Getty Images

Getty ImagesSouth Korean parliamentarians narrowly failed to impeach the president after briefly trying to declare martial law.

The bill censuring Yoon Seok-yeol fell three votes short of the 200 needed to pass, and many members of the ruling People’s Power Party (PPP) boycotted the vote.

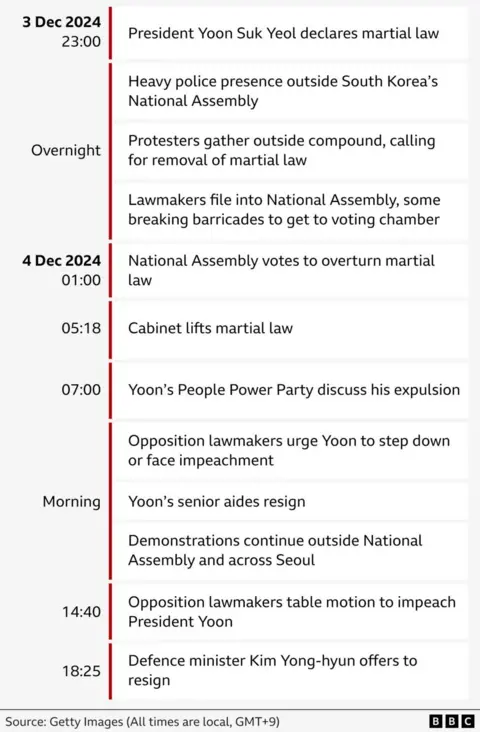

South Korea’s prime minister on Tuesday declared a military regime linked to authoritarianism in the country in a bid to break a political impasse, sparking widespread shock and anger.

Yun’s declaration was quickly overturned by parliament, but hours later the government rescinded it amid mass protests.

Passing an impeachment bill requires a two-thirds majority in the National Assembly, meaning at least eight PPP members must vote in favor.

However, all but three walked out of the chamber early Saturday.

One of those who remained, Cho Kyung-tae, admitted that Yoon’s apology for martial law on Saturday morning, after he disappeared from public view for three days, influenced his decision not to support impeachment this time. .

“The president’s apology and willingness to resign early, and to delegate all political tasks to his party, influenced my decision,” he told the BBC before the vote.

Cho said he believed impeachment would transfer the presidency to Lee Jae-myung, leader of the Democratic Party of Korea (DPK).

He said Yun’s “irrational and absurd decision” to impose martial law “cast a shadow over what he described as the many extreme actions” of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea during his time in power. ” he added.

Lee Eun-joo, a lawmaker from the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, told the BBC that she cried when the PPP politician walked out.

“We knew they might boycott the vote, but we didn’t think they would actually boycott the vote with tens of thousands of people watching right outside,” she said. .

After Saturday’s vote, Lee insisted his party would “not give up” on impeaching Yoon, who posed the “worst risk” to South Korea.

“We will definitely return this country to normalcy by Christmas and the end of the year,” he told a crowd gathered outside the National Assembly in the capital Seoul.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBefore Tuesday, South Korea had not been under martial law (temporary military rule during a state of emergency, usually restricting civil rights) since before it became a parliamentary democracy in 1987. .

Yun argued that measures were needed to defeat “anti-national forces” in Congress, and mentioned North Korea.

However, the move comes after the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea won a landslide victory in April, following political deadlock and scandals surrounding the main party, which led to the party vetoing passed legislation. Some saw it as an extreme reaction to Teyun’s growing unpopularity. Lady.

The president’s late-night speech sparked dramatic scenes in parliament, with demonstrators descending en masse as military personnel tried to block them from entering the building.

Lawmakers scuffled with soldiers, and 190 MPs entered the building to reject the order.

Early Wednesday morning, the Yun Cabinet lifted martial law.

However, the military occupation was short-lived, with daily protests taking place in the streets. Some people supported Yun, but they were drowned out by the angry mob.

Authorities later revealed more details about Tuesday night’s events.

The commander charged with military occupation said he learned about the decree along with everyone else in the country on television.

He said he refused to allow the military to arrest lawmakers inside parliament and did not give them live ammunition.

The National Intelligence Service later confirmed rumors that Yoon had ordered the arrest and interrogation of some of his political opponents, including his own party leader Han Dong-hoon.

Following these revelations, some members of Yun’s own party expressed support for impeachment.

The president’s apology on Saturday morning appears to be a last-ditch effort to shore up support.

He said the declaration of martial law was made out of “despair” and vowed not to impose martial law.

Yun did not offer to resign, but said he would leave it to the party to decide how to stabilize the country.

If he were to be impeached, it would not be unheard of. In 2016, then-President Park Geun-hye was impeached for aiding and abetting a friend’s blackmail.

If the South Korean parliament passes the impeachment bill, a trial will be held by the Constitutional Court. A two-thirds majority of the court would need to support his permanent removal from office.

Additional reporting by David Orr, Gene McKenzie and Tiffany Turnbull