Marisa Wojcik:

Has anything changed in the way you think about your work, the way you work, the way you think about people’s behavior…

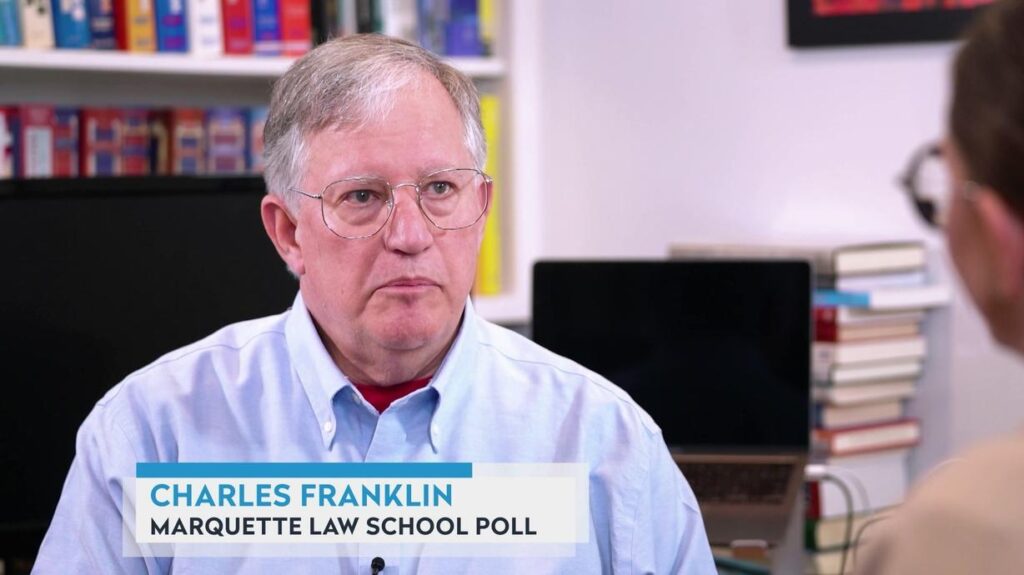

Charles Franklin:

Yeah.

Marisa Wojcik:

…Generally over time or just recently?

Charles Franklin:

I think in recent years there has been a shift in campaigns, state-level and national-level debates to less policy-focused. The campaign certainly reflects the group’s interests, but maybe I’m a bit of a policy picky. I’d like to hear about your economic plans and the details of your public health plans or your foreign policy plans. And I think over the past 12 years, for example, since we started doing market polling, we’ve seen campaigns become a little less policy focused and more looking for broader images and impressions. We can give you a sense of what our policies are, but they’re not. You are expected to define those policies in all kinds of detail. And ironically, with this year’s Project 2025, we’re starting to see why the campaign doesn’t want that. Because Project 2025 has 900 pages of detailed plans written down. Some people may love it, some may hate it, but they are specific proposals, and Donald Trump denies any association with them. This shows kind of the danger of being too specific about what you’re trying to do. I don’t think the Harris campaign is very specific about the details yet, and the Trump campaign isn’t very specific about the details either. I think that’s the difference from 2012 and 2008. It’s not that we’ve always published white papers with a high sense of purpose for our campaigns, but I think we’ve moved a little bit more towards emotions and impressions and general sentiments, discussions about issues, and serious There are not many serious discussions about this issue.

Marisa Wojcik:

What do you think is the reason?

Charles Franklin:

I think it’s more about electoral self-interest than anything else. Project 2025 shows you the downside of being too specific. I also think that the polarization of electoral districts has increased, and it has become commonplace for 95% of Republicans to vote for the Republican Party and 95% for Democrats to vote for the Democratic Party. This is a far cry from the days when people could go to the polls on the same election day and win big majorities for Tommy Thompson and Herb Cole. I don’t go over it much anymore. We don’t give much consideration to the other side’s attractive arguments. There’s a reason for that. As the parties have become more fragmented, there is less common ground between which voters can choose. Since the early 2000s, instead of trying to win the support of centrists, political parties have mobilized their base of voters, the most powerful and committed voters, and maximized their turnout. There has been an increasing emphasis on And the logic is pretty convincing. If you can get one of your core supporters to vote for you, you are virtually guaranteed to get that vote. But even if you succeed in getting independents to vote for you, you might only have a 60% chance of getting them. And the power of this logic is that campaigns become more focused on their base of support and, to some extent, do less to attract as many people as they once did. That’s more persuasive.

Marisa Wojcik:

Does that explain Tammy Baldwin and Ron Johnson?

Charles Franklin:

I think that’s true to some extent. Baldwin is particularly notable for campaigning in areas of the state where Democrats typically don’t win, such as rural parts of the state, but again, Democrats haven’t done very well, which has paid off for her. Ta. She may or may not win in these areas, but the margin she loses is much smaller, and that helps her win statewide. Ron Johnson fell behind in the race in both 2016 and 2022, with his favorability numbers flipping and being more unfavorable than favorable, but steadily gaining support in both campaigns. I think that’s an interesting example of a candidate. Through the election campaign, he ended up winning a small victory in 2016 and a small victory in 2022. So I think both of these campaigns from these different political viewpoints have not succeeded in sweeping the centrists, but succeeded in doing well in the centrists. to continue their campaign.

Marisa Wojcik:

What else would you like to take home?

Charles Franklin:

I think the bigger long-term issue is a decline in citizen participation, trust in government, trust in the political process, and this is nothing new. This number has been worsening since the 1960s and will continue to worsen. As a result, a significant portion of the population is highly skeptical of government, skeptical of its ability to improve the situation, and has great distrust of political actors. That includes the media, pollsters, and other places you may have visited for information you believe to be reliable. This situation has worsened considerably over the past 30-40 years, and has worsened even more over the past 10 years. I think that’s one of the mechanisms that not only makes politics more brutal, but also makes it more difficult for us to find solutions to problems. There are many problems in which a little old-fashioned bargaining between the parties could at least address some elements of such disagreements, but we have entered an era in which such bargaining is rare. It seems like it is.