Few Oregonians ever see the high-tech work that drives the state’s economic motor.

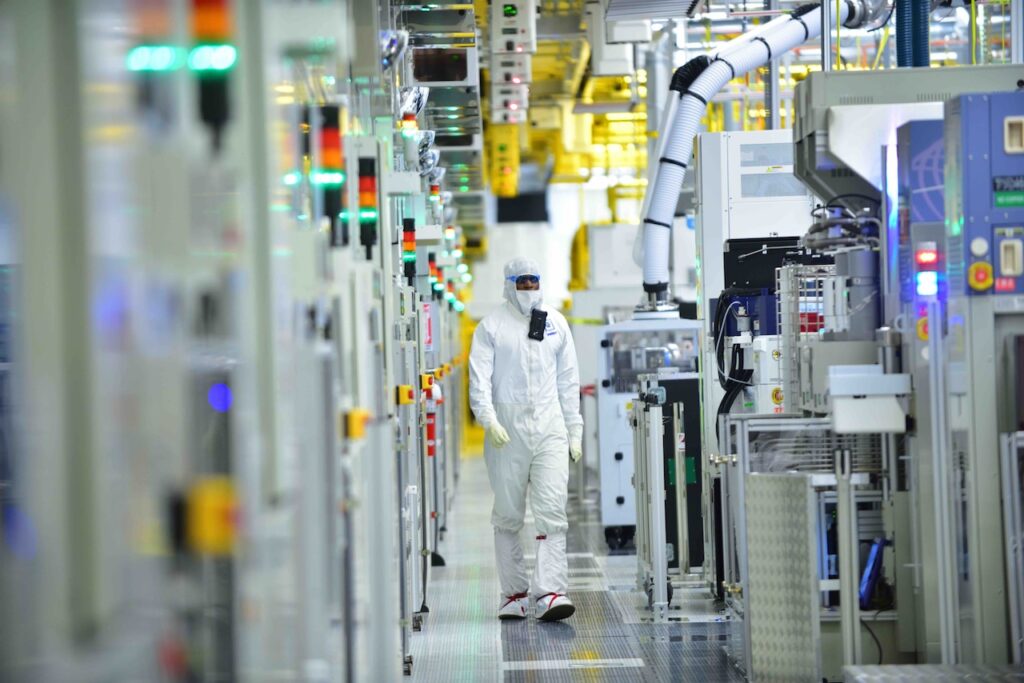

It takes place out of sight and mostly in secret, under fluorescent lights in Intel’s closely guarded Hillsboro cleanrooms. Technicians cloaked from head to toe in white bunny suits tend to enormous machines, manufacturing the microscopic circuitry that runs PCs and the internet itself.

This is the invisible work that has helped power the state’s economy since Intel arrived from Silicon Valley in 1976.

Today, Intel produces billions of dollars’ worth of computer chips in Oregon every year. Perhaps just as importantly, it spends billions locally to ready new generations of even more advanced semiconductors. The company employs more people than any other business in the state.

But Intel has fallen into disarray. Its sales are in decline, owing to technological blunders that go back a decade, and its leaders are desperately slashing costs. The chipmaker laid off 15,000 this fall, including 1,300 Oregonians, and eliminated many more jobs through buyouts.

Wall Street has all but given up on the company, driving down Intel’s share price by more than half this year. That dramatically shrinks the value of the stock bonuses that approximately 20,000 Oregon workers depend on for a key component of their pay.

The upheaval came to a head this week as the chipmaker’s board forced out CEO Pat Gelsinger, leaving uncertain his plan to spend billions restoring the company’s former glory.

The company hasn’t articulated a new plan, but industry observers say Intel has no good options.

With Gelsinger out, replaced by two executives elevated as interim co-CEOs, some expect the board will try to split the company, separating its manufacturing from its chip design work or possibly selling off some of the business.

Or maybe Intel will try to hold itself together and slowly rebuild, husbanding its cash while it awaits a technological or strategic breakthrough that could revive its fortunes.

Hillsboro remains the company’s main hub for researching and developing new technologies, but with sales down by a third since 2021, Intel has acknowledged it can’t afford to keep investing the way it used to. The company says it’s committed to continued Oregon expansion but won’t say when, or how.

“As with any site, the scope and pace of expansion will be based on business needs, market demand and responsible capital management,” the company said in a written statement this week.

Intel’s travails mean its next 10 years in Oregon will look very different from its previous five decades. Indeed, a diminished Intel will have severe consequences for Intel’s workers, the army of suppliers and contractors that help equip and maintain its factories, and for the state’s own future.

“That R&D investment in Oregon is at risk,” said Jim McGregor, a veteran semiconductor industry analyst who has tracked Intel for years. “That could be devastating.”

SPENDING SPREE

Intel is the largest player, by far, in one of the state’s largest industries.

Oregon exports more than $30 billion worth of electronics annually, most of which are semiconductors manufactured in Intel’s Hillsboro factories.

The state’s chip industry pays an average yearly wage of more than $150,000, according to government data, well over double the state average. Hefty pay from Intel is an especially big deal in Oregon, which relies on personal income taxes for the bulk of state revenue.

And Oregon has courted this work with local tax breaks now worth more than $200 million to Intel each year.

Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger abruptly retired this week. His turnaround plan called for Intel to spend its way out of a technology deficit. The plan failed because Intel’s sales fell sharply just as its capital costs soared.CQ-Roll Call, Inc via Getty Images

The Portland area has one of the nation’s densest concentrations of chip factories. Several smaller manufacturers operate in Intel’s wake, capitalizing on the pipeline of semiconductor industry suppliers and trained workers to make their own chips.

All that depends on Intel remaining a regional anchor, according to Frank Gill, a retired Intel executive.

“If some of that fades away with Intel, it’s going to make (Oregon) a less attractive place for other chip companies to come in,” he warned. That could put the state’s whole semiconductor ecosystem at risk.

Intel’s Oregon employees include top corporate executives, research scientists, marketers and finance professionals. Thousands of factory technicians in Hillsboro play essential roles in the company’s global manufacturing network and frequently step into its cleanrooms with just a two-year associate’s degree, offering lucrative careers to a diverse range of Oregonians.

Intel’s Hillsboro factories are among the most sophisticated in the world. Scientists and engineers peer years into the future to envision technology’s cutting edge and to enable continued advances in computing power.

They work with manufacturing tools that cost millions of dollars apiece — sometimes hundreds of millions.

Those high costs used to be a kind of advantage for Intel. Nearly all its rivals are smaller and couldn’t afford to keep up with Intel’s spending. It’s a strategy that made Intel, for many years, the world’s biggest chipmaker and a hugely profitable company with gross margins above 60%.

Now, though, Intel’s capital spending has become an albatross and the chipmaker is losing billions.

Modern chip companies fall into one of two camps — those that design computer chips and those that run the factories to produce them.

Chip designers are lean, efficient businesses like AMD and Nvidia with no factories of their own. They can move quickly to adopt new technologies for fast-growing markets like artificial intelligence.

Semiconductor manufacturing specialists are called foundries. There are only a handful of these in the world, and they must be continually refitted with the latest chipmaking technology.

The biggest is Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., a foundry that specializes in making chips for AMD, Nvidia and other chip designers. Foundries watch every penny and whatever costs they can’t contain they pass on to their clients.

Intel for decades found success in having it both ways, designing its own chips and manufacturing them itself.

That became a problem recently, though, because Intel hasn’t been doing either very well.

The chipmaker was slow to adopt new manufacturing technologies and fell behind TSMC in the race for the most advanced semiconductors. Intel itself now outsources some of its leading-edge chips to TSMC because they are too advanced for Intel’s own factories.

Meanwhile, Intel failed to anticipate the boom in demand for artificial intelligence and doesn’t have any chips that enable the most advanced AI computing.

When Intel hired Gelsinger nearly four years ago, he announced he would catch up to rivals by committing $100 billion to improve the company’s technology. Gelsinger would build new factories around the world, equipped with the most advanced production tools, to make Intel’s own chips and become a foundry for other chip designers.

The plan failed because Intel’s sales fell even as its spending soared.

The market for Intel’s PC chips sagged after a pandemic buying spree, and data center operators began buying semiconductors for artificial intelligence instead of Intel chips for conventional computing. Revenue plunged from nearly $80 billion in 2021 to around $50 billion this year.

IT TAKES TWO?

That puts Intel in a terrible bind.

The company’s depressed sales can’t support its ambitious spending. But if Intel doesn’t keep investing then it will lose the technological race.

“They have to be competitive with TSMC and Samsung. Otherwise, it doesn’t work, and the foundry, it will deteriorate over time,” said Dan Hutcheson, a veteran Intel observer at the research firm TechInsights.

One possible solution might be to split Intel in two, one side focused on chip design and the other on manufacturing.

That appears to be what the company’s board is contemplating. It promoted two Intel executives on Monday to become interim co-CEOs. That’s an unusual approach that seems to point toward the possibility that Intel will become two separate companies.

One of the new CEOs, a top Oregon executive named Michelle Johnston Holthaus, also became permanent CEO of a new organization within the company called Intel Products. It will focus on designing computer chips.

A divided Intel would have a profound impact in Oregon.

Current and former insiders, including some former executives, imagine Intel Products would take over Intel’s large Jones Farm campus near Hillsboro Airport.

The other company, Intel Foundry, might inherit Intel’s Gordon Moore Park manufacturing campus at Ronler Acres, five miles to the east.

Intel’s headquarters have always been in Silicon Valley, and most of its top executives still work there. But perhaps at least one of these two new companies might put its headquarters in Oregon.

PLAYING FOR TIME

If only it were that simple.

Intel’s factories are money losers, bleeding nearly $7 billion last year alone. The company says it will take three years before they turn profitable. Many observers believe it could take much longer.

Complicating matters, Intel Foundry has only one big client — Intel’s own chip design business.

If you split the two, the money-losing factory business couldn’t stand on its own without a commitment that the chip designers would continue sending most of their products back to Intel Foundry.

That could effectively tie Intel Products to a sinking ship and cancel out any benefits from splitting the businesses. Additionally, Intel agreed to restrictions on its ability to divide the company when it secured to $7.9 billion in federal subsidies last month.

Alternately, Intel might consider selling its business off in pieces. Or activist investors could step in, buying shares in the company and demanding its breakup.

That could be calamitous in Oregon, turning Intel’s huge local campuses into satellite operations of other companies that don’t need the full range of corporate and technological functions that have been the foundation of Intel’s Hillsboro sites for decades.

“The people who work at Intel have to be really panicked,” Hutcheson said.

Intel’s research factories in Hillsboro support high-volume production sites in Arizona, Ireland, Israel and — soon — in Ohio. If that manufacturing network were someday to break up, it’s not clear what role would be left for the company’s top engineers and scientists in Oregon.

After Congress passed the $52 billion federal CHIPS Act in 2022, Intel and Oregon officials campaigned loudly for the Biden administration to use some of that money on a major lithography research center in Hillsboro.

That $900 million project went to upstate New York, instead. Intel and Oregon remain hopeful of winning a packaging and prototyping research site from the CHIPS Act within the next two weeks, but the state’s prospects look increasingly tenuous as Intel’s position deteriorates and political turbulence roils Washington, D.C.

For all Intel’s problems, the chipmaker still has many things going for it, including the thousands of Oregon Ph.D.s who design and engineer its chips. Intel plans to introduce a new generation of semiconductor next year, called 18A, which it says will put it on even footing with TSMC technologically and could help attract new clients to its factory business.

Intel may also have time.

“I don’t think they’re desperate for cash. At least not right now,” said Stacy Rasgon, an investment analyst who follows the company for Bernstein Research.

That gives Intel a window to build its foundry business, prove its 18A technology and line up new clients to fill its factories. Rasgon thinks Intel is likely to divide the company eventually, provided it can deliver compelling manufacturing technology in the next year.

“A lot of this really hinges on 18A,” Rasgon said. “We won’t know this for a year, a year-and-a-half.”

So for now, Intel is in a delicate balance — nurturing its expensive technology ambitions while counting pennies.

It has permanently grounded the air shuttle that flew employees between its campuses on the West Coast, and it’s reduced the frequency and duration of workers’ cherished sabbaticals.

Intel shelved plans for new factories in Germany, Israel and Poland while delaying the opening of new factories in Ohio. Intel says it plans to keep investing billions in its Oregon factories, but the big-ticket item, a fourth phase to its D1X research factory in Hillsboro disclosed last year, appears in limbo.

In addition to the billions in federal subsidies, Intel is in line for $115 million in Oregon taxpayer money to fund Hillsboro expansion. To get the full amount, Intel promised to hire nearly 1,700 new workers plus grow total employment by another 900 jobs through contractors and construction workers.

That would require a major reversal of this fall’s layoffs. Intel said this week it still plans to follow through on the expansion plans described in its agreement with the state.

“We remain committed and look forward to delivering on the shared vision it represents,” the company said in a statement.

For now, Intel and its remaining employees are left trying to do more with less. Rasgon said that’s the paradox Intel must somehow overcome, finding a way to continue innovating while containing costs and cutting jobs.

“My LinkedIn feed is just full of 30-year Intel lifers that are leaving now. Aren’t those the folks you want to keep? There’s all that knowledge walking out the door,” Rasgon said. “I don’t know how the layoffs make you more competitive.”

— Mike Rogoway covers Oregon technology and the state economy. Reach him at mrogoway@oregonian.com or 503-294-7699.

Our journalism needs your support. Please become a subscriber today at OregonLive.com/subscribe