Unlock Editor’s Digest for free

FT editor Roula Khalaf has chosen her favorite stories in this weekly newsletter.

With Christmas just days away, it’s a good time to reflect on the shopping season. I think a lot about the luxury retail market. This is because where the wealthy lead, the market, and even the economy as a whole, tends to follow. The past year has been the worst year for the luxury goods industry since the Great Recession of 2007-2009.

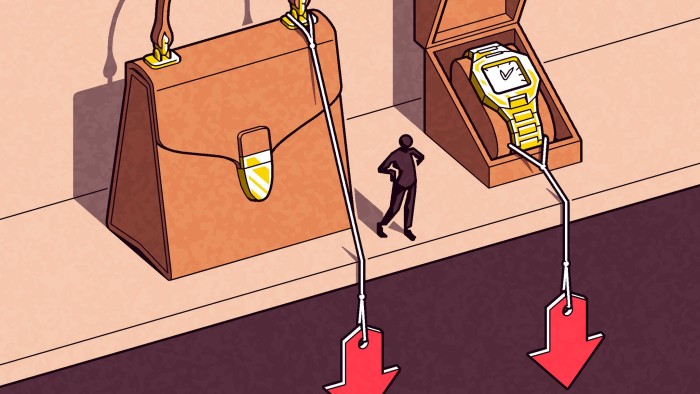

While the ultra-rich continue to consume as if they exist in a separate gravitational orbit, the aspirational consumers who make up the most important “mass luxury” part of the market are shrinking in size. This goes a long way toward explaining why many of the world’s largest luxury goods companies have underperformed recently. After all, there are only so many watches and handbags that 1% of people can afford.

And the number of people who can afford something like this is decreasing. According to Bain’s latest Luxury Market Report, released in November, the luxury market has shrunk by about 50 million consumers over the past two years, in part because younger consumers It’s about staying away from luxury goods. I think this is one of the reasons why we are (finally) seeing older people, especially older women, in advertising and fashion. They are the only ones who buy things.

But there are other reasons why luxury goods are losing their luster, the most notable of which is that despite a booming market, economic instability may be just around the corner. It’s a pervasive feeling.

Discounting the V-shaped drop caused by the coronavirus, the recession has been delayed by six years. Meanwhile, in the strange world of the U.S. stock market, which is priced for perfection, everyone at a New York dinner party is wondering when they intend to cash out at least some portion of their portfolio (and We are discussing whether or not it will become a reality.

Despite this, or perhaps because of it, the super-rich are still able to spend. The ultra-wealthy segment of the luxury goods market, the people who spend their spare cash on yachts and jets (both of which are doing very well), are seeing their net worths increase due to double-digit growth in the property market. The ultra-luxury cruise business has seen significant fleet expansion, and growth in luxury cars and hotels remains strong.

But the not-so-wealthy people who were once ready to splurge on that $500 handbag are becoming much more cautious. Because, unlike the super-rich, they still have to worry about working. According to Bain research, the disposable income of aspiring consumers is decreasing due to fewer job openings and higher voluntary turnover. As a result, overall luxury goods sales are expected to decline by about 2% in 2024 and remain flat next year.

So what does all this tell us about what will happen to the overall economy in 2025? There are three key lessons.

First, a correction in the US stock market will likely occur this year or next. But few wealthy people I’ve talked to doubt that it’s afoot. The fact that even the wealthy are cutting back on purchases of fine wine, jewelry, watches, and fine art shows that even if there is no full economic recovery, many wealthy consumers are likely to be affected by the economic slowdown and some form of market recovery. This means that adjustments are expected. The trade war has exploded.

Second, if the latter were to happen, Europe’s high-priced luxury goods sector would decline much faster and more violently than other sectors. Europe doesn’t have big tech companies, but it does have luxury conglomerates. Two of Europe’s top five companies by market capitalization are LVMH and Hermès.

If President Trump turns his critical eye to the continent, it is easy to imagine that products manufactured by these companies will be subject to tariffs. Remember when the EU imposed tariffs on motorcycles in retaliation for President Trump’s steel and aluminum tariffs, adding $2,200 to the price of a Harley-Davidson? European luxury brands, such as German automakers and French fashion brands, are likely to be politically chosen.

Finally, there is a growing recognition within the luxury goods industry that some of the price inflation seen over the past few years is simply unsustainable. Already, only the top brands in any category of personal luxury goods are able to maintain their price point as aspirational customers shift towards cheaper watches and spirits.

The same goes for travel and leisure. I recently spoke with two private equity investors in the U.S. hotel industry who said that while prime markets like Jackson Hole, Nantucket, and Martha’s Vineyard would probably survive a recession, I expected the room rates at a star hotel to be nosebleedingly high. The first signs of a market correction are likely to lead to a decline in the Houston market on Tuesday night.

This is welcome news for those of us who have noticed that $500 is the new $300 for hotel rooms in major American cities. But if you wait for interest rates to drop, you’ll always end up splurging a little on high-end beauty products.

The “lipstick index” is a term coined by beauty mogul Leonard Lauder that suggests a recession is imminent when the cost of purchasing small luxuries, such as new cosmetics, increases. In 2024, beauty was one of the few luxury categories to experience positive growth as consumers sought a little luxury.

If my husband is reading this, I’m hoping he has a tube of Celine Rouge Triomphe in his stocking.

rana.foroohar@ft.com