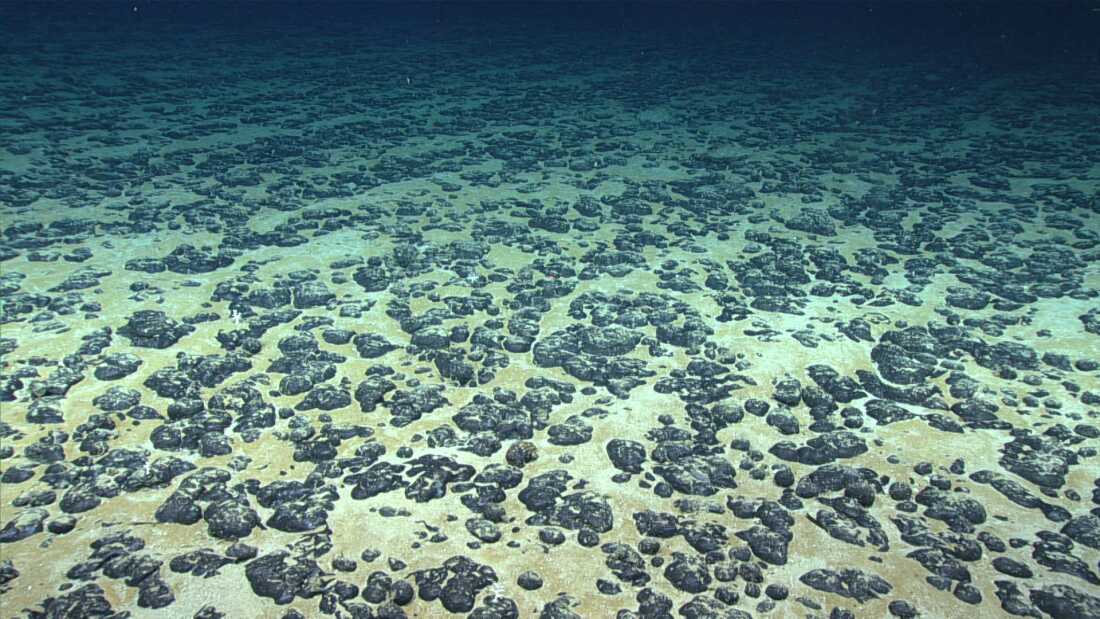

Negotiators are blaming rules for controlling mining on the seabed. There, important metals can be found in sediments called polymetal nodules. Here we see the nodule of ferromanganese in the North Atlantic. NOAA OCEAN EXPLORATION HIDE Caption

Toggle caption

NOAA Ocean Exploration

In the global competition for important minerals, one lesser known international organization holds the key to potential motherroads. This is a large amount of metal found on the remote seabed.

The International Seabed Authority (ISA) has worked for over a decade to create regulations for future deep sea mining. Negotiators say the process could take years to complete.

But now, one mining company plans to move forward if and if the rulebook is in place.

Metals Company, a startup based in Vancouver, British Columbia, claims it is ready to launch the world’s first deep-sea mine in the Eastern Pacific. This poses a challenge for ISA negotiators, which will be held this week in Kingston, Jamaica.

Experts say the results could have a major impact on marine ecosystems and restructure the mineral economy.

“We are deeply concerned that mining is not subject to regulations,” said Liz Karan, director of ocean governance at Pew Charitable Trusts. “It will have potentially disastrous consequences for marine health.”

Why mining the seabed?

Scientists know little about the deep seabed. Most of the seabeds are not mapped. Researchers believe that most species living there remain unidentified. But one thing is certain, there are a lot of metals out there, including the key materials used in technologies such as electric vehicle batteries.

US Geological Survey estimates that a single belt in the Eastern Pacific, known as the Clarion Clipperton Zone, contains more nickel, cobalt and manganese than all terrestrial reserves. These metals (plus copper) are bound to potato-shaped deposits called polymetal nodules, which are formed for millions of years so that seawater minerals contain minerals around bits of organic matter. These nodules are scattered across the sandy seabeds of the Clarion Clipperton Zone. This is about half the neighboring US region between Hawaii and Mexico.

These nodules have been tempted to become miners for decades. Mining companies claim that deep seabeds can provide a major new source of minerals independent of China, which controls the supply of many important minerals.

Vancouver-based startup Metals Company says it is ready to launch the world’s first deep-sea mine in the Eastern Pacific. Here, researcher Andrew K. Sweetman explains how a sample can be obtained in a 2021 study on the potential environmental impacts of mining. Carolyn Cole/Los Angeles Times hides captions via Getty Image

Toggle caption

Carolyn Cole/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

How does deep sea mining work?

To retrieve the nodule, the mining company plans to send private collector vehicles to the bottom of the ocean. School bus-sized metal companies vehicles craze along the seabed, covering the nodule, and passing through vertical tubes several miles long to the surface to the ship waiting for the surface. (Some observers describe this system as the world’s longest vacuum cleaner, but for important minerals instead of dust bunnies.)

In 2022, the metals company completed field testing of the system at the Clarion Clipperton Zone. The company is currently seeking permission to begin commercial production.

The metals company said it will apply for a mining and exploitation permit from the ISA on June 27, regardless of whether regulations have been finalized.

What are the environmental impacts?

No one knows for sure, as deep sea mining has never been done on a commercial scale.

Submarine mining supporters argue that it is less destructive than land mining.

Gerard Barron, CEO of Metals Company, points to Indonesia, one of the world’s leading nickel producers. In contrast, he insists that the vast, sandy plains of deep undersea ports live far less.

“For some reason, I think it’s okay for people to dig into the rainforest and put metal down, but are you debating whether to pick up these rocks sitting on the Abyssal plains?

Many marine scientists and policy makers disagree.

Researchers say they have identified more than 12 ways seabed mining can damage ocean ecosystems. Animals containing sponges and anemones grow on the nodule, so removing the nodule destroys its habitat. Sediment plumes released from mining operations can damage creatures adapted to the clear waters of the deep sea. Noise pollution caused by submarine mining can interfere with animal navigation and communication.

Multinomial nodules containing certain important minerals can be seen scattered across the seabeds of some of the ocean. Here, manganese nodules discovered in the southeastern United States in 2019. NOAA Office Office Office Office And Research Hidden Caption

Toggle caption

NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research

Hundreds of researchers are calling for a pause in deep sea mining until scientists learn more. Some companies, including automakers and high-tech companies such as BMW, Volkswagen, Volvo, Google and Samsung, have committed to not using undersea minerals.

Some mining companies say new technology could reduce damage. One startup, Impossible Metals, is developing a fleet of underwater robots floating above the seabed, rather than raw it along the seabed. The robot uses mechanical arms to pick visible, lifeless nodule. The company claims that the method eliminates sediment plumes and reduces noise pollution, but this technique has not been tested at the extreme depths where mining occurs.

Who decides whether mining has occurred?

Individual countries generally regulate mining within exclusive economic zones spanning 200 miles from the coast. A handful have begun allowing exploration of submarine minerals in Japan, the Cook Islands, Papua New Guinea and Norway (although Norway suspended the permitting process late last year).

But most of the seabed lies beneath the high seas, beyond the control of any nation. That’s where ISA has jurisdiction.

The ISA was launched in 1994 by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. This includes all major economies with coastlines except the United States, and the treaty was never ratified.

Polymetal nodules like these manganese nodules are formed for over millions of years, when minerals of seawater minerals are minerals around bits of organic matter. NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration Hide Caption

Toggle caption

NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration

The ISA allows 31 contracts that allow member states (and partners) to explore submarine minerals, primarily in the Clarion Clipperton Zone. China has snapped five of these exploration contracts. It’s more than any other country.

But no one has moved from exploration to exploitation. This is because the ISA has not finalized regulations regarding commercial scale extraction. ISA negotiators have spent more than a decade drafting a mining rulebook that covers everything from environmental rules to royalty payments.

ISA countries have set a goal of finalizing regulations this year. However, the key issues in the draft rulebook have not been resolved as negotiators meet this week to bring out details at ISA headquarters in Kingston, Jamaica. The ISA appears unlikely to complete this year’s regulations. Not to mention June 27th, when metal companies are planning to submit mining applications.

Around 30 ISA countries are seeking precautions for mining activities at least until the regulations are completed. Other countries have resisted these calls, including Nauru, Pacific Island Nation, which has partnered with metal companies on mining projects.

What could happen next?

The United Nations Sea Law Convention states that businesses can apply to mines before regulations are completed, but does not specify exactly how the ISA will evaluate such applications.

“This is unknown territory,” Curran said. “This is not something the ISA has a clear roadmap.”

The ISA can simply reject Metals Company applications out of hand. Or, perhaps if there are some strings attached, you can tentatively approve the application and reconsider the issue once regulations are finalized. Both approaches can cause legal disputes before international courts.

The third possibility is that metal companies have chosen to move forward outside the ISA’s legal framework. This is the possibility of inviting experts like Karan.

“I am deeply interested in the prospects of mining that are not happening in areas beyond national jurisdiction,” she said. “That would violate international law.”

“Nothing is off the table,” said Gerard Barron, CEO of Metals Company. He pointed out that the United States is not bound by ISA rules. Companies who want to begin extraction could theoretically do so by partnering with the US government that is not bound by the world’s undersea mining laws.

“The international community has the opportunity to implement these rules, but if they don’t, it doesn’t mean that the industry won’t move forward,” Baron said. “In some way, this resource will be developed.”

The report’s trip was supported by a grant from the Institute for Journalism and Natural Resources.